Today is the 40th anniversary of the publication of my first attack on the Postal Service. “Time to Stamp Out the Postal Monopoly” was the lead article on the Boston Globe oped page . A dozen years later, the chief postmaster of Boston denounced me as “the nation’s number one postal basher.”

I forgot to thank the postal unions for clinching the 1978 sale of that piece – my first in a major paper. I had pitched the piece to the Globe a couple months earlier and revised it to their specifications. But then I heard nothing and I assumed the piece was dead. Then the postal unions threatened a nationwide strike, kindly providing a newspeg (and perhaps also enraging some Globe editors). The Carter administration placated the unions with hefty raises and guaranteed lifetime jobs.

Back in those days, the U.S. mail was practically the only way an aspiring writer could afflict editors in distant cities with his work. Stamp prices were skyrocketing and service was wildly erratic, delaying the arrival of vital reject slips. Mail delivery ceased entirely for a week after the postman became frightened of the Dobermans owned by the drug dealers on the ground floor of the rickety apartment building where I lived. To visit a Boston post office was to descend into a netherworld of zombies and psychopaths who hated anyone who approached them with an unstamped envelope. The worst outrage was that it was a federal crime for anyone else to provide better mail service.

The next year, I whacked the Postal Service in the Washington Star and followed up, after I moved to the Midwest, with a hit in the Chicago Tribune in 1980. That piece led to my first talk show – an appearance on Chicago’s WVON radio station. It did not occur to me that I should be conversational instead of responding warily, like I was being cross-examined late at night at a police road block. The talk show host utterly misunderstood the article and her questions seemed inane. When I asked her to clarify, she repeated her lines louder. I was unaware that interview questions are often written by an assistant or an intern. For a talk show host to read an entire 700-word article is like a normal person reading Moby Dick.

After I moved to Washington, I often visited the lavish new headquarters of the Postal Service – thanks to their top floor library with panoramic views and a nook where stogies could be puffed all day. Old histories and dog-eared reports proved that the Post Office had been warring against its competitors ever since Congress gave it a monopoly over letter delivery prior to the Civil War. I burst out laughing when I to read the Post Office’s 1960 annual report’s proclamation of “the ultimate objective of next-day delivery of first-class mail anywhere in the United States.”

I smacked the Postal Service in publications ranging from Inquiry to the Los Angeles Herald Examiner to the Washington Times. Beginning in 1984, I regularly slammed the Postal Service in the Wall Street Journal, whose editorial features editor Tim Ferguson was the best and stoutest libertarian-leaning editor I encountered at a major outlet. I hammered the theme that “mail service is becoming slower, more expensive and less reliable.” I also pointed out how the Postal Service’s delivery tests – endlessly touted in their advertisements – were utterly fraudulent.

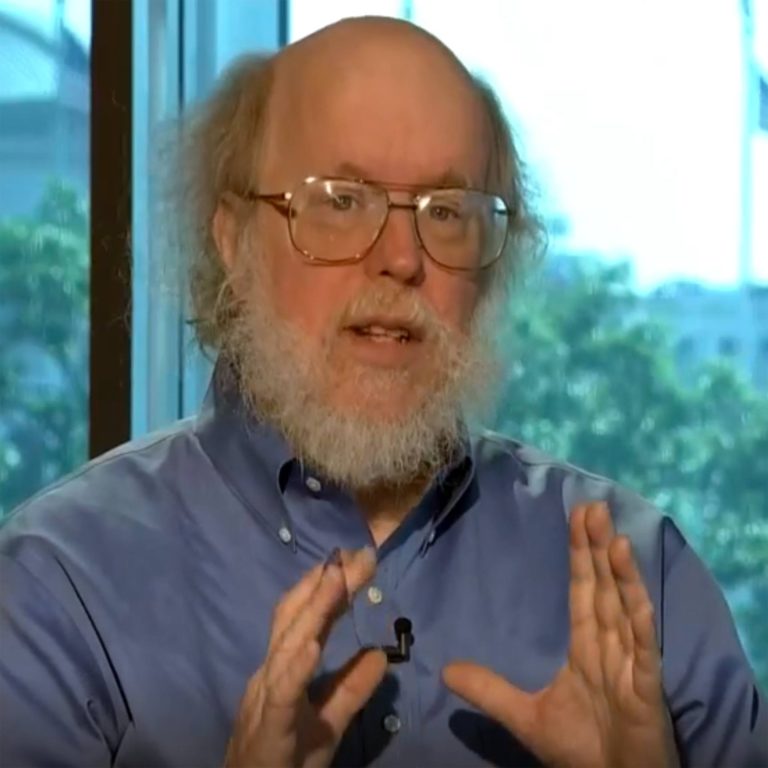

Every time the Postal Service raised postage rates or slashed service, I gave them another wallop. In a 1987 New York Times op-ed, I wrote that “First-class mail is becoming the ghetto of American communications… The U.S. cannot afford to enter the next century with a communications system little changed from the 18th century.” Assistant Postmaster General Frank Johnson responded that “Bovard continues to play his fanciful intellectual demolition derby… He often allows his bandwagon to run amok, rolling over much that is good. Pedestrian facts end up flattened.” Earlier in 1987, Johnson complained to the Wall Street Journal that I was “the Pied Piper of Privatization.”

Mauling the mail service led to my first gig as a scarecrow. The National Association of Postmasters invited me to speak to their annual Washington conference so that members would have “a clear picture of the very real threats that are bombarding us daily,” the association’s chief, a grizzled Irish postmaster-politician from Massachusetts, declared. I ambled up to the lectern at 9 a.m. Five minutes later, I had all 300 audience members on their feet howling with homicidal intent.

I spoke about how government monopolies lacked incentives to provide good service and asked: “If you had to invest your life savings in one company – would you choose United Parcel Service or the Postal Service?” “We already invested our lives in the Postal Service!” came the thunderous response. Oops.

The Boss Postmaster repeatedly jumped on stage to simmer the audience down so I could finish. Afterwards, he unleashed a podium-pounding tirade that flailed my views up-and-down and strutted before his members as if he’d just slain an anti-postal dragon. I only wish I could pocket $500 every time I get heartily cussed.

In 1989, nudged by Tim Ferguson, I spent five months seeking an interview with Postmaster General Anthony Frank. But a Postal Service spokesman told me that since the Postmaster General had recently appeared on “The Pat Sajak Show,” he did not need exposure in the Wall Street Journal. Besides, the spokesman said, my previous postal articles had been “tainted with bias.” Though the Postal Service was losing $2 billion a year, Frank scorned fundamental reforms, claiming that privatization would be “the Wino and Derelict Full Employment Act…. A lot of [the private carriers] would only work until they get the price of a bottle of Ripple and then they’d quit.” I scoffed in a WSJ piece that “the American people no longer need a monopoly that appears more interested in storing letters than in delivering them.” In a reply to the Journal, Frank complained that the piece was “just another case of Mr. Bovard mixing facts with fancy to suit his own” agenda.

In a 1991 Wall Street Journal piece, I jibed that “the Postal Service is the only delivery business that believes speed is irrelevant” and said that a pending four-cent hike in stamp prices “will help finance the greatest intentional mail slowdown in U.S. history.”

After I smacked the postal monopoly in USA Today in 1995, the Postal Service’s “media relations” manager claimed it was “utter nonsense” that the Postal Service was intentionally slowing the mail and lamented: “We find it very frustrating when individuals with an agenda and a pen are given a forum to spread malicious misinformation.” Since then, the Postal Service has become far more forthright about its slowdowns – which never produce the savings anticipated. But since they have captive customers, why not abuse them?

The Postal Service has a long history as a tool of government surveillance and suppression. Writing in USA Today in 1999, I hammered the Postal Service’s crackdown on private mail boxes and touted corrective legislation championed by Rep. Ron Paul. That piece concluded that “the only real solution is to demilitarize the Postal Service’s legal arsenal and end its power over other businesses and American citizens.”

In 2011, after the Postal Service announced plans to largely abolish overnight mail delivery, I slammed them in the Los Angeles Times: “When people bought ‘forever’ stamps, they didn’t realize that the name referred to the delivery time, not stamp prices.” The Times published a letter from an angry postal fan who demanded to know: “Was James Bovard bit by a mailman as a child?”

In 2013, the Justice Department and Postal Service filed suit against Lance Armstrong’s bike racing team (which received $40 million from the Postal Service), claiming that Armstrong had conspired to defraud the feds by using illegal stimulants. I commented in the Washington Times that “that conspiracy charge sounded like a good summary of the Postal Service’s own public relations strategy.” Besides, it made “no sense to to bankroll a bicycle-racing team at the same time that postal employees were widely perceived as a bunch of slackers.”

At this point, the Postal Service is rapidly becoming little more than an income maintenance program for the 630,000 employees. The big question is which will reach zero first – mail delivery targets or the Postal Service’s actual performance. Either way, the Postal Service continues to provide some of the starkest and most comical reminders of the folly of relying on the government.