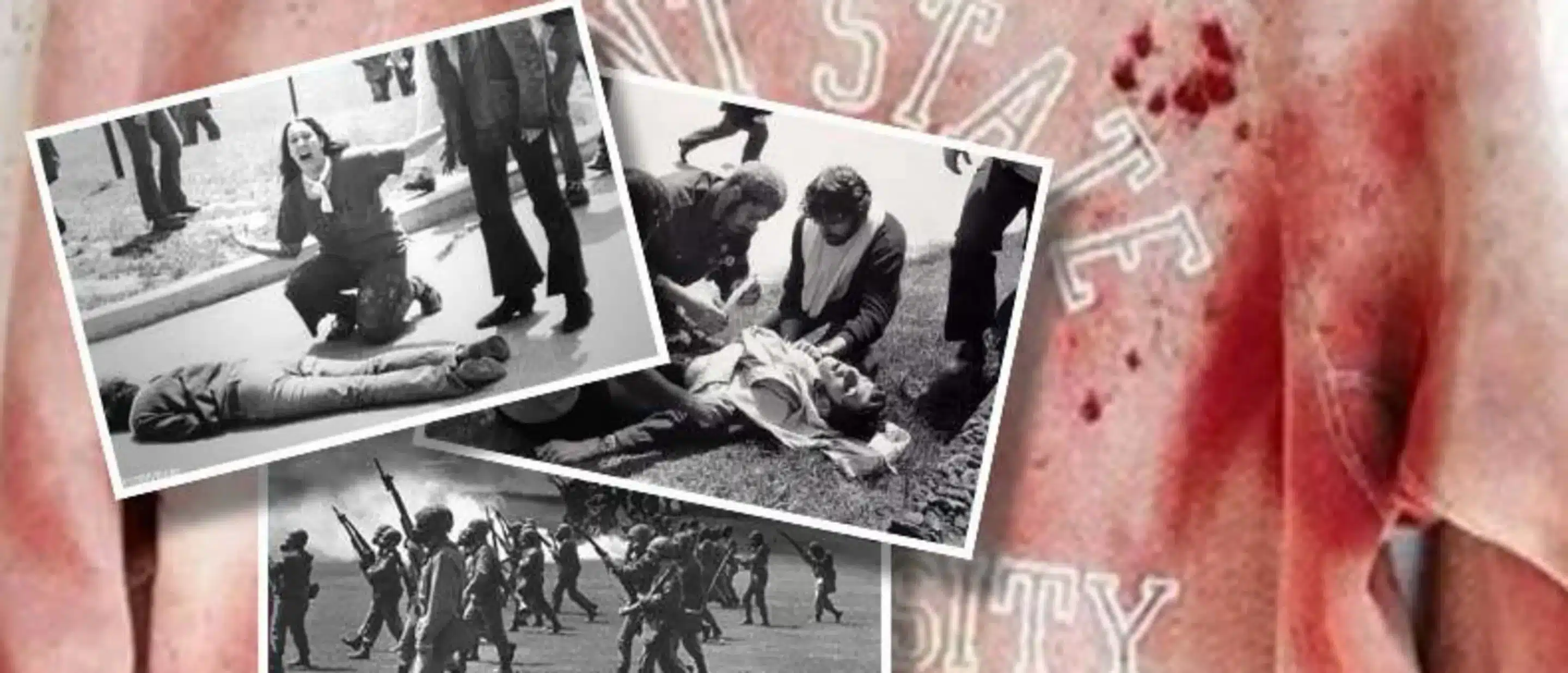

On May 4, 1970, a disorganized and nonviolent antiwar protest turned violent and deadly when the Ohio National Guard inexplicably opened fire on students at Kent State University—indelibly polarizing the United States populace to an extreme arguably unabated since.

Guardsmen opened fire on the assembled crowd, unleashing between 61 and 67 bullets in 13 seconds—which left four people dead and nine wounded. Now, 49 years after the unjustified bloodbath, critical questions remain unanswered about both details of the incident, as well as circumstances that culminated in the shooting of unarmed protesters.

Perhaps the only inarguable detail of the Kent State massacre, often referred to simply as “Kent State,” is the fundamental, polarizing shift in popular perception.

The younger generation epiphanically concluded that the constitutional right to speak against a government amounted to a hollow promise—and that same government harbored no qualms in deploying violence to quash such dissent. But that same generation of young people, generally under 30 years old, also witnessed their parents’ and the older generation’s acceptance of—and, often, prideful approval of—that exact violence by the National Guard.

Inaccurate propaganda worked brilliantly to the government’s advantage—both before and after the shootings—cleaving false divisions between the ‘dirty hippies’ and ‘ordinary’ Americans. Families of the dead and wounded received abhorrently telling letters in the weeks following.

Among the dead was an ROTC student-athlete who—evidencing the randomness of the shooting—had nothing to do with protests and happened to be caught at the wrong place at the wrong time. His parents received a letter, cited by The Bulletin, calling their son a “destructive, riot-making communist”—and they should “be thankful he is gone.”

Soldiers at Quantico Marine Base, The Bulletin reported, erupted in cheers when someone wrote, “Kent State 0, National Guard 4” on a chalkboard.

Shocking as those reactions to the killing of unarmed, peaceful protesters might be 46 years removed from that day, elements of division in the U.S. populace residually still affect the political climate.

As many activists observe, society-at-large tends to scoff at activity on which the roots of so-called American democracy was founded—dissent against the unjust—particularly when the injustice is effected by the government. It’s likely such misunderstanding and mischaracterization of what makes for a healthy, democratically-modeled system began in earnest in the turbulent 1960s, solidified with the Kent State massacre, and emphatically continues today.

Protests at Kent State prior to the shootings were debatably spurred by President Richard Nixon’s announcement on April 30 about the expansion of the already-highly contentious Vietnam War into neighboring Cambodia. But, contrary to reports, outside agitators were not involved and angry protesters did not torch the ROTC building on the Kent State campus—a matter of no little significance, considering the Guard was only present to protect the burned-out building. Indeed, its torching has inexplicably been claimed as justification for the shooting.

Dean Kahler, an undergraduate at Kent State who was shot and paralyzed in the incident, explained in an interview with NPR the oft-touted idea students had torched the ROTC building has “always been one of the misconceptions. The Justice Department and the President’s Commission on Student Unrest basically said that the students didn’t burn the building down. It was burned down by someone who knew how to burn building[s] down.

“At the time the building burned down, there were virtually no students at the site. The building was totally surrounded by campus security and local police authorities. And so there was really no reason to assume that the students burned the building down. It’s one of the myths of the burning of the ROTC building.”

Another misconception, similarly proffered at the time as justification for the Guard to shoot, was the fiction the students had shot first. In fact, no one in attendance at the rally had firearms—and none expected the calm assembly to turn violent. So much so, even once guardsmen opened fire, most believed they were firing blanks—the idea of unleashing live bullets on a crowd whose greatest offense was profanity seemed so ridiculous, many couldn’t come to terms with seeing the dead and wounded.

Though there have been sparks and lulls in political polarization since the Kent State shootings, the incident’s epiphanic moment solidified national identity in two starkly contrary directions.

On one side, the pro-government nationalists generally willing to support authority for its own sake stood in unwavering support of the National Guard. On the other stood those questioning the event—a widely diverse counterculture who not only view patriotism for the sake of patriotism as hollow absurdity, but who also abruptly realized the necessity in questioning the governmental narrative and paradigm.

One pertinent question should come to mind, though, for people of either stance: why does government continually and only valorize the deaths of those who perish at the hands of civilian criminals, while either excusing or ignoring the value of lives lost to criminal acts by government agents?

Mass schoolshootings or apparent terrorist shooting sprees almost inevitably precede tears from the president and seeming noble calls for strict gun control to rein in the violence. But criminally negligent and wholly unjustified killings by law enforcement—both in the U.S.’ current epidemic of police violence and in the example of Kent State—undoubtedly receive no such call.

Hypocrisy, even absent of words, can be enormously telling.

Whatever revelations May 4, 1970, managed to codify, humans maintain a startling tendency not to learn from the past; and, in fact, to frequently err in similar ways. With that in mind, 2023 marks a similar conflagration of competing political theories espoused by competing politicians, all parroted by disenfranchised voters—with underlying policies once again seeking to quash dissent.

“What could possibly go wrong?” you might ask.

On the anniversary of the day ‘war came home,’ it’s pertinent not to forget one answer: Kent State.

This article was originally featured at The Free Thought Project and is republished with permission.