Among the common beliefs of libertarians, opposition to slavery is one of the least controversial. Yet, the moral argument against slavery is one of libertarian philosophy’s most enlightening topics. Considering the “why” of libertarian opposition to slavery is profoundly instructive. Libertarianism approaches the question of individual rights in a unique way.

In my opinion, the cornerstone of libertarian philosophy lies with its answer to the is-ought dichotomy presented in David Hume’s skepticism. From the far right, idealism is an absolute that tramples upon those who are different. From the far left, anti-idealism destroys morality, community and tradition – leaving behind an unprincipled bureaucracy that tramples in the name of expediency and arbitrary intellectual fashions. The best course lies with a balance, where absolute idealism and subjectivity exist only in context with one another. This context can only be found within the individual mind. Morality, therefore, is a product of individuals reconciling the rational and emotional within themselves, and then confronting the consequent social reality. Libertarianism proposes a social environment where personal morality is respected and reconciling the individual right to moral self-determination between people with different beliefs and ideas is the core principle of politics.

The reconciliation of is and ought was a project of the Scottish Enlightenment, in the school of Common Sense (Thomas Reid). This school was heavily influential among the French liberals who later influenced both Bastiat and eventually the Austrian school of economics. The Common Sense school also served as the intellectual and religious foundation of New England’s revolutionary liberty movement.

The American revolution must be seen as an alliance between Virginia old England aristocrats, seeking to maintain ancient yeoman rights, and New English Christian anarchists who possessed a religious ideal of human liberty. The former felt that society’s rights were protected in its Anglo-Saxon traditions and were to be defended existing, enlightened aristocratic social structures. They conceived of the US Constitution’s form without perceiving a need for enumerated rights. The State was the political society – the tobacco lords and their custom of mutual political equality. Jefferson broadened the notion by conceiving of a yeoman farmer class related to a romanticized vision of England’s past and Virginia’s present.

New England, on the other hand, saw individual rights as derivative of holy truths discerned by the heights of enlightenment and Christian thought. They demanded the Bill of Rights.

The school of Common Sense led to a short-lived tradition within British liberal Christianity which held that science and religion must, according to the nature of each, exist in perfect harmony. If science and religion stood in contradiction, it meant that the interpretation of evidence or scripture must somehow be flawed. Out of this thinking, the Common Sense school developed a sophisticated moral science with an extensive vocabulary describing a person’s moral duties in the context of unalienable rights given by God. As science and religion ultimately diverged in the late 19th century, this philosophy fell out of favor.

Common Sense philosophy and the moral ‘science’ of the so-called Christian Enlightenment should be more widely appreciated within libertarian community. The content of this ‘science’ applies to modern questions, so long as one possesses a key to interpret the religious concepts in secular terms. This isn’t very difficult to accomplish, since the Christian Enlightenment was already quite ameliorable to science.

The question of is-ought is simply a question of mind and soul. Reason and emotion. The answers of the Common Sense school are self-evidently superior, and the reason for its decline in popularity is clear. The question of soul and mind is one philosophy grappled with, using great energy, for two hundred years before the question was finally swept aside by the great and terrible intellectual winds that accompanied imperialism. Imperialism, the systemization of pure war, the categorization of all into a utilitarian, all-consuming whole; a system of mortal contest between powers, a race to the bottom, a fiendish quest to consume, destroy, repeat. This gave us the atomic bomb and the Holocaust, among other outcomes.

In contrast to 20th century’s outcomes, the spirit of 1776 was fueled by a philosophy of freedom. The people learned from New England preachers teaching of the unity of mind and soul within the individual, who stands as a moral self-sovereign. The importance of liberty was self-evident to them, as real as the green grass and God above.

The philosophical spirit of 1776 is the same spirit that abolished slavery. This does not refer to the American Civil War. While it’s true that the Civil War was fought in the context of slavery, it was a war over tariffs and power. Its concern with slavery was related to the treadmill of empire building, as a more efficient, modern version of empire overthrew an earlier less efficient system of slavery and exploitation.

In this political environment, it was the moral philosophy of the anti-slavery movement which made ending slavery an absolute condition of the Empire’s progress. We can disdain empire, but we ought to respect the manner in which it was compelled to extend rights to freed slaves. The Emancipation Proclamation freed few slaves, as those areas under federal control were not subject to emancipation. It was the 13th Amendment which freed the slaves, and it was the moral stubbornness of the anti-slavery movement that mandated the necessity of the 13th Amendment.

Whether in the American anti-slavery movement, or in the efforts of William Wilberforce in the UK, it was the moral and philosophical foundation of the British Christian Enlightenment which made slavery morally and politically anathema. Never before in history had an absolute moral argument against slavery been made. Even the New Testament apostles didn’t condemn the practice utterly. The basic foundations of anti-slavery, democracy and human rights are found in the Christian Enlightenment of British Liberalism.

Although the world today couldn’t care less about liberty, the so-called ‘liberal world order’, pretentious as it is, derives from the Christian Enlightenment. The moral science derived from Common Sense more or less conquered the world. While Locke might speak of civil and property rights, John Stuart Mill of personal liberty, it is Common Sense that speaks of the moral worth and essential spiritual equality of man.

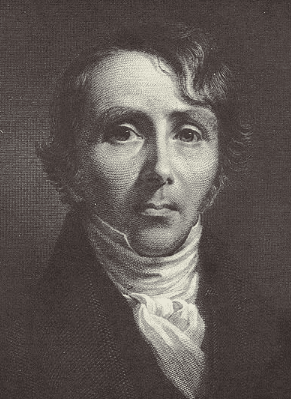

William Ellery Channing was a New England preacher from the early 19th century. He was a Unitarian, and was trained in the moral science of the Common Sense school of philosophy – the staple teaching at Harvard University before the arrival of continental (Prussian) influence. He was the key figure of his movement in the age just prior to Unitarianism’s digression into bizarre Transcendentalism. He took the moral science of the Common Sense school and the liberal interpretation of Christianity to their absolute heights. Naturally, he had things to say about slavery.

Channing’s thoughts about slavery, penned somewhat early than any major political tensions emerged surrounding the issue (outside of Massachusetts high society), were recorded in a sermon treatise released in 1833 simply titled, Slavery.

Channing’s argument against the practice of slavery invokes some of the core principles of his moral philosophy. I will review what he wrote and relate it to modern day society. Although the subject is slavery, which is non-controversially bad, the arguments against it serve to defend against modern day political ideas which are sometimes quite popular. By understanding the moral argument against slavery which was used by Common Sense school philosophers, one can have a deeper comprehension of the philosophy of individual rights.

Lofty and Pure Sentiment

As Channing begins his treatise on slavery, he frames the core belief behind his argument: the central importance of human morality, it being derivative of a power greater than any which can be constructed by man.

“There is but one unfailing good; and that is, fidelity to the Everlasting Law written on the heart, and rewritten and republished in God’s Word.

“Whoever places this faith in the everlasting law of rectitude must of course regard the question of slavery first and chiefly as a moral question.

“There are times when the assertion of great principles is the best service a man can render society.

“A community can suffer no greater calamity than the loss of its principles. Lofty and pure sentiment is the life and hope of a people.

“Such ought to remember that to espouse a good cause is not enough. We must maintain it in a spirit answering to its dignity.”

Although the introductory portion of Channing’s argument invokes religion, the philosophical point he hopes to convey is central to his entire critique of slavery. His religious belief equates that which is written on the heart to that which is recorded in religious scripture. In Unitarian moral philosophy, the conscience is the center of all moral decision making. The conscience represents the union of rational thought with sentiment. It combines the oughts of life – our desire for happiness – with the logically deduced principles and rights which support happiness. Devotion to morality, or “the Everlasting Law,” is nothing more or less than a principled commitment to the rational pursuit of that which motivates us as individuals, including that which we have in common between us as human beings.

Channing claims that a community can suffer no greater, “…calamity…,” than the loss of its principles. Later in his sermon, he exalts the moral worth of a society above its material and economic worth. He argues that wealth serves a higher cause, and that it has no inherent value beyond the cause which it serves. While for some the cause of life might pertain to a higher supernatural plane, in Channing’s moral science the principles and aspirational sentiments associated with what we call heaven can be expressed and achieved also on Earth (not meaning to build heaven on Earth, but to strive to be nearer to worthiness of heaven while on Earth). This comports to an easy secular interpretation.

Life’s value is ineffable. We can’t scientific prove why it matters or not. However, most of us place value on living life. We aspire and experience longing. Though the object of our longing differs in form from person to person, the essence of longing is the same. We live life in search of something which is valuable to of us. That thing, that value, and the longing for it in the form of sentiment, represent the lofty and pure heights to which we aspire. Channing’s moral argument is that if a society cannot resolve to devote itself with clear mind and conscience to whatever it is we long for, then our life is a waste.

Only societies which prioritize moral principles as bedrock values will be worthy of obtaining the object of their longing. By stating this, Channing sets out stakes. If slavery cannot be considered moral, it cannot be permitted by a society which hopes to thrive.

Why Humans Can’t Be Property

Channing’s first substantive topic is about property. Here he argues that a human cannot be property. He presents the notion as a fallacy, reviewing many reasons why the concept of ownership of humans is morally and logically incorrect.

His first argument proposes that slavery depends upon a contradictory principle, relying on a notion of inequality which is not present in the Lockean philosophy of property rights.

“It is plain, that, if one man may be held as property, then every other man may be so held.

“If there be nothing in human nature, in our common nature, which excludes and forbids the conversion of him who possesses it into an article of property; if the right of the free to liberty is founded, not on their essential attributes as rational and moral beings, but on certain adventitious, accidental circumstances, into which they have been thrown; then every human being, by a change of circumstances, may justly be held and treated by another as property.

“The consciousness of indestructible rights is a part of our moral being. The consciousness of our humanity involves the persuasion, that we cannot be owned as a tree or a brute. As men we cannot justly be made slaves. Then no man can be rightfully enslaved.”

This argument applies especially to Americans, who had in living memory defended their natural rights against a tyrant (the treatise was written in 1833). The American assertion to liberty invalidates the logic of slavery. If some men can be enslaved, then any man could be; in an environment that permits slavery, American claims to liberty and rights are invalid.

The natural rights associated with American liberty come from the philosophies of British Liberalism, which has all but died out among governments and academics and is dying out among Western professional organizations. However, the formal world order is ironically grounded in these same principles as the foundation of the premise of universal human rights.

The flaw of modern political trends lies with their overreliance on experts wielding power, which contradicts the premise of universal human rights. Any technocratic order which seeks to deny rights to people via removing their privacy, taxing them without recourse, denying them the right to self-defense and so forth, must nevertheless be led by a class of experts. Human rights, in this environment, must be gifted by the experts. The clear implication is that human rights can be modified if the experts deem it necessary.

The depravities of communist regimes give plentiful examples of the principle of conditional rights. If American society will go towards a direction where more and more elements of society are managed by technical experts, then it must do so while preserving individual self-determination. If experts aren’t managing at the pleasure of the managed, then human rights can’t exist. Human rights assume a fundamental moral equality between humans, and the concept of expert rule flies in the face of that assumption.

Channing’s next argument references rights. It is a bit archaic. In Southern slavery, slaves were considered nevertheless to be men who held rights. For instance, it was illegal to murder slaves. Channing takes for granted that his audience has already conceded some rights to slaves.

“A man cannot be seized and held as property, because he has Rights.

“Now, I say a being having rights cannot justly be made property; for this claim over him virtually annuls all his rights. It strips him of all power to assert them. It makes it a crime to assert them. The very essence of slavery is, to put a man defenceless into the hands of another. The right claimed by the master, to task, to force, to imprison, to whip, and to punish the slave, at discretion, and especially to prevent the least resistance to his will, is a virtual denial and subversion of all the rights of the victim of his power.”

This argument is more profound than it first appears. Generalized, the argument says that if some rights are possessed by a man, then he must possess all the rights which are natural to all men. Later, Channing discusses rights in greater detail, devoting an entire chapter to them. He includes a deeper discussion of where rights come from. Suffice it to say that rights are purposeful. Rights are not entitlements, being only a stronger version of privileges. In Channing’s moral worldview, rights are instruments or tools which pertain to the purpose of man’s being. Rights exist to provide man a means to carry out that purpose. If one ounce of that purpose is acknowledged, if any means to accomplish that purpose are permitted, then one must permit them all, or else invalidate the both the man’s purpose and existence.

If a man doesn’t exist to fulfill his own happiness within his means, then his life is null. To enslave a man is to murder a man, from the perspective of the moral guilt of the perpetrator. It is to deem the fulfillment of happiness of one person to be irrelevant, while simultaneously pursuing one’s own fulfillment of happiness. It is a moral contradiction that can only persist in an environment of unmoderated lusts and unlimited violence. While slavery in its heyday purported to be within a moral framework, the abundant rape and violence committed by slavers against slaves, without punishment, is proof of the harms stemming from slavery’s contradiction of moral principles.

The principle of moral consistency supports the notion of the equality of man. There is no scientific proof that life matters. Consequently, the value of life exists only as a subjective assertion on the part of any individual human. Logically, morally and legally, the assertion of life’s value from one man to the next is inherently equal. Human inequality cannot be supported morally, and systems that assert moral inequality can only be sustained through perpetual violence.

Channing explains why even outward differences between men, in ability and birth, do not abolish the fundamental moral equality of men.

“Another argument against property is to be found in the Essential Equality of men.

“All men have the same rational nature, and the same power of conscience, and all are equally made for indefinite improvement of these divine faculties, and for the happiness to be found in their virtuous use. Who, that comprehends these gifts, does not see that the diversities of the race vanish before them? Let it be added, that the natural advantages, which distinguish one man from another, are so bestowed as to counterbalance one another, and bestowed without regard to rank or condition in life. Whoever surpasses in one endowment is inferior in others. Even genius, the greatest gift, is found in union with strange infirmities, and often places its possessors below ordinary men in the conduct of life. Great learning is often put to shame by the mother-wit and keen good sense of uneducated men. Nature, indeed, pays no heed to birth or condition in bestowing her favors. The noblest spirits sometimes grow up in the obscurest spheres. Thus equal are men; and among these equals, who can substantiate his claim to make others his property, his tools, the mere instruments of his private interest and gratification? Let this claim begin, and where will it stop? If one may assert it, why not all?

“Who of us has no superior in one or the other of these endowments: Is it sure that the slave or the slave’s child may not surpass his master in intellectual energy or in moral worth? Has nature conferred distinctions which tell us plainly, who shall be owner? and who be owned? Who of us can unblushingly lift his head and say that God has written ‘Master’ there? or who can show the word ‘Slave’ engraven on his brother’s brow?”

The equality of man, taken together with Channing’s point about rights, proves that government must serve at the mercy of the people. Government cannot legitimately defend a vision of society that it synthetically imposes upon that same society. The progressive notion of shaping society in a better direction (coercively) is immoral. It establishes an inequality, where one class of intellectual superiors arbitrarily designates those with whom they disagree as lesser, who only exist to serve the aspirations of their betters. Even when the aspirations of the betters purportedly include the betterment of the lessers, the principle still holds.

One may not keep a man in slavery simply because one asserts it is for the slave’s own good. Likewise, a coercive progressive state has no right to impose whichever intellectual fashion of the age upon the masses. This notion is morally indefensible, and again the progressive state truly realized will always collapse into violence and tyranny.

The foibles of the ‘uneducated’ must be tolerated by a moral society. They have a moral right to their ignorance. The harm that ignorance causes to society must be addressed in non-coercive ways. The experts also, from the perspective of the future, are themselves perfectly ignorant. There is no moral proof that the latter may rule over the former. We are all striving to do our best, and all of us are failing, though some of us may be ahead of others. Mutual betterment can only occur cooperatively.

Persuasion, rights-respecting boundaries and assertion of rights all serve as tools with which the more enlightened can interact with the less endowed. Both parties have rights, and within the scope of those rights, both are free to act how they choose.

Channing’s next argument relates to the theory of property itself.

“That a human being cannot be justly held and used as property is apparent from the very nature of property. Property is an exclusive, single right. It shuts out all claim but that of the possessor, What one man owns cannot belong to another. What, then, is the consequence of holding a human being as property? Plainly this. He can have no right to himself. His limbs are, in truth, not morally his own. He has not a right to his own strength. It belongs to another. His will, intellect, and muscles, all the powers of body and mind which are exercised in labor, he is bound to regard as another’s. Now, if there be property in any thing, it is that of a man in his own person, mind, and strength. All other rights are weak, unmeaning, compared with this, and in denying this all right is denied.”

This argument speaks for itself in a straightforward manner. A man and his body already belong to himself, his very birth the act of homesteading. No system which respects property rights can infringe upon this self-ownership and be taken seriously.

Even so, Channing exposits the principle beautiful. In his explanation, there are foreshadowed hints of Ayn Rand’s better angels, among parallels to the ideas of libertarian property theorists. Channing’s argument, though, adds a moral dimension. Property exists to serve man’s moral purpose, which is higher than his economic purpose. His moral purpose is the ultimate aim of his life as he sees it, the purpose for which he lives. By placing economic rights into the greater moral context, Channing shows that the greater right – moral self-determination – trumps any property right. Property in context only serves moral purpose.

Contextualizing property rights within moral self-determination represents an interesting argument that is not usually discussed in libertarian philosophy. Most property theory derives from the pure logic which results from examining a conflict situation. Property is simply the outcome of applying logic consistently to the nature economic behavior and conflict resolution. We must take an extra step, however, to ask why we care about pure logic. It’s true, the answers come easy: we want a peaceful, orderly society, among other arguments. Still, Channing’s answer is also very compelling.

Channing presents economic activity – what Austrian Economics calls human action – as an outcome of moral purpose. Channing presumes a longing – an ineffable ought – behind human action. The Austrians are somewhat ambivalent here. They admit that there must be some force behind human action, plainly acknowledge it, but they are neutral about what it must be. Channing’s worldview is at least substantively neutral. We are permitted to long for what we choose to long for. Yet, Channing introduces his own sentiments, assuming that there is some common feeling which can be observed as common between people. It is a sense of universal love and aspiration towards personal betterment. Regardless, even he would admit that he himself only wishes for this to be the outcome of society. It was his aspiration to establish a common sense of universal love in the human heart. His pursuit of this aim was through persuasion, not force.

Irrespective of the object of human longing, the presence of a greater, moral impetus behind human action slightly modifies libertarian thought. We can’t just take human purpose for granted and evaluate human action neutrally. Instead, we can observe the consequences of human action, and evaluate whether these consequences are consistent with whatever moral purposes were behind the action. It is a more holistic approach.

In politics and law, we establish systems to achieve ends. Political thought is rife with discussions of means and ends. However, rarely do we hear about motives. Channing’s worldview focuses first and last on motive, not neglecting means or ends.

Isn’t the slave motivated by the same feelings as the slave master? Do not both aspire to personal happiness as they see fit?

In libertarianism, our belief in freedom of the markets, in combination with the materialistic emphasis of our focus on rational thought, cause most of us to place great weight on the value of material wealth. We shouldn’t make the mistake, however, of thinking that it is material well-being which primarily motivates us as libertarians.

The values which motivate us as libertarians – or ought to: the commitment to moral self-determination – are why we support free markets and rational thought. The importance of wealth is derivative of economic freedom and reason.

If wealth must conflict with permitting moral self-determination, we must remain true to our principles. Moral freedom trumps. This is true for an obviously controversial practice such as slavery, but also true for subtler practices. Perhaps there are times when the landlords’ rights might not always trump the squatters’, or at least times when the landlord might discover a heart full of charity.

Libertarianism is odd among economic philosophies in that it values the principle of wealth more than wealth itself. Certainly, this attitude does always not contribute well to the movement’s influence in society.

Slavery in antebellum America existed in a context where the slave trade was considered immoral and abhorrent. There were self-serving reasons why the Southern slavers banned new slave imports (it increased the value of domestic slaves). Even so, the official moral position of the slaver society was that the creation of new slaves was illegal and immoral. Many defenders of slavery insisted that theirs was an inherited, unwanted stewardship over a lesser, unruly people. Even those who saw Africans as essentially equal to Europeans still concluded that the conditions of being raised in slavery would prevent a population from safely integrating into the American system of personal liberty. The slavers argued that they were ultimately guilty of no crime, and the only guilt lay with the original perpetrators who first engaged in the slave trade. Channing addresses this argument.

“We have a plain recognition of the principle now laid down, in the universal indignation excited towards a man who makes another his slave. Our laws know no higher crime than that of reducing a man to slavery. To steal or to buy an African on his own shores is piracy. In this act the greatest wrong is inflicted, the most sacred right violated. But if a human being cannot without infinite injustice be seized as property, then he cannot without equal wrong be held and used as such. The wrong in the first seizure lies in the destination of a human being to future bondage, to the criminal use of him as a chattel or brute. Can that very use, which makes the original seizure an enormous wrong, become gradually innocent?”

The principle of moral philosophy espoused above deals with chains of guilt. It is an anti-conservative argument. If a situation derives from a crime, some restitution of the original crime, in proportion to that crime, must be undertaken.

In my opinion, calls for federal cash to be doled out as slavery reparations is absurd. However, a more aggressive level of social assistance to impoverished black communities is morally appropriate. From a moral point of view, American society was guilty of coercively immigrating black slaves, then perpetually reaffirming the minority status of their descendants on the basis of skin tone. That deserves a moral redress. It should occur or should have occurred in the form of more engagement. The current strategy for reconciling cultural differences within America takes the form of welfare checks and long-term prison internment, along with various forms of discrimination, nasty and subtle, combined with probably ineffectual academic support.

Much can and should be said about academic affirmative action. The political state of academia is miserable. Affirmative action in education is meant to improve the socio-economic conditions of an underserved community. Instead, young minority students have their resentments intellectually entrenched, while they receive expensive training that is unlikely to improve their future economic condition.

The majority community in America fails both to show mercy and penance adequately, while simultaneously lacking the ability to be tough. Persistent racism clashes with overly agreeable idealistic denial of endogenous problems facing minority communities. Even so, Channing’s appraisal of slavery’s moral status provides us with a moral solution this conundrum.

Morally, most of the problems within black communities have to be solved by black communities. However, it is appropriate to argue that it is impossible to morally disentangle black endogenous guilt from the moral history of the majority community which effectively created the condition of black society within America. It might be easy to say that enough time has passed, that it is now appropriate to leave the black community to solve its own challenges. Yet, the creation of black American society itself is the product of never addressed moral guilt. If immorality was ignored in the past, it cannot also be ignored in the future. Irrespective of the policy questions, the majority culture in America has a special moral obligation to not turn a blind eye to minority struggles.

Generalized, libertarians should not invoke individual rights as a moral absolution of the responsibility to be concerned with the condition of other people. We may not legally owe money or property to redress past social injustices, however, we do owe our concern and effort to help other humans. The spirit of charity should be morally inherent in libertarian philosophy. The reason is simply that justice is imperfect. While we would never go as far as John Rawls does, demanding legal institution of perfect justice, we can acknowledge that history and life are full of messy moral guilt. Therefore, in general, it is good to be charitable to one another. Rawls is partly correct.

The reason why Rawls is wrong lies embedded in Channing’s logic. Past guilt must be redressed in proportion. If modern day practices are just, and we argue that the injustice of past circumstances is the cause for reparations, then we can just as easily argue the reverse. Some portion of past actions may indeed have been perfectly just, and so the existence of some past injustices should not be license for present injustice. Rawls’ logic supports the morality of a general spirit of voluntary charity, as an important personal principle. It doesn’t support coercive reparations.

To reiterate, coercive charity is against libertarian principles, but a spirit of charity as a personal moral impetus ought to be a fundamental aspect of libertarian morality. Again, the reason is that the past is far too messy for anyone to make any absolute claims about justice. There will have been injustices, and will continue to be injustices, and that proposes a moral obligation on all members of society to do what they can to redress what they can.

Rights

“Another argument against the right of property in man may be drawn from a very obvious principle of moral science. It is a plain truth, universally received, that every right supposes or involves a corresponding Obligation. If, then, a man has a right to another’s person or powers, the latter is under obligation to give himself up as a chattel to the former. This is his Duty.

“He is bound to be a slave; … because another has a right of Ownership, has a Moral claim to him, so that he would be guilty of dishonesty, of robbery, in withdrawing himself from this other’s service. … Ought he not, if he can, to place himself and his family under the guardianship of equal laws? Should we blame him for leaving his yoke? Do we not feel, that, in the same condition, a sense of duty would quicken our flying steps? Where, then, is the obligation which would necessarily be imposed, if the right existed which the master claims? The absence of obligation proves the want of the right. The claim is groundless. It is a cruel wrong.”

If a man must be whipped and chained so that he remains a slave, doing what his master commands, then one cannot say that these commands represent the slave’s duty. The way Common Sense philosophy conceives of duty, it is intrinsic and related to rights as a natural foil. If people possess rights themselves, then intrinsically they have an attendant duty to respect the rights of others.

In libertarian philosophy we focus on that which is coercive. If so-called duty has to be enforced through coercion, then rights can’t exist. In short, no government can claim a moral right to tell anyone what their purpose is, or what they must do to be happy. Progressives claim a moral high ground, believing expert-run government to have a moral impetus to improve society. The unspoken implication is that humans must, by way of moral duty, support and sustain the government’s efforts to create the common good. However, if government doesn’t respect the moral self-determination of its citizens, then citizens have no conceivable obligation to sustain the moral authority of the government. It’s a matter of simply consistency and equality.

Channing, in a later chapter on rights, dismantles the government’s pretense at moral authority. Specifically, he discusses whether claims at improving the common good can supplant rights.

“Rights are made to depend on circumstances, so that pretences may easily be made or created for violating them successively, till none shall remain. Human rights have been represented as so modified and circumscribed by men’s entrance into the social state, that only the shadows of them are left. They have been spoken of as absorbed in the public good; so that a man may be innocently enslaved, if the public good shall so require.

“Still the question will be asked, ‘Is not the General Good the supreme law of the state? Are not all restraints on the individual just, which this demands? When the rights of the individual clash with this, must they not yield? Do they not, indeed, cease to be rights? Must not every thing give place to the General Good?’ I have started this question in various forms, because I deem it worthy of particular examination. Public and private morality, the freedom and safety of our national institutions, are greatly concerned in settling the claims of the ‘General Good.’ In monarchies, the Divine Right of kings swallowed up all others. In republics the General Good threatens the same evil.”

What, then, are the consequences of making the building of the “General Good” the supreme law of the land?

“It is a shelter for the abuses and usurpations of government, for the profligacies of statesmen, for the vices of parties, for the wrongs of slavery. In considering this subject, I take the hazard of repeating principles already laid down; but this will be justified by the importance of reaching and determining the truth. Is the General Good, then, the supreme law to which every thing must bow?”

Yet, if the common good is not to be the supreme aim of the state, what ought to be?

“The supreme law of a state is not its safety, its power, its prosperity, its affluence, the flourishing state of agriculture, commerce, and the arts. These objects, constituting what is commonly called the Public Good, are, indeed, proposed, and ought to be proposed, in the constitution and administration of states. But there is a higher law, even Virtue, Rectitude, the Voice of Conscience, the Will of God. Justice is a greater good than property, not greater in degree, but in kind. Universal benevolence is infinitely superior to prosperity. Religion, the love of God, is worth incomparably more than all his outward gifts. A community, to secure or aggrandize itself, must never forsake the Right, the Holy, the Just.

“Moral Good, Rectitude in all its branches, is the Supreme Good; by which I do not intend that it is the surest means to the security and prosperity of the state. Such, indeed, it is, but this is too low a view. It must not be looked upon as a Means, an Instrument. It is the Supreme End, and states are bound to subject to it all their legislation, be the apparent loss of prosperity ever so great.”

Channing boldly asserts what might be called the deontological argument over the consequentalist view of libertarianism. Yet, I believe he transcends the debate. By framing morality as an end, not a means, naturally Channing’s view opposed consequentialism. Yet, in Channing’s perspective moral rectitude is almost an economic product. It is not material, and yet, it is the outcome of a life dedicated to laboring for self-improvement. A society must labor, through education, endurance, mutual support and amidst material activity, to uphold moral principles. In this light, his argument is partly consequentialist. Since morals are the desired product and outcome of society, then moral consistency is the means to produce them. Moral rectitude is a consequence of moral self-improvement.

This argument may appear pedantic, even tautological to committed philosophical skeptics. Even so, the aim of Common Sense philosophy is to harmonize is and ought and consider them together. Morality is not merely perfecting our obedience to an arbitrary set of rules, to Common Sense thinkers, morality is harmonizing natural laws with inborne desires, and self-derived aspirations. Morality is inclusive of material ends, contextualizing them with human motives that inspire, incentivize and produce material ends.

If we exalt morality as the great End of human action, we are merely exalting our motivation for pursuing material ends along with the ends themselves.

My questions for all communists who wish to build heaven on Earth is: and then what, for what purpose, and, how do you know? The same can be said concerning the frailty of the consequentialist position.

Channing continues his discussion of society’s purpose and why the state’s infringement of rights cannot be justified by appeals to the common good. He addresses the idea of the state using its power to support national economic well-being.

“National wealth is not the End. It derives all its worth from national virtue. If accumulated by rapacity, conquest, or any degrading means, or if concentrated in the hands of the few, whom it strengthens to crush the many, it is a curse. National wealth is a blessing, only when it springs from and represents the intelligence and virtue of the community, when it is a fruit and expression of good habits, of respect for the rights of all, of impartial and beneficent legislation, when it gives impulse to the higher faculties, and occasion and incitement to justice and beneficence. No greater calamity can befall a people than to prosper by crime. No success can be a compensation for the wound inflicted on a nation’s mind by renouncing Right as its Supreme Law.”

It is interesting that Channing’s frame of the moral background to national wealth so closely refers to early 21st century economic malaise in America. Wealth which has accumulated contrary to the virtue of the nation, via empire, exploitation and greed, leads to negative outcomes. In other words, exploitative systems are fragile, unsustainable, and only benefit a few. So-called virtuous wealth is gained when a system is anti-fragile. Channing correlates his notion of virtuous wealth to a well-developed level of human capital, balanced institutions, a healthy distribution of wealth, and so forth. Even a consequentialist or a minarchist libertarian would agree that de-centralized economies with strong human capital are more likely to produce a better standard of living.

In Common Sense morality, virtue and consequence are harmonious concepts. That which is good is that which is natural and vice versa. Channing doesn’t propose a list of arbitrary moral precepts which must be followed. His morality requires that moral precepts must be continually adjusted to remain in harmony with natural consequences. Morality is the great End, but it is meant as a product of what is naturally right, and should contribute to what is naturally good.

After discussing the importance of putting morals before money, Channing discusses the dangers of doing the opposite. In doing so, he offers a stunning rebuke of policy wonkery and state economic intervention – over a century before public choice theory, and a half-century before laissez-faire economic theory.

“Let a people exalt Prosperity above Rectitude, and a more dangerous end cannot be proposed. Public Prosperity, General Good, regarded by itself, or apart from the moral law, is something vague, unsettled, and uncertain, and will infallibly be so construed by the selfish and grasping as to secure their own aggrandizement. It may be made to wear a thousand forms according to men’s interests and passions. This is illustrated by every day’s history. Not a party springs up, which does not sanctify all its projects for monopolizing power by the plea of General Good. Not a measure, however ruinous, can be proposed, which cannot be shown to favor one or another national interest. The truth is, that, in the uncertainty of human affairs, an uncertainty growing out of the infinite and very subtile causes which are acting on communities, the consequences of no measure can be foretold with certainty. The best concerted schemes of policy often fail; whilst a rash and profligate administration may, by unexpected concurrences of events, seem to advance a nation’s glory. In regard to the means of national prosperity the wisest are weak judges. For example, the present rapid growth of this country, carrying, as it does, vast multitudes beyond the institutions of religion and education, may be working ruin, whilst the people exult in it as a pledge of greatness. We are too short-sighted to find our law in outward interests. To states, as to individuals, Rectitude is the Supreme Law. It was never designed that the Public Good, as disjoined from this, as distinct from justice and reverence for all rights, should be comprehended and made our end. Statesmen work in the dark, until the idea of Right towers above expediency or wealth. Wo to that people which would found its prosperity in wrong! It is time that the low maxims of policy, which have ruled for ages, should fall. It is time that Public Interest should no longer hallow injustice, and fortify government in making the weak their prey.”

In summary, Channing says that people are stupid and planners never get it right. To base a government off of planning for the public good is to see plans fail, and in this vacuum, special interest assert itself. For this reason, governments are only really equipped to protect rights, and let the people use them to create the common good on their own. For Channing, morality is that which is common and clear.

What about pragmatism?

“Perhaps it will be replied to all which has now been said, that there is an argument from experience, which invalidates the doctrines of this section. It may be said, that human rights, notwithstanding what has been said of their sacredness, do and must yield to the exigencies of real life, that there is often a stern necessity in human affairs to which they bow. … [During a crisis] All rights are involved in the safety of the state; and hence, in the cases referred to, the safety of the state becomes the supreme law.”

If rights are conceded to the state, then the state’s self-preservation and self-serving interest are made supreme. If a crisis becomes too big for society to solve, it’s unlikely the state itself – with its coercive power – would be any better at solving it. When civil society faces a crisis, it seeks to save itself. If it fails to do so, it may turn to the state. However, the state would react in the same way – it will act to save itself. The state will not save civil society, if civil society itself gives up.

After his discussion of property, including how rights relate to humans-as-property, Channing devotes an entire chapter to rights themselves. This section is the most instructive of his treatise.

First, Channing defines rights as intrinsic to man’s nature as a moral being. As previously discussed, rights are not meant to be thought of as entitlements, but rather as instruments or abilities. He connects rights and duties as unified, co-dependent concepts. A basic conception of general rights can be used to deduce specific rights.

“Man’s rights belong to him as a Moral Being, as capable of perceiving moral distinctions, as a subject of moral obligation. As soon as he becomes conscious of Duty, a kindred consciousness springs up, that he has a Right to do what the sense of duty enjoins, and that no foreign will or power can obstruct his moral action without crime.

“The sense of duty is the fountain of human rights. In other words, the same inward principle, which teaches the former, bears witness to the latter. Duties and Rights must stand or fall together. It has been too common to oppose them to one another; but they are indissolubly joined together. That same inward principle, which teaches a man what he is bound to do to others, teaches equally, and at the same instant, what others are bound to do to him. That same voice, which forbids him to injure a single fellow-creature, forbids every fellow-creature to do him harm. His conscience, in revealing the moral law, does not reveal a law for himself only, but speaks as a Universal Legislator. He has an intuitive conviction, that the obligations of this divine code press on others as truly as on himself. … Accordingly there is no deeper principle in human nature than the consciousness of rights. So profound, so ineradicable is this sentiment, that the oppressions of ages have no where wholly stifled it.”

I have always felt that individualism is less selfish than collectivism. Individualism is not egoism. It, instead, perceives humans in general as having an individual existence. The implications of individualism to the self pertain also to all other human beings. An individualist who demands certain rights would also intrinsically accede those same rights to all others. Collectivists on the other hand, are quick to harm and hurt individuals in the name of a common good. The collective good is meant to benefit individuals, and yet, great harm to individuals is a frequent product of efforts to establish the collective good. Anecdotally, collectivist societies tend to be more superficial and face oriented. Charity is a phenomenon that applies when others are looking. Individualist societies tend to express charity even when no one is watching.

What are our rights? Channing offers an answer.

“Volumes could not do justice to them; and yet perhaps they may be comprehended in one sentence. They may all be comprised in the Right, which belongs to every rational being, to exercise his powers for the promotion of his own and others’ Happiness and Virtue. As every human being is bound to employ his faculties for his own and others’ good, there is an obligation on each to leave all free for the accomplishment of this end; and whoever respects this obligation, whoever uses his own, without invading others’ powers, or obstructing others’ duties, has a sacred, indefeasible right to be unassailed, unobstructed, unharmed by all with whom he may be connected. Here is the grand, all-comprehending right of human nature. Every man should revere it, should assert it for himself and for all, and should bear solemn testimony against every infraction of it, by whomsoever made or endured.”

Rights are related to the non-aggression principle. As stated at the beginning of this article, the value of human life is a product of an individual subjective assertion. Logically, all subjective assertion is equal, and so the value of all human life must also be equal. Our own promotion of our own and others’ happiness is a choice that is equally valid between all humans, thus we have a right to it, and also a duty to honor others’ right to it.

Channing also explains how this principle can lead to the derivation of specific rights, concluding with a condemnation of slavery for violating them.

“Having considered the great fundamental right of human nature, particular rights may easily be deduced. Every man has a right to exercise and invigorate his intellect or the power of knowledge, for knowledge is the essential condition of successful effort for every good; and whoever obstructs or quenches the intellectual life in another inflicts a grievous and irreparable wrong. Every man has a right to inquire into his duty, and to conform himself to what he learns of it. Every man has a right to use the means, given by God and sanctioned by virtue, for bettering his condition. He has a right to be respected according to his moral worth; a right to be regarded as a member of the community to which he belongs, and to be protected by impartial laws; and a right to be exempted from coercion, stripes, and punishment, as long as he respects the rights of others. He has a right to an equivalent for his labor. He has a right to sustain domestic relations, to discharge their duties, and to enjoy the happiness which flows from fidelity in these and other domestic relations. Such are a few of human rights; and if so, what a grievous wrong is slavery!”

A government or system which does not leave man free to pursue his own happiness has no moral justification. Moreover, not only must man be free, but specifically he must be permitted broad and particular freedoms which relate directly to that pursuit. The implication of freedom to pursue own’s own happiness is a set of uncountable shackles on government.

Channing describes the ideal government.

“That government is most perfect, in which Policy is most entirely subjected to Justice, or in which the supreme and constant aim is to secure the rights of every human being. This is the beautiful idea of a free government, and no government is free but in proportion as it realizes this. Liberty must not be confounded with popular institutions. A representative government may be as despotic as an absolute monarchy. In as far as it tramples on the rights, whether of many or one, it is a despotism. The sovereign power, whether wielded by a single hand or several hands, by a king or a congress, which spoils one human being of the immunities and privileges bestowed on him by God, is so far a tyranny.”

Democracy is not inherently good, and Channing explains why representative government even matters at all from the perspective of liberty – something American liberty lovers, and liberty lovers around the world ought not forget.

“The great argument in favor of representative institutions is, that a people’s rights are safest in their own hands, and should never be surrendered to an irresponsible power. Rights, Rights, lie at the foundation of a popular government; and when this betrays them, the wrong is more aggravated than when they are crushed by despotism.”

If a people lose the ability to withdraw consent from a governmental system, then that system is not consistent with liberty. The degree to which a government relies on voluntary consent rather than coercion, is the degree to which it is consistent with liberty. Wherever one stands on the spectrum of support for state power, this principle is true. A government can always be either more free or less free than it presently is simply by becoming less or more coercive in achieving its ends.

Conclusion

Channing concludes with his most powerful argument against the holding of men as property. He assumes, as always, the equality of men in determining for themselves what is right. However, he also injects his own aspirational hopes for how men should use their moral agency, as part of his subjective interpretation of what men are by nature. In contrast to modern day progressive politics, Channing’s desire for society to improve is based on hopeful aspiration combined with persuasion, through appealing to a common hope in equally morally sovereign fellow human beings. By emphasizing the moral sovereignty of human beings – himself counted among them – he obliterates any possible argument that defends slavery.

“I come now to what is to my own mind the great argument against seizing and using a man as property. He cannot be property in the sight of God and justice, because he is a Rational, Moral, Immortal Being; because [he is] created in God’s image, and therefore in the highest sense his child; because created to unfold Godlike faculties, and to govern himself by a Divine Law written on his heart, and republished in God’s Word.

“Into every human being God has breathed an immortal spirit more precious than the whole outward creation. No earthly or celestial language can exaggerate the worth of a human being. No matter how obscure his condition. Thought, Reason, Conscience, the capacity of Virtue, the capacity of Christian Love, an Immortal Destiny, an intimate moral connexion with God,—here are attributes of our common humanity which reduce to insignificance all outward distinctions, and make every human being unspeakably dear to his Maker.

“The capacity of Improvement allies him to the more instructed of his race, and places within his reach the knowledge and happiness of higher worlds. Every human being has in him the germ of the greatest Idea in the universe, the Idea of God; and to unfold this is the end of his existence. Every human being has in his breast the elements of that Divine, Everlasting Law, which the highest orders of the creation obey. He has the Idea of Duty; and to unfold, revere, obey this is the very purpose for which life was given. Every human being has the Idea of what is meant by that word, Truth; that is, he sees, however dimly, the great object of Divine and created intelligence, and is capable of ever-enlarging perceptions of Truth. Every human being has affections, which may be purified and expanded into a Sublime Love. He has, too, the Idea of Happiness, and a thirst for it which cannot be appeased. Such is our nature. Wherever we see a man, we see the possessor of these great capacities. Did God make such a being to be owned as a tree or a brute? How plainly was he made to exercise, unfold, improve his highest powers, made for a moral, spiritual good! and how is he wronged, and his Creator opposed, when he is forced and broken into a tool to another’s physical enjoyment!

“Such a being was plainly made for an End in Himself. He is a Person, not a Thing. He is an End, not a mere Instrument or Means. He was made for his own virtue and happiness. Is this end reconcilable with his being held and used as a chattel? The sacrifice of such a being to another’s will, to another’s present, outward, ill-comprehended good, is the greatest violence which can be offered to any creature of God. It is to degrade him from his rank in the universe, to make him a means, not an end, to cast him out from God’s spiritual family into the brutal herd.”

Channing exalts man’s consciousness of morality and hope, invoking what in my opinion is actually a double-edged sword of moral consciousness. A tree or rock has no happiness, no sense of purpose, no agency and consequently no rights. There is no inherent moral crime in chopping a tree or smashing a rock, nor do either protest. Humans, on the other hand, are quite upset when their lives are threatened, and tend to act aggressively to protect their own existence. Humans perceive a meaning to life, and the possibility of happiness. Nevertheless, the human desire to live and the human sense of happiness only exist within the human mind as a subjective assertion, and only matter because human will self-asserts the importance of human life. Take away the subjective human agent, and human life has no meaning. In other words, human life is meaningless until humans assert life’s meaning.

Philosophically, asserting meaning for life when that meaning is found only from within (and not out in nature), is an act of creation. In this sense, even a secular mind can appreciate the metaphor that man is in God’s image. Human action itself is an assertion of meaning, the creation of meaning – taking internal truth and attempting to externalize it. Human action is therefore sacred.

If human action is not sacred, then nothing on Earth can be sacred. Therefore, to take a man who is capable of divine action – the conception and pursuit of meaning – and deny him his own path to that meaning is a nullification of meaning itself. To say that a man cannot create meaning, is to admit that you yourself must also not be so able. To say that man creates meaning, but to deny him that right, is ugly sin.

The deeply religious should understand the meaning of man being in God’s image. Nature – creation – was born and will die, it is temporal, dust, and must fade. The goal of the religious is to seek both eternal life and union with God’s presence, and this goal is nothing short of aspiring to higher meaning that transcends that which is temporal or arbitrary. In philosophy, it is simply a quest to justify the idea that life is at least something more that totally meaningless.

Channing’s emphasis on religious, lofty sentiments is appropriate to his task. In arguing against slavery, he saves his best argument for last. Channing connects the lowest aspects of human nature to its highest. He proves that the conditions which might justify moral coercion cannot exist. Though many humans are brutish, ignorant, low and so forth, they possess a spark of awareness that objects and creatures do not.

Humans perceive meaning to life and seek out the fulfillment of life’s purpose. This connects them automatically to the highest possible aspirations any mere man could conceive. While the ignorant might not consider lofty philosophy in their daily choices, nevertheless, there is nothing that the greatest philosopher or sermonizer could invoke that is outside of the scope of what the lowest man can connect with. The implications to morality are clear. Men are equal.

The simple way of summarizing Channing’s argument is to say that human life is sacred. Life includes the individual perception and pursuit of life’s meaning, since it is individuals who self-endow their lives with a sacred character. The desire to live is all it takes. Likewise, the desire to be free is all that is required for a man or creature to deserve freedom. It’s a take-it-or-leave-it proposition for anyone who asserts their own freedom.

Any slaver or government which denies the human desire for freedom and moral independence, denies the fundamental value of human life. Human life becomes arbitrary. That’s no way to go.

It is interesting that Channing, in arguing against slavery by invoking moral principles, so often digresses through the same reasoning to rebuke what is now called progressive politics. Libertarians should come to understand that the same moral reasoning which argues against slavery also argues against progressivism. By the same logic, progressive morality ultimately could justify slavery. The progressive opposition to slavery lies entirely with an inconsistent and logically detached appeal to empathy, focusing on the subjective pain and distress felt as part of the experience of being a slave. If, then, slavery could facilitate the comfort and pleasure of the slaves, would progressives support it? The answer must be yes.

Progressivism is slavery exactly, if we imagine a non-existent world where slaves, by having their material needs taken care of, were consequently happy. Yet, there’s a reason why slaves experienced physical pains and emotional distress, which is intimately connected to the moral nature of slavery. As discussed at length in this article, moral self-sovereignty is the right to pursue happiness no more nor less. Abandon that principle, and power inequality will, through violence and accidental outcomes, develop systems of exploitation where happiness is crushed. Whether we observe this in systems of slavery or within communist states, it is the same. Progressivism is merely the first step on the path.

In understanding rights, libertarians perceive an important truth. With is and ought reconciled inside the individual, the common truth of society is clear. Economic action services moral action. Moral action is sacred, inviolable. This is should be the basis of libertarian thought, and the guiding principle of human society.