“Poverty has no causes; prosperity has many. As history attests, poverty is humanity’s default condition…. But prosperity is not natural; it does not just happen.”

—Phil Gramm and Donald J. Boudreaux

To hear some people tell it, America is in the grip of a vast conspiracy in which billionaires get richer, the middle class stagnates at best, and the poor get poorer. Poverty and inequality, by this account, are the shame of America. How can we let this go on!

Do not fall for it. Except for the part about billionaires (those who get rich by innovatively serving consumers), the story is hokum. The middle class shrinks because its members move up, and the “poor” get richer with mass production and lower prices. If a monolithic predatory ruling class has been making war on the rest of us, it has been bloody bad at it. Do you need proof (besides the abundant evidence in your home and out the window)? Check the data! This doesn’t mean all is well with the American political system—far from it. Rather, it means that the market economy and the freedom it entails can take a licking and keep on ticking—better and better as years go by. Free the market (that’s us) of government shackles, including Trump’s tariffs, and the pace of wealth creation for all will quicken.

Phil Gramm and Donald J. Boudreaux document the real story in their book, The Triumph of Economic Freedom: Debunking the Seven Great Myths of American Capitalism. Let’s see what they have to say about poverty.

Admittedly, the officially released statistics are a downer. Data compiled by many prestigious-sounding agencies and organizations, Gramm and Boudreaux write, “show that a higher percentage of Americans live in poverty than in any other developed country in the world.” If true, that might be a mark against a commercial society like the United States. (Then again, it might be the government’s fault.) “All of these damning conclusions,” the authors continue, “are buttressed by the US Census Bureau’s official measure of poverty, which shows that the poverty rate has not declined on a secular basis for more than fifty years.”

That stinks, but is it so? Actually no.

Gramm and Boudreaux, both economists, show that from 1947 to 1967—before the Great Society got into gear—the U.S. poverty rate dropped by over 50 percent. So “It seems strange that … when the War on Poverty began and its programs were funded at significant levels, beginning in 1967, the poverty rate then remained essentially unchanged for over a half-century.”

That is strange, especially because “the average bottom-quintile household has seen the inflation-adjusted value of government transfer payments rise from $9,700 per year in 1967 to $45,400 in 2017….” (That excludes the administrative costs.)

“Obviously,” they write, something is wrong here.”

What could be wrong? How about this? The data leave out quite a few important things.

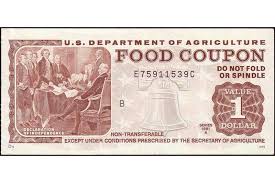

[T]he official Census measure of poverty fails to count 88 percent of all the benefits that poor American families receive from the government as part of their income.” [Emphasis added.]

Eighty-eight percent!

The omitted benefits include “refundable tax credits where the beneficiary receives a check from the Treasury, debit cards loaded with food stamp allowances, and benefits from over a hundred other major programs, including Medicaid and housing subsidies in which the government simply pays bills that are incurred by the programs’ beneficiaries.” (This curious practice of omitting benefits is left over from when government benefits were mainly in cash.)

How do things look when that data is restored? Gramm and Boudreaux write, “When all transfer payments, net of the costs of making those payments, are counted as income to the recipients of the transfers”:

- The 2017 overall poverty rate drops from the official 12.3 percent to 2.5 percent;

- The child poverty rate drops from the official 17.5 percent to 3.1 percent; and

- The poverty rate for seniors drops from the official 9.2 percent to 1.1 percent.

Gramm and Boudreaux account for the small percentages remaining by people who “have fallen through the cracks” because of medical and other problems. In any society, no matter how rich, some people choose poorly. The authors cite other studies that support this adjusted overall poverty rate.

Moreover, Gramm and Boudreaux point out that “the number of people who are classified as poor changes dramatically over time.”

Less than a quarter of families classified as being poor have been poor for two years or more. It should also be understood that twice as many families were poor for only some part of the year as those families who were poor the entire year. Experiences such as being laid off, suffering illness, or being employed in seasonal work contribute to people alternating between being on the poverty rolls and rising off of them.”

The misleading official picture, Gramm and Boudreaux note, is also exposed by the fact that, according to a different Census Bureau study, “42 percent of poor households own their own homes, the average of which has three bedrooms, one and a half baths, a garage, and a porch or patio. Of the households considered to be poor, 88 percent have air conditioning, and the average poor American family lives in a home that is larger than that of the average middle-income family in France, Germany, and Britain.”

And this is impressive: “Of all American households in 2017, 66.3 percent had real incomes, after transfers and taxes, that only the top 20 percent enjoyed in 1967.” That hardly looks like stagnation.

Does this mean the welfare state works? Not if the goal is to foster independence in lower-income people. But the data do tell us that the welfare state does not need expanding, as the progressives claim.

For one thing, it discourages people from working and thus encourages dependence on the coerced taxpayers. Gramm and Boudreaux write,

The explosion in poverty benefits since 1967 caused the prepandemic employment rate among the bottom 20 percent of income earners to plummet from 67 percent to 36 percent, as well as the employment rate among the second quintile of earners to fall by almost 6 percent…. The growth in the welfare program has largely delinked the bottom 20 percent of income earners from the American economy….

It is not good when working people in the second lowest quintile have only slightly higher incomes than those who work little or not at all.

What’s unseen is that without the welfare state, not only would the incentive not to work disappear, but the most innovative and productive people would have more money with which to make everyone more affluent.