Sunday, May 4, 2008

An American Gulag

Sixty years ago a young American named Alexander Dolgun was accosted on the streets of Moscow by a couple of affable fellows working for the Soviet secret police (known at the time as the MGB).

Assuming he was the victim of mistaken identity or some innocent bureaucratic bungle, Dolgun — who worked as a file clerk at the U.S. Embassy — offered neither resistance nor objection when he was taken to the Lubyanka Square headquarters of the secret police.

It was only after he was forced to surrender his personal belongings and taken for interrogation that Dolgun realized that he was not being questioned as a witness or criminal suspect, but rather being detained for summary punishment as a political criminal. Sidorov, his chief interrogator, explained that Dolgun stood accused of espionage and terrorism under Article 58 of the Soviet penal code.

The 22-year-old Dolgun would spend the next eight years in Soviet prisons. His first 18 months were spent in prolonged torture and interrogation at Lubyanka and Lefortovo before being given a 25-year-sentence in the Gulag. Before being sent to the camps, Dolgun was repeatedly beaten, starved, subjected to engineered extremes of temperature, denied rudimentary necessities of hygiene and self-maintenance, and subjected to random but malicious noise as a way of undermining his mental stability.

Of all the privations and torments he was forced to endure, none of Dolgun’s afflictions could compare to prolonged sleep deprivation. When he was in his cell, he was permitted to sit or stand, but never to sleep, between 6:00 a.m. and 10:00 PM. And he was subjected to lengthy and brutally tedious interrogations every night, leaving him with only an hour or so to sleep for every circadian cycle.

“Try to go without water for a whole day,” Dolgun invited in his memoir, An American in the Gulag. “Then imagine that your thirst is a desire to sleep. Then you will have ten percent of what I felt” as weeks and then months of accumulated sleep deprivation took its toll.

“Stop breathing as you read this page,” he continued. “See how long you can keep from taking a breath. See how desperate you begin to feel as your heart begins to pump hard and your forehead begins to feel strange. Now, still not breathing, imagine there is no air left in the room. The muscles around your chin and neck are straining. Your larynx begins to make involuntary sounds and the bottom of your rib cage hurts. If you are really disciplined and carry this quite far, your vision will begin to blur.”

“That is how badly I wanted sleep,” Dolgun explained.

Dolgun, of course, had done nothing. But that didn’t stop the Soviet regime’s homeland security apparatus from interrogating, torturing, and imprisoning him. Indeed, it was because Dolgun refused to admit to acts he hadn’t committed, despite the depraved ingenuity of the world’s most cunning torturers, that he had to remain in prison for at least a little while; otherwise, the State

would suffer a loss of prestige.

At one point, driven to a frenzy of violence by Dolgun’s quiet but persistent refusal to admit espionage activities of any kind, Sidorov flew into a spittle-flinging paroxysm of rage, beating the American and threatening to kill him and track down his family. Seeking to bend the recalcitrant American to the State’s will, Sidorov put the matter in the most elementary terms imaginable:

“The State f***s you, you stupid son of a bitch!”

An innocent man: Murat Kurnaz (left), seen here as a teenager with his younger brother Alper.

If that specific phrase was ever directed at Murat Kurnaz during his five years in U.S. military custody, the young man is too decorous to admit it. Kurnaz, a Turkish national and legal resident of Germany, was sold into the hands of torturers for $3,000 by Pakistani bounty hunters in late 2001. He was detained in a former Soviet military base in Afghanistan before being transferred to Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. His tormentors wore the uniforms of the United States Armed Forces, and the treatment inflicted on him as an “unlawful enemy combatant” were nearly identical to the torture methods applied to Dolgun by the Soviet secret police.

Kurnaz was 20 at the time he was delivered into the clutches of the world’s most powerful criminal apparatus, the Untied States Government. He had been a bouncer and bodybuilder back in Germany, but only recently had developed an interest in his Muslim faith. As with so many spiritually unfocused men his age, Kurnaz’s sudden interest in his inherited faith was piqued by a pious young lady, Fatima, whom he intended to marry.

According to his memoir, Five Years of My Life: An Innocent Man in Guantanamo, it was Kurnaz’s desire to be a suitable husband that prompted him to go to Pakistan in search of appropriate religious training,. Unfortunately, this happened at the worst possible time — just weeks after 9/11. Compounding his misfortune was his mother’s concerns, expressed to German officials in Bremen, over her teenage son’s recent interest in religion, and his decision to grow a beard.

Just days after the U.S.-led war in Afghanistan began, Kurnaz was dragged off a bus by Pakistani officials and taken into custody. A couple of weeks later, as the officer who supervised his captivity pleaded “mecburi, mecburi” (“forgive me” in Turkish), Kurnaz was bound, had a sack pulled over his head, and taken to a nearby airport where he was surrendered to the U.S. military.

Bear in mind, that Kurnaz had been confined for about two weeks in Pakistan, a regime not noted for its delicacy, and had been interrogated by Turkish officials, who likewise represented a government not renowned for its solicitude toward prisoners. But it wasn’t until he was in the hands of Americans that he was mistreated.

Trussed like a slaughtered deer, shrouded in darkness because of the blacked-out goggles, Kurnaz was thrown roughly into a military combat plane with numerous other detainees. He was utterly helpless and completely disoriented, but this didn’t stop the valiant heroes supervising his delivery from inflicting needless injury on him:

“`Sit!’ a GI screamed in my ear,” he recalls. `Sit! Sit down, motherf****r!’ I fell on my behind and cowered on the metal floor. The soldier pressed my head down…. Suddenly I felt a blow to my head. I fell over to one side and lay there. Then I received a kick to the stomach. It was the first time I was beaten. They kicked my arms, legs, and back with their boots. I had no way of defending myself. All I could do was cower.”

Once Kurnaz and the others arrived in Afghanistan, the abuse continued:

“They never let up hitting, kicking, and insulting us…. `You’re terrorists,’ they shouted. `We’re Americans! We’ve got you! We’re strong! And we will give it to you!'”

Or, as the Soviet torturer Sidorov said to his American victim: The State f***s you.

Amazingly, Kurnaz was somewhat understanding of the treatment he received at the hands of American soldiers, just as Alexander Dolgun was initially understanding toward his Soviet captors:

“The soldiers had to assume I was a terrorist, if that’s what they had been told. If that was true, they had good reason to beat me. Although it was unjust, I could understand them.”

This equanimity was a by-product of Kurnaz’s misplaced hope that his innocence would be quickly established, and he would soon be free to return to his family. That optimism was gravely wounded, but not quite killed, by the first interrogation session, in which he was repeatedly accused of being an adherent of the Taliban or al-Qaeda, and punished with blows to the face and body each time he denied the charge.

“Hour upon hour, they repeated the same questions accompanied by punches and kicks,” he relates. “I don’t know how long I was interrogated that day. But I can still remember the words [the interrogator] kept repeating”: “You’re a terrorist! We know that. We’re going to keep you forever. You’re never going home!”

Those were exactly the same words recited over and over to Alexander Dolgun. And the methods employed in an attempt to break Kurnaz’s spirit were likewise Sovietesque: He and other detainees were fed a severely restricted diet — sometimes around 600 calories a day; they were exposed to severe cold while being bombarded with unbearably loud rock and rap “music”; they were systematically deprived of sleep and forced to endure lengthy night interrogations.

When those methods failed to elicit a confession, Kurnaz was subjected to electroshock torture and ultimately to controlled drowning — commonly called “waterboarding.” In his case, Kurnaz’s head was held underwater by one assailant as a second punched him in the stomach, forcing him to take reflex breaths. He was hung for hours suspended from the ceiling, his only relief coming when a physician was summoned to determine whether he was still alive.

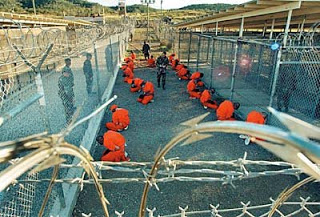

After surviving roughly two months at Bagram Air Base in Afghanistan, Kurnaz was flown to Guantanamo Bay. During the 27-hour flight, “soldiers kept hitting us to keep us awake.” This treatment continued during his confinement: “Everu few minutes, guards came and pounded on the fence with their nightsticks.

One insight Kurnaz gained into the minds of his tormentors was that their chief motivation was fear — not only of the “terrorist threat” in general, but of their prisoners. The typical guard was bold as Achilles and full of profane bluster when his victim was chained to the floor of a tiny cell or wrapped up like a package and surrounded by other military personnel in heavy armor. But even then, Kurnaz occasionally saw undisguised fear radiating from the eyes of his captors.

Whenever he was summoned for interrogation, Kurnaz was surrounded by an armored “escort team”; any violation of the arbitrary — and ever-changing — rules of prisoner conduct provoked an attack by the “Immediate Reaction Team” (IRT), a unit consisting of “five to eight soldiers with plastic shields, breastplates, hard-plastic knee-, elbow-, and shoulder-protectors, helmets with plastic visors, gloves with hard-plastic knuckles, heavy boots, and billy clubs.”

The IRT would be summoned to inflict punishment for any unauthorized display of individual assertion — such as an insult hurled at an abusive guard, or even an attempt to exercise. Typically they would infuse the cell with crippling tear gas — aerosolized oleoresin capisicum, derived from chili peppers — and then, once the prisoner had been left entirely incapacitated, the IRT would swarm him to deliver a beating.

Even then, recalls Kurnaz, he “often saw fear in their eyes as they stood in front of our cages and waited to be deployed, even though we didn’t have shoes on and were already cowering on the ground.”

What he detected was the irrepressible, instinctive fear of a bully who knows that someday, somehow, his victims will retaliate. In other words, he discerned, in microcosm, the elemental impulse that drives much of U.S. foreign policy.

At some point, physical mistreatment becomes otiose as the victim adapts. This means that torturers have to devise other ways of inflicting misery. Kurnaz recalls a session with his interrogator at Gitmo, an American military officer who spoke fluent German, in which the detainee was shown numerous newspaper stories — exercises in statist stenography presented as journalism — uncritically retailing the Regime’s accusation that Kurnaz was a “German Taliban” who had been captured in a bold Special Forces operation in Afghanistan.

“But you know I that I was captured in Pakistan,” he protested.

“Yes, we know it,” his interrogator smirkingly replied. “But the people on the outside don’t know it. It’s none of our business. Journalists write whatever they want.”

This is another tactic borrowed from the Soviet secret police: Planting false stories about their victims in controlled media as a way of undermining their resistance.

War criminal: Major General Geoffrey Miller may look a bit like Colonel Saul Tigh from Battlestar Galactica, but he has none of Tigh’s tragic nobility. Miller took command of the Guantanamo Bay detention facility in late 2002, and immediately escalated the use of torture — sleep deprivation, arbitrary beatings, subjection of prisoners to extremes of heat and cold. The prisoners eventually retaliated on one occasion by baptizing him with the contents of their chamber pots — the only recorded instance in which human waste was defiled by contact with something even more disgusting.

And still the torture continued. Because he adamantly refused to confess, Kurnaz was one of five Gitmo detainees selected for “Operation Sandman,” a lengthy exercise in enforced sleep deprivation in which teams of guards would move the prisoners from cell to cell for days on end, forbidding them to sleep for longer than a few minutes at a stretch.

On one occasion, Kurnaz was finally driven beyond forebearance. Offered the opportunity to shower — a concession made rarely and on a completely random basis — Kurnaz was given a split-second to wash before the water was turned off. Chained once again for return to his cell, he was jerked around sadistically by a smirking young punk of a guard. Despite the shackles on his hands and feet, Kurnaz managed to grab hold of his tormentor, who ineptly attempted a Judo throw — only to have it reversed by the chained prisoner. The guard fell to the floor and absorbed a knee to the ribs and a headbutt to the face before Kurnaz was swarmed and dragged away.

“You’re not a man!” Kurnaz shouted at the guard. “I beat you up when I was in handcuffs and shackles.”

The IRT was summoned to gas and pummel Kurnaz, as the guard — his nose still bloody — sneered: “This is how we do it here.”

“That still doesn’t make you a man,” Kurnaz gasped before unconsciousness claimed him.

He was dragged away to a solitary confinement complex called “India,” a pod of sealed individual cells made of corrugated tin and arranged to be in direct sunlight. Once Kurnaz was inside, the air conditioning — the sole source of ventilation — was turned off; it was allowed to operate only after Kurnaz was reduced to unconsciousness by hypoxia.

Kurnaz was confined to India, and forced to undergo controlled asphyxiation, for 33 days.

It’s important to understand that almost all of the misery Kurnaz endured at Guantanamo came after he had been cleared of any connection to terrorism. As early as February 2002, German intelligence officials had concluded that there was no “direct” evidence that he was involved in terrorism; a September 2002 memo written by a German intelligence officer confirmed that Kurnaz was among the “considerable number” of Gitmo detainees who were “not part of the terrorist milieu.”

Another document dated September 26 of that year reported that “the U.S. sees Murat Kurnaz’s innocence as established” and predicted that he would be freed within six to eight weeks.” By this time, however, three governments — those in Washington, Berlin, and Ankara — had decided that freeing Kurnaz without forcing him to admit to something was simply unacceptable.

As one of Kurnaz’s fellow detainees, a man named Nuri, observed: “Do you think they’ll simply let us go, after all they’ve done to us?”

So for nearly four more years, this innocent man was beaten, starved, tortured, subjected to endless persecution in the form of interrogations designed to elicit perjured self-incriminating testimony. On September 30, 2004 — two years after his innocence had been established — Kurnaz was brought before a Combatant Status Review Tribunal staffed with officers who had access to the exculpatory 2002 memoranda. That august panel designated Kurnaz an “enemy combatant” on the basis of “evidence” it didn’t deign to share with the detainee or his assigned military lawyer, who was utterly inert during the proceedings.

In January 2005, federal district Judge Joyce Hens Green ruled that the Combatant Status Review Tribunal had violated every known principle of due process in summarily designating detainees as “enemy combatants” on the basis of flimsy, classified, or suppositious “evidence.” Judge Green took particular notice of Kurnaz’s case as illustrative of the abuses committed by that system.

This was, in effect, the third time Kurnaz had been acquitted of terrorism charges. And he still had to spend nearly another year and a half in the Gitmo gulag before he was finally released. It’s entirely possible he would still be there — or dead — if not for the intervention of German Chancellor Angela Merkel and the work of Baher Azmy, an Egyptian-American attorney who volunteered his services on behalf of Murat.

In seeking to justify Kurnaz’s detention, the Bush Regime first claimed that one of his friends was a suicide bomber. “Leaving aside the astonishing legal proposition that one could spend the rest of one’s life in prisoner because of the unknown acts of a friend,” notes Azmy, this charge was “factually absurd” — since the purported suicided bomber was alive and well and was contacted without much trouble to file an affidavit “stating that, `um, I am alive.'”

The second charge was that Kurnaz was captured bearing arms against the Northern Alliance in Afghanistan. That charge was made by the same authorities who knew that he had been captured in Pakistan, because they bought him from Pakistani authorities. The final charge was that Kurnaz had effectively given material support to terrorism because of his association with an Islamic religious society whose membership contained a few people who may have made donations to other groups connected to terrorist groups. It was this distant and attenuated relationship that supposedly justified the decision to designate Kurnaz an “enemy combatant” — and that prompted the ruling from federal district Judge Green.

Still, even after it was abundantly and redundantly clear that Kurnaz wasn’t a terrorist of any kind, the Regime still tried to extract some victory over the innocent man it had imprisoned and tortured for so long. Negotiations with the German government dragged on for eight months, with Washington demanding that Kurnaz, once released, continue to be treated as a prisoner: His passport was to be confiscated, he was to be subject to preventive detention on the flimsiest pretexts, and be kept under constant surveillance. To its credit, the German government rebuffed those demands.

Finally, in August 2006, Kurnaz was told that he was to be released. But just before boarding the military transport plane to take him — bound, shackled, and in goggles once again — to Ramstein Air Base in Germany, Kurnaz was confronted by an American officer who shoved a document in his face:

“`Sign this piece of paper,’ he said, `saying that you were detained in Guantanamo Bay because you are linked to al Qaeda and the Taliban. Or you are never going home.”

To his eternal honor, Kurnaz refused.

I’m inclined to think this was his way of tacitly saying, “I f**k the State.”

Kurnaz’s memoir, most of which deals with his experiences in Cuba, brings to my mind another account of suffering in a Cuban gulag: Against All Hope by former Cuban dissident poet Armando Valladares. Mr. Valladares, who spent more than twenty years in Castro’s gulag, recalled that among the most energetic torturers employed by the Cuban regime was an American ex-military officer identified only as Captain Marks, who would beat inmates and threaten them with his trained German Shepherd.

Which is to say that Captain Marks performed for Fidel Castro the same kind of heroic service being carried out today by many of our valiant troops at Gitmo today. In fact, it would surprise me to learn that Marks had re-upped, given that his skills are in such demand by our own Torture State.

Those who control our corporatist system have a perverse genius for commercializing atrocities.

“It’s an interesting bit of consumerist trivia, an absurdly dark one really, when one considers that just about a mile from the strip mall housing [various American fast-food franchises at Guantanamo Bay] and other fronts of innocent Americana, there existed a camp housing a fully constructed project of dehumanization,” writes Baher Amzy in an epilogue to Kurnaz’s book.

And now that Gitmo’s horrors have been mitigated ever so slightly, the merchandising has begun. Witness — if you can bear to — the spectacle of “Taliban Towers,” a tourist getaway at Guantanamo Bay open to those who belong to the Regime’s armed forces or who are employed by various military contractors to provide the Empire’s critical infrastructure.

For a price of $42 a night — roughly what a civilian pays stateside for a night at a Motel 6 — servicemen, contractors, and their dependents can wind-surf, go deep-sea fishing, and enjoy the amenities offered by a full-service resort within easy walking distance of a literal American Gulag.

Dum spiro, pugno!

Content retrieved from: http://freedominourtime.blogspot.com/2008/05/american-gulag.html.