Tuesday, March 24, 2009

Liberty and Law, not “Law and Order” (Brief Programming Update, 3/26)

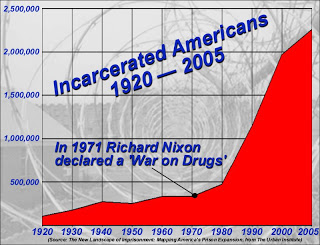

With our days as a manufacturing power a wistful memory and the marketing of fraudulent Wall Street “financial products” an infinitely self-replenishing source of national outrage, incarceration may soon become — by default — our leading national industry.

With our days as a manufacturing power a wistful memory and the marketing of fraudulent Wall Street “financial products” an infinitely self-replenishing source of national outrage, incarceration may soon become — by default — our leading national industry.

The United States is notorious for having the world’s largest prison population: As

the International Herald Tribune notes, the U.S., with five percent of the world’s population, but nearly one quarter of the world’s prisoners.Although our rate of violent crime is high among “developed” nations, the size of the American prison population isn’t a product of a uniquely depraved population. It is, in large measure, a product of an exceptionally punitive “justice” system, which reflects a strong streak of cultural vindictiveness — or what the Herald Tribune calls “populist demands for tough justice.”

Following his tour of American penitentiaries in 1831,

Tocqueville was prompted to write that “In no country is criminal justice administered with more mildness than in the United States,” a practice that contrasted favorably with the legal practices of the British, who were “disposed … to retain the bloody traces of the dark ages in their penal legislation.”The French sociologist was careful to contrast the light touch of American penology with the “barbarous” treatment meted out to slaves. His observations led him to believe that the disparities in treatment reflected the fact that convicted criminals were seen as errant social equals, and black slaves were not. Americans, Tocqueville concluded, looked upon slavery “not only as an institution which is profitable to them, but as an evil which does not affect them.”

Were he to make a similar survey of 21st century American prisons, Tocqueville most likely would find little of the “compassion” and “mildness” he discerned in America during its robust republican youth. As the International Herald Tribune observes, “Americans are locked up for crimes — from writing bad checks to using drugs — that would rarely produce prison sentences in other countries. And in particular they are kept incarcerated far longer than prisoners in other nations.”

Perhaps the single largest contributing factor, of course, is the prohibitionist impulse, or what the Herald-Tribune describes as a “special fervor in combating illegal drugs.”

To an extent unrivaled in the Western World, and perhaps comparable only to the People’s Republic of China, America’s prison system is populated by non-violent offenders. This is due primarily to that inexhaustible well of policy foolishness known as the “war on drugs,” of course.

Another significant element in this equation is the use of jails and penitentiaries as “debtor’s prisons” for “deadbeat dads” — divorced fathers driven into intractable financial misery by the federal child support racket.

Dr. Stephen Baskerville of Patrick Henry College, author of the indispensable study Taken Into Custody, offers a tidy description of the child-napping and extortion racket in operation:

“A parent [generally a father] whose children are taken away by a family court is only at the beginning of his troubles. The next step comes as he is summoned to court and ordered to pay as much as two-thirds or even more of his income as `child support’ to whomever has been given custody. His wages will immediately be garnished and his name will be entered on a federal register of `delinquents.’ This is even before he has had a chance to become one, though it is also likely that the order will be backdated, so he will already be delinquent as he steps out of the courtroom. If the ordered amount is high enough, and the backdating far enough, he will be an instant felon and subject to immediate arrest.”

Jails and prisons across our land bulge at the seams with men who have been sucked into this vortex. Countless others are on probation, parole, or shackled at the ankle with electronic monitoring devices.

Baskerville’s book describes the intricate system of federal subsidies and incentives that created this debtor’s gulag. The federally funded army of prosecutors, bureaucrats, counselors, and assorted buttinskis devoted to the war on fatherhood is thirteen times larger than the force mustered to fight the “war on drugs.”

In addition to those two federally instigated “wars,” the county jail populations are plumped out by local campaigns against other forms of non-violent “crime” — generally repeat or compound violations of traffic regulations or “quality of life” ordinances.

For an exceptionally silly example of this kind of thing we can look to Orlando, Florida, where 22-year-old activist Eric Montanez was arrested — following an undercover police operation — for violating a municipal ordinance by feeding more than 25 homeless people in a public park. (That Montanez is distantly affiliated with ACORN and like-minded outfits doesn’t make the ordinance and less asinine.)

Douglas A. Blackmon‘s recent book Slavery by Another Name seems to confirm that such cynical suspicions are amply justified.

Blackmon’s research, which appears valid and compelling, leads him to conclude that municipal ordinances in post-Emancipation South were designed and enforced with the purpose of producing large pools of inmate labor to be leased to large corporate interests. Other versions of this analysis had been advanced earlier in criminologist Thorsten Sellin’s study Slavery and the Penal System, and David Oshinsky’s book Worse Than Slavery.

Blackmon’s book begins with the account of 22-year-old Green Cottenham, a young man arrested for “vagrancy” by the sheriff of Shelby County, Alabama. “Vagrancy” the stickiest of catch-all charges used to round up anyone unable “to prove at a given moment that he or she [was] employed.”

At the time and place of Cottenham’s arrest, the charge was most frequently used to justify the arrest of young black men, many of whom were unemployed itenerant workers looking for employment. Cottenham was quickly convicted following a burlesque of a trial and sentenced to thirty days of hard labor.

In a fashion immediately familiar to most people incarcerated today, Cottenham was unable to pay an array of “fees” that accompanied his spurious incarceration. So the thirty-day sentence was quickly expanded to a full year. Immediately thereafter, Cottenham was “leased” — or, as his parents, both of whom former slaves, would put it, sold — to the Tennessee Coal, Iron, and Railroad Company, a subsidiary of U.S. Steel.

“Imprisoned in what was then the most advanced city of the South, guarded by whipping bosses employed by the most iconic example of the modern corporation emerging in the gilded North, [Cottenham and his co-workers] were slaves in all but name,” observes Blackmon.

Thousands perished from disease, overwork, and accidents, their mortal remains interred in shallow graves not far from where they expired. This was a continuation of slavery by other means, of course. But the system described by Blackmon — opportunistic law enforcement feeding non-violent offenders into a penal system hard-welded to government-favored corporations — exists today.

As a recent report notes, “Private corporations are making a killing employing prisoners across the US. They are hiring the incarcerated to manufacture everything from designer jeans to computer circuit boards.” Mother Jones magazine compiled an impressive list of products — from dressed beef to packaged software and videogames — turned out by inmates paid less than a pittance.

A large portion of the inmate labor is provided through Unicor, a public-private partnership created during the (last) Great Depression to create “factories with fences.” It’s difficult to see how this operation differs in principle from China’s notorious and brutal Laogai (reform through labor) prison manufacturing system, which may actually be smaller than its U.S. analogue.

There are indications that the prison-industrial complex is suffering some financial setbacks as a result of the ongoing economic collapse. Across the country, budget cuts made necessary by depleted sales and property tax revenues are forcing courts and sheriff’s departments to relent in their pursuit of non-violent offenders, and to explore alternatives to incarceration.

This is a positive and encouraging development, an illustration of the corrective effect of an economic contraction. Ideally, states and municipalities would be compelled to abandon incarceration as a punishment for anything other than actual crimes against persons and property, and then to use that option sparingly in dealing with only the most serious offenses.

In colonial and early post-independence America, jails were uncommon and penitentiaries all but unknown. In many communities those convicted of property crimes were compelled to make restitution to their victims, a practice growing out of the recognition that such offenders owe a debt to particular victims, not to a collectivist abstraction called “society.”

If the economic correction we’re experiencing were to result in a much-overdue social correction, the existing “justice” system would be demolished and reconstructed on the basis of liberty protected by law, rather than “law and order.” The purpose of the law, wrote John Locke in his Second Treatise of Government, “is not to abolish or restrain but to preserve and enlarge freedom.”

The preservation of individual liberty and property requires a government apparatus so minimal as to be practically invisible, and a law enforcement touch so slight as to be nearly imperceptible.

This is why our rulers have spared no effort to propagate and maintain a cult of “law and order,” in which the supposed needs of “society” are paramount and justice for individual victims of actual crimes, where it occurs, is a fortuitous but inconsequential happenstance.

And this is why the next priority of the Obama administration’s “stimulus” fraud — after putting the most corrupt elements of Wall Street in charge of the public purse, and ensuring that the Democratic Party’s esurient constituencies are well-fed — will probably be a “surge” of funding for the “law and order” apparatus, which will probably open up a lucrative new affiliate devoted entirely to the apprehension and punishment of incorrigible political troublemakers.

Housekeeping/Personal Affairs UPDATE, March 26

I appreciate your patience during a lengthy hiatus between postings. My family and I are traveling right now in a combined mini-vacation and job search. I’ve got portions of two essays written and a third in a preliminary outline stage, so you can expect the op-tempo to pick up dramatically as soon as I can spend more time with my fingers on the keyboard, rather than wrapped around a steering wheel. Thanks!

On sale now.

Dum spiro, pugno!

Content retrieved from: http://freedominourtime.blogspot.com/2009/03/liberty-and-law-not-law-and-order.html.