The most important question for asset prices right now, from stocks to houses to Bitcoin, is whether we’re due for a recession. Last week we got confirmation that according to the traditional definition of a recession—two quarters of negative growth—we are already in a recession.

The response from this administration has been denial and word games rather than actually trying to stop the slide. At which point the betting shifts to whether it’ll be a shallow 1991-style recession or a big, 2008-style one, perhaps with a financial crisis to spice things up.

Bigger-picture, what we’re seeing is a concentrated version of the world that paper money delivers: an endless series of booms, busts, and financial crises, all to sustain a permanent siphon of the peoples’ wealth towards subsidizing federal deficits and Wall Street-brokered leverage. Millions are waking up to what fiat money does, which could be bullish for Bitcoin in the long run.

The Numbers

First, the GDP numbers. Going by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), real GDP shrank at an annualized rate of 1.6% in Q1 and then dropped another annualized 0.9% in this most recent Q2. GDP is revised several times through the quarter, so that could change for better or worse. Meanwhile, of course, if they’re under-estimating inflation, as many believe, then the real decline could be much worse. Perhaps on the scale of a 3% annual drop in GDP.

To put that in perspective, in 2008 real GDP shrunk 1.6% in the first bad quarter (Q1 ’08), then rebounded to plus 2.3% in Q2 before falling to -2.1% in Q3. So, just reading the numbers, we’re in a substantially worse spot at the moment than 2008, even if we believe the inflation numbers.

By the way, about those definitions, the administration correctly claims that the private economics outfit NBER has the final say on what’s a recession. The problem is that over the past 75 years the NBER has never failed to call two down quarters a recession. Rather, they’ve only used their discretion to call a zig-zag a recession, as in 2008. So NBER only calls it worse, never better than the two-quarter standard. Why the chicken-little NBER is suddenly dismissing falling boulders is a very valid question, but then you probably already know why.

How Long will the Pain Last?

So where to next? Given the Fed is openly engineering a recession in order to slow inflation, the key question is whether inflation comes down on its own or will the Fed try to engineer harder.

Now, to be fair, inflation could come down to some degree. After all, if you shut down half the economy worldwide, there will be some hiccups along the way. Considering there’s little public appetite for new lockdowns and Ukraine is settling into a slog, barring a still-unlikely Chinese escalation over Taiwan things should continue ironing out.

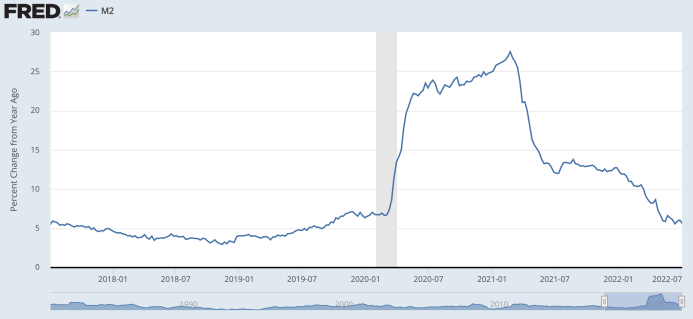

Indeed, money printing is settling down to more normal rates: Over the past year, money supply in M2 has grown 5.6%, similar to the Obama and Trump eras. That’s down from 25% in the first year of the pandemic and 11% in the second year.

So the main driver of inflation—federal spending—is easing.

Of course, that doesn’t mean the pain is over; inflation famously lags money supply, typically around 18 months. And M2 growth has only recently calmed down. Meaning money could continue driving high inflation for, going by history, another 16-odd months.

At the same time, the slowing economy itself will probably start slowing inflation via “demand destruction”—fewer people buying less stuff. Indeed, that’s the Fed’s goal in driving higher rates, to choke off the private economy. But the question is will private demand come down a little or a lot? Literally, nobody knows—as so often in economics, we’ve never had precisely this sequence of economic shocks, so we can only guess from history.

By the way, a few weeks ago I did guess based on history, and the punchline is it gets ugly depending on the comparables, but nobody knows which will happen. Indeed at a recent conference in Europe, Chairman Powell himself remarked, “We now understand better how little we understand about inflation.” Invites the question of why he didn’t resign on the spot. But underlining that nobody knows how fast inflation will fall—if it falls at all—and how much of the economy it takes down with it.

Of course, this “demand destruction” is up against the shrinking economy itself. That is, if the real economy is shrinking because of Biden’s War on Production or because new climate or race mandates are imposed on the economy, then inflation rises simply because there’s less stuff being produced.

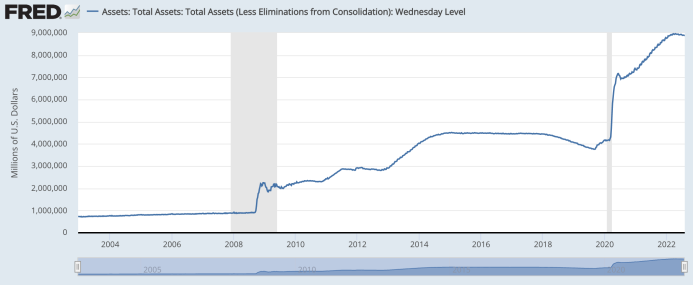

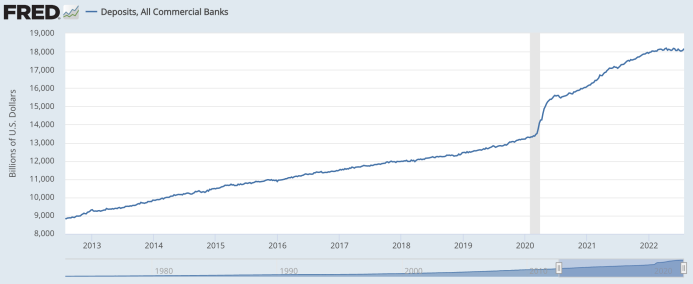

Finally, I think the biggest unknown on inflation, hence on GDP’s future path, is what happens to the giant lump of fresh money that was pumped out during COVID—indeed, almost $5 trillion. Much of that new money isn’t showing up in inflation yet because it remains stashed in bank accounts. It’s stashed either because people didn’t need the free money and saved it, or because they saved up as a cushion during the scary times of COVID.

Effectively, all that money has been buried in the backyard in terms of inflation—it’s not for sale. But once those bank accounts start to empty, which should happen both as Covid fears recede and as the economy slows, all those frozen trillions are released into the wild to go chase a now dwindling pile of goods, giving inflation a second wind. You can see in the chart below it’s just starting to trickle out, with much more to go.

So, in sum, the main drivers of inflation these past two and a half years are fading, but most of that fresh money is still locked up. So we could still have a long period of elevated inflation. And, if we do, the Fed could continue panic-hiking into a serious recession or even a financial crash.

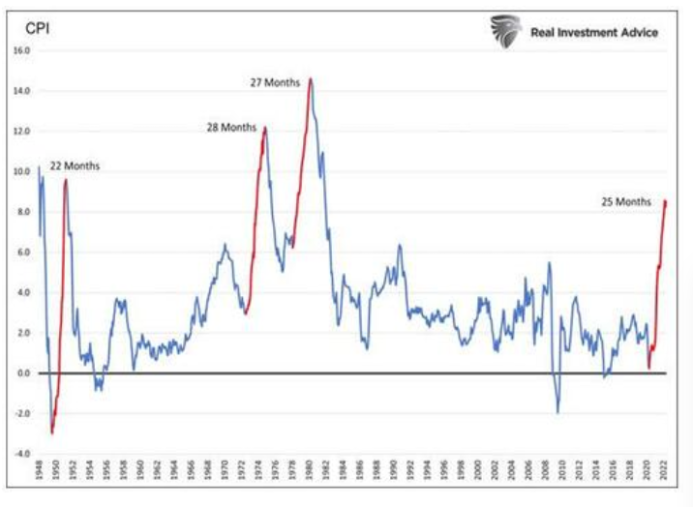

One interesting Zerohedge chart this week noted that bouts of high inflation tend to last two and a half years before coming down. Which would put us at another year or so of pain. Of course, that two and a half year cycle doesn’t drop from the sky; it’s driven by the central bank itself reacting to bad numbers and jacking rates, noting that lag between M2 and inflation.

Having said, the orgy of money printing these past two years has been substantially higher even than the “Great Inflation” of the 1970’s—it turns out it took a lot of trillions to tranquilize the population into accepting lockdowns. So the magnitudes are likely to be larger, or the timelines longer, than what we’ve seen since the 1950’s.

Recession: How Long and How Deep

The shape of recession will be a question of how those four inflation factors (slowing M2, fading COVID, falling production, draining savings) impact Fed rate decisions, which in turn either crash harder or soften the blow.

If inflation does come down a lot due to those four factors (“on its own” is how the news will frame it), then the Fed will pause or reverse hikes, and we’ll probably limp along like the Obama years. That is, government will continue to excrete new economy-hobbling regulations and taxes, but the economy will be able to handle it, cleaning up the messes as quickly as government makes them.

Indeed, that’s the going bet on Wall Street, with current projections for positive but fading GDP growth the rest of this year and 2023, ending next year at 1.3% real growth—pathetic, but not a 1970’s-style catastrophe.

So that’s the best case: we coast like a car that’s run out of gas, slowing gradually until either a new administration reverses course or until enough economic deadwood has been cleared that the economy turns back to growth.

And if inflation doesn’t come down “on its own?” Then the Fed, after its habitual several quarters of denial, gets back to economy-crushing hikes. Ushering in a potentially severe recession.

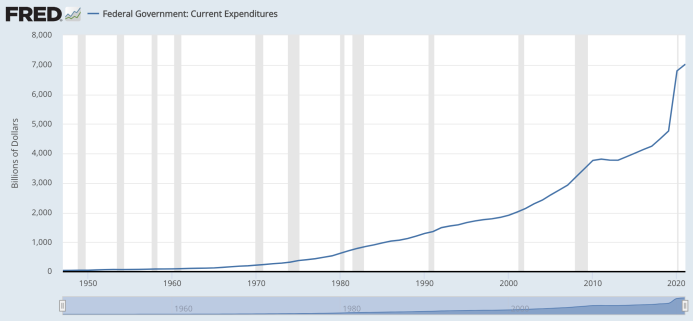

Of course, there is an out-of-box solution, which is to end inflation by dramatically lowering federal spending. Simply getting back to pre-COVID could drop federal spending by some $1.5 trillion per year, while getting back to a Bill Clinton-scale government drops more like $4 trillion every year. We’d have the debt paid off in a decade.

Trimming a couple trillion off federal spending would indeed tame inflation for decades to come. But then you’d have to be pretty naïve to think this administration and Fed will go that path.

So that leaves the most likely stubborn-inflation scenario: Fed pretends it’s not there for a while, then crashes the economy so We the People get to, once again, tighten our belts.

So, bottom line, it’s a recession at the moment; whether it gets worse depends on inflation, and policymakers goofing around whistling past graveyards should give anyone pause.

This article was originally featured at Peter St. Onge’s substack CryptoEconomy and is republished with permission.