Tuesday, March 25, 2008

The Rights and Wrongs of Reverend Wright

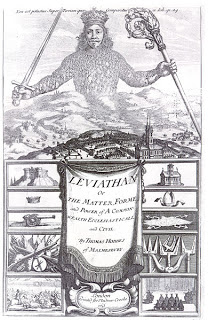

“There is a purely civil profession of faith of which the sovereign should fix the articles, not exactly as religious dogmas, but as social sentiments without which a man cannot be a good citizen or a faithful subject.

While it can compel no one to believe them, it can banish from the state whoever does not believe them — it can banish him, not for impiety, but as an anti-social being, incapable of truly loving the laws and justice, and of sacrificing, at need, his life to his duty. If any one, after publicly recognizing these dogmas, behaves as if he does not believe them, let him be punished to death: he has committed the worst of all crimes, that of lying before the law.” The loathsome Jean-Jacques Rousseau, explaining his totalitarian concept of the “Civil Religion” in his tract The Social Contract. The “Weeping Prophet,” as envisioned by Michelangelo: The Renaissance master’s rendering of the Prophet Jeremiah, as found on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel.

The “Weeping Prophet,” as envisioned by Michelangelo: The Renaissance master’s rendering of the Prophet Jeremiah, as found on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel.

Jeremiah was a defeatist.

No, I’m not referring to Rev. Jeremiah A. Wright, the much-execrated former Pastor of Chicago’s Trinity United Church of Christ. I’m referring to the Hebrew prophet for whom Rev. Wright was named.

For about a quarter-century, Jeremiah made himself notorious in Jerusalem for loudly and unapologetically denouncing its religious and civic corruption: “… from the least of them even to the greatest of them, Everyone is given to covetousness; And from the prophet even to the priest, Everyone deals falsely.” (Jer. 6:13, NKJV).

The City’s inhabitants had come to trust entirely “in lying words that cannot profit.” Those were seductive deceptions, all the more alluring because they were clothed in diaphanous robes of piety, giving them license to “steal, murder, commit adultery, swear falsely,” commit idolatry of various kinds, and then take comfort in the conceit that they were God’s Chosen People in His Chosen City. Yet Jeremiah’s prophetic message was one of irrepressible divine judgment, with the Lord repeatedly posing the rhetorical question, “Shall not my soul be avenged on such a nation as this?” (See 5:9, 5:29, 9:9).

Not content merely to speak the message he had been given, Jeremiah chose to act it out as well, walking through the streets of Jerusalem wearing a yoke to symbolize the impending conquest of the City by Babylon and subsequent captivity.

This did nothing to enhance Jeremiah’s social standing, of course. (See 20:7-10.) He suffered relentless ridicule, arrest, and mistreatment of various kinds, such as being imprisoned in a miry pit.

But this is only to be expected: Shouldn’t Jeremiah have knelt in abject gratitude every day for the singular blessing of being born in the greatest community in the world? Why couldn’t he find something positive to say about the Holy City and its inspired rulers? How dare he undermine civic morale, thereby emboldening Jerusalem’s implacable enemies!

Tangible evidence of Jeremiah’s historicity: This clay tablet, dated to around 595 B.C., makes reference to an obscure Babylonian official mentioned in Jeremiah 39:3.

After the first Babylonian assault on the City, Jeremiah was thrown in prison as punishment for his “defeatist” talk — specifically, his prophecy that the Babylonians would come back and finish the job.

He was still imprisoned when that prophesy was fulfilled. The Babylonians freed him, and some traditions claim that Jeremiah wound up in Egypt, where he was murdered in his dotage by former fellow citizens of Jerusalem who had never forgiven him for bearing prophetic witness against the City’s evils.

What got Jeremiah killed — if the tradition adverted to above is true — was his disdain for Jerusalem’s Civil Religion. His anti-social insistence on telling the truth, as God inspired him to understand it, about the evil of the government that ruled him, and the people who sustained that government and permitted it to lead them to destruction, was what provoked people to kill him.

Rev. Jeremiah Wright has on occasion displayed a gift for anti-social truth-telling. His notorious and much-misrepresented post-9/11 sermon did not minimize the horror inflicted on our nation that day, or the blood guilt of those responsible for the atrocities.

Speaking with commendable courage and mesmerizing passion, Wright described the long train of abuses and outrages committed by the government that rules us — from the Trail of Tears through Hiroshima and Nagasaki, from Wounded Knee to the first Gulf War — and asserted that the criminal violence of our rulers did much to sow and nourish what we harvested on that terrible Tuesday morning.

These were unwelcome but indispensable truths spoken in a timely fashion. That having been said, it must not be thought that Rev. Wright is a prophetic figure.

Wright’s creed, to the extent I can understand it on the basis of broad but not particularly deep research, is an Afro-centric variation of the socialist heresy called Liberation Theology. Wright’s chief theological influence is James Cone of the Union Theological Seminary.

A sense of Dr. Cone’s doctrine can be found in the following widely quoted statement:

“Black theology refuses to accept a God who is not identified totally with the goals of the black community. If God is not for us and against white people, then he is a murderer, and we had better kill him. The task of black theology is to kill Gods who do not belong to the black community … Black theology will accept only the love of God which participates in the destruction of the white enemy. What we need is the divine love as expressed in Black Power, which is the power of black people to destroy their oppressors here and now by any means at their disposal. Unless God is participating in this holy activity, we must reject his love.”

Cone’s theology is actually a form of idolatry: He insists on creating a “God” to suit his personal specifications, which in this case would be a variant of the Golem myth — a monster summoned to smite and destroy an enemy. It is a photographic negative of the neo-Nazi “Aryan Christ” heresy.

More importantly, Cone’s version of idolatry is unmistakably akin to every other version of the Civil Religion — that is, a theology that supports concentration of power in a political state and the punishment, through ostracism, banishment, or liquidation, of those who refuse to make the State the cynosure of their existence.

Wright’s denomination, the United Church of Christ, is unmistakably a hyper-liberal outgrowth of the late-19th Century “social gospel” movement, which was inspired in large measure by Hegel’s appropriation of Rousseau’s Civil Religion concept. What is not widely understood is that the contemporary “Christian Right” shares the same pedigree, a fact amply documented in Richard M. Gamble’s compulsively readable — and entirely indispensable — book The War for Righteousness: Progressive Christianity, the Great War, and the Rise of the Messianic Nation.

Both strands of “progressive” Christianity, whether they admit it or not, view the State as an instrument through which divine ends can be achieved through the skillful and pious use of lethal force. “Left” progressives extol the supposed virtues of wealth redistribution and various policies intended to cure people of prejudice through state terror. “Right” progressives condemn wealth redistribution, preferring to promote punitive policies regarding various forms of personal immorality and the holy wholesale slaughter of non-Israeli foreigners.

The strands can be traced back to the reign of Woodrow Wilson, during which the State was unleashed, with the clergy’s enthusiastic approval, on both the foreign and domestic fronts.

As I’ve noted before, the gospel of the Total State, as translated into the idiom of American Christianity, has rarely if ever been stated as bluntly as it was by William P. Merrill in this couplet published in the April 26, 1917 issue of Christian Century (just weeks after war was declared on Germany):

The strength of the State we’ll lavish on more, Than making of wealth and making of war; We are learning at last, though the lesson comes late, That the making of man is the task of the State.

Difficult though it might be for some to understand, there was a time when doctrinally orthodox and socially conservative American Christian clergymen wanted nothing to do with statist sentiments of that variety, even — no, especially — when they took on a nationalist tenor.

One very suitable example was offered by Rev. Clarence Waldron of the First Baptist Church in Windsor, Vermont. Mildly Pentecostal in his worship style, Waldron was entirely conservative in his theology and moral views. He was also insurmountably opposed to American involvement in World War I.

In October 1917, Wilson, acting as Pontifex Maximus of the American Civil Religion, urged churches across the nation to decorate their sanctuaries in Red, White and Blue on the twenty-first and lead their congregations in singing “The Star-Spangled Banner.” Then a collection was to be taken up as part of “Liberty Loan Sunday,” with the mulcted proceeds to be sent as war tribute to Washington.

Waldron refused to play along. When the twenty-first arrived, he preached a gospel message in a chapel blessedly bereft of jingoistic adornments. As Vermont historian Mark Bushnell recalls,

after the service a mob descended on Waldron in front of the church and forced the pastor to wrap himself in the flag and sing the National Anthem.

Shortly thereafter, Waldron was removed as pastor, in large measure because of suspicions about his “loyalty” — not his loyalty to Christ, or his fidelity to Christian precepts, mind you, but his loyalty to the “god” revered by adherents of the Social Gospel — the American State.

In December 1917, Waldron was indicted by a federal grand jury indicted for violating the Espionage Act. Passed the previous June, that measure imposed prison terms of up to 20 years for any act or statement perceived as willfully obstructing “the recruiting or enlistment service of the U.S.”

The specification against Waldron was that “he had once been heard to say ‘to hell with patriotism.'” To his undying credit, Waldron admitted on the stand that he had said those words — in condemnation of the cultish “Gott mitt uns” nationalism promoted by Kaiser Wilhelm’s regime in Germany.

“If this is patriotism,” a disgusted Waldron had told his acquaintances, “to hell with patriotism.”

Apparently, it was a crime and a sin in Wilson’s America to impugn nationalism of any variety:

Waldron was convicted and sentenced to 15 years in prison, eventually serving a little more than a year. Of the roughly 1,000 Americans convicted under the World War I Espionage and Sedition Acts, Waldron was the first to be imprisoned exclusively for his religious beliefs.

Rev. Waldron’s “crime” was essentially the same as Rev. Wright’s offense, and I suppose the fact that Wright has not yet been forced to undergo prolonged public humiliation and imprisonment means that our nation hasn’t sunk into the abyss of collective dementia that claimed the liberty of so many during World War I.

Yet.

What I find most interesting about the manufactured controversy about Wright is this: Nearly all of the commentary generated about Wright’s sermons focuses on the racial aspect of his theology, rather than examining the merits of his critique of the warfare state. Even Obama’s widely praised speech about his decades-long relationship with Wright focused chiefly on issues of race relations, while either ignoring or condemning Wright’s principled critique of Washington’s wars and foreign policy.

Clearly, there are people who seek to exploit, for consummately cynical reasons, lingering inter-ethnic tensions (Michelle Obama, an attorney who specializes in “diversity consulting,” could be considered a profiteer of sorts in this respect). Republican herd-poisoners are already preparing to depict Obama and Wright as closer than Damon and Pythias, and on previous experience I don’t think many of the GOP’s campaign flacks care whether or not that characterization is true.

Amid all of this, it’s important to remember one vital fact: What prompted the ritual denunciation of Wright (including an artfully parsed one by Sen. Obama) was not his congregation’s aberrant race-centered theology or even his own intemperate remarks on that subject. Rather, it was his blasphemy against the Civil Religion and the endless good works done in its name — bombings, invasions, official liaisons with dictators, all of that good and righteous stuff. That kind of “sin,” as Rousseau warned centuries ago, simply can’t be forgiven.

Dum spiro, pugno!

Content retrieved from: http://freedominourtime.blogspot.com/2008/03/rights-and-wrongs-of-reverend-wright.html.