Farm exports to China are down, manufacturing job growth has stalled, and prices are up for many goods

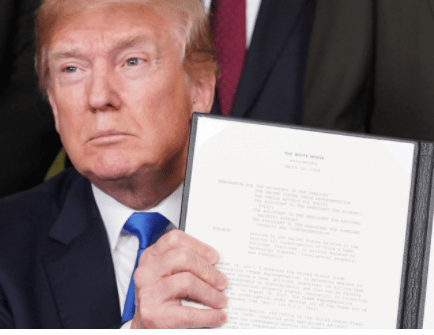

Americans are about to enter the third full year of President Donald Trump’s aggressive tariff regime, which aims to promote US manufacturing, protect key industries, and prompt other nations to reduce their trade barriers. So, it’s a good time to stop and ask whether tariffs are producing the results desired by the president and other supporters of his trade policies.

It’s an important question for America’s economic future as well as for the president’s reelection chances. But with ongoing trade talks with China and other countries producing little real progress and the recently negotiated US, Mexico, Canada Agreement (USMCA) to replace NAFTA stalled in Congress, the best that can be said for the president’s trade agenda is that it is a work in progress. The more sober reality is that actual results have been sparse, and the damage to trade flows and economic activity has been real and painful for American consumers, manufacturers, and farmers.

Candidate Trump ran in 2016 as a critic of post-war US trade policy, which has emphasized trade agreements to incrementally lower barriers in the United States and abroad. For years, the president has blamed those policies for the loss of millions of manufacturing jobs and the rise of the US trade deficit, most acutely with China.

Once elected, President Trump immediately withdrew the United States from the Transpacific Partnership (TPP), the deal negotiated under Barack Obama’s administration to liberalize trade with 11 other Pacific Rim nations. Then, starting in January 2018, his administration imposed tariffs on imported washing machines, solar panels, steel, and aluminum, launched a tariff war against China under Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974 over intellectual property, and negotiated a new version of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA)—now dubbed the US-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA). Along the way, his US Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer also revised the 2011 free trade agreement with South Korea (KORUS) and struck a limited deal with Japan on digital trade (which includes industries such as e-commerce and cloud services) and farm tariffs.

The centerpiece of the Trump trade policy has been China. In an effort to force the Chinese to improve their policies on intellectual property protection and foreign investment in China, the administration began imposing escalating rounds of duties on imports from China in July 2018. Currently, those duties range from 15 to 25 percent on $362 billion in imported goods from China, with duties on another $160 billion scheduled to kick in on December 15. Meanwhile, the Chinese have imposed retaliatory duties on $75 billion of US exports.

To date, China has implemented none of the reforms that the Trump administration demanded. China has announced further liberalization of its rules on foreign direct investment, but those changes were in the works before the US tariffs were imposed. China also recently lowered duties on a range of goods, but only for imports from its non-US trading partners, putting US exporters at a disadvantage relative to their global competitors. President Trump and his defenders claim that his get-tough approach has forced China to negotiate, but so far those talks have led to no agreement, and could break down once again.

Meanwhile, mounting evidence suggests the tariff war is taking a toll on US exporters, especially US farmers who have lost one of their best global customers for soybeans, pork, and dairy products. Farm exports to China, which peaked at more than $25 billion a year under President Obama, have tumbled to less than $10 billion in the past year. US manufacturing companies have suffered the double whammy of losing exports while being forced to absorb higher costs from duties on imported parts from China. Prices are rising for the millions of American families that buy such imports as furniture, clothing, and electronics from China. In sum, the Trump administration’s China policy so far has been all pain and no gain.

Another priority of the president’s trade policy has been the renegotiation of the quarter-century-old NAFTA. The president has repeatedly denounced the 1994 agreement as the worst trade deal in history, blaming it for a huge loss of manufacturing jobs and output to Mexico (claims that are certainly open to dispute).

Despite the president’s criticism, the renegotiated agreement signed a year ago, the USMCA, leaves the core of NAFTA intact. It keeps almost all tariffs at zero, removes some lingering barriers to farm trade, and tightens the rules of origin for the automotive sector, while adding chapters on such subjects as digital trade, labor, and the environment.

The agreement still needs congressional approval, but if and when it is passed, its impact will not be nearly as dramatic or as positive as the Trump administration claims. An analysis by the US International Trade Commission (USITC) in April 2019 estimated that once fully enacted, USMCA would boost the US economy by $68 billion, or 0.35 percent of GDP, and add a net 176,000 jobs (a rounding error in an economy that employs more than 150 million workers). All that gain would come from the new agreement reducing uncertainty, specifically in digital trade.

At the same time, according to the USITC, a big net negative of USMCA will be its tighter rules of origin for auto makers. The new rules will increase the share of parts that must be sourced in North America to qualify for duty-free treatment to 75 percent, and mandate that 40 to 45 percent of those parts be made by labor earning at least $16 dollars an hour—which would disqualify production in Mexico. The USITC report determined that the tighter auto rules “represent greater restrictions on trade.” Those rules will result in higher production costs for the car industry, especially for smaller, more fuel-efficient models, which in turn will lead to reduced exports, higher prices and less choice for consumers, 140,000 fewer vehicles sold each year in the United States, and reduced wages and employment in the overall US economy.

Ironically, many of the new features of the USMCA were contained in the TPP, which included Canada and Mexico and was therefore already a retooled, 21st century NAFTA 2.0, without the trade-restricting baggage of the tighter rules of origin for auto production. Far from being a breakthrough on trade policy, USMCA accomplishes little that would not have been included in TPP and will leave the US auto sector less competitive in global markets.

Meanwhile, steel tariffs delivered an early boost to the domestic US steel industry, but that glow is now fading. The higher domestic steel prices imposed by the tariffs hurt the much larger sectors of the economy that use steel in production, from construction to the auto industry. Those higher prices dampened domestic demand, which in turn has caused a drop in steel prices and sales for domestic steel producers. After initially ramping up production, domestic steel companies have been reducing output and laying off workers, exactly the opposite impact the administration hoped to achieve. Meanwhile, the tariffs have prompted retaliation by the EU and other trading partners against US exports.

The Trump administration did muscle South Korea into renegotiating sections of the 2011 US-Korea free trade agreement, known as KORUS. Under the threat of steel tariffs and US withdrawal from the agreement, USTR forced Korea to agree to delay the elimination of the 25 percent duty on light trucks imported to the United States and to agree to double the Korean quota on American vehicles that can be imported to Korea without meeting its tougher safety and emissions standards.

The export quota was never fulfilled, so doubling it will not likely lead to a major increase in US exports to Korea. The delay in reducing the light truck duty is a win for domestic US automakers, who depend on the sale of these vehicles, notably pickups, for a sizable share of their annual sales and profits. But (like the tighter auto rules of origin in USMCA) the delay means that pickup prices in the US will be higher than they would be otherwise.

More recently, the Trump administration applied the same type of pressure on Japan, prompting that country to accept an interim agreement to reduce its barriers to US farm exports while adopting new rules on digital trade. The reduced farm trade barriers would be a clear win for US producers, but they are not quite as good as the farm trade liberalization measures that are contained in the TPP, which also included Japan. Like KORUS and USMCA, the Japan agreement involved a lot of brinksmanship during negotiations with no clear gain, compared to the status quo if the United States had joined the TPP.

The net result of the Trump trade policy so far has been an upward spike in tariffs imposed on both US imports and exports and downward revisions of global economic growth. The International Monetary Fund and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development have both downgraded their growth forecasts, blaming the US-China trade war and the resulting uncertainty as the main aggravating factors. Even President Trump’s own economic advisors warned him recently that the trade war with China is proving to be an economic and political liability.

The US labor market continues to perform well, but that’s despite and not because of the president’s trade policy. Job growth has actually cooled since the trade war began in earnest last summer, especially in the manufacturing sector. In the first 18 months of the Trump presidency, according to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, manufacturing employment was growing at an average of 19,000 jobs per month. But that rate has dropped to only 4,000 so far in 2019 (even excluding the impact of the GM strike). Moreover, growth in US industrial output has slowed sharply in recent months.

Even President Trump’s favorite scorecard, the US trade balance, has moved toward an even larger deficit under his policies. Two of his top trade advisors, Peter Navarro and Wilbur Ross, wrote during the 2016 campaign that reducing the trade deficit would be a key component of his program to stimulate the US economy.

Yet the deficit has only grown under his watch. The goods deficit in 2018 was $887 billion, 18 percent larger than the $751 billion deficit in the last year of the Obama presidency. Through September 2019, the deficit is on pace to be even larger, at nearly $900 billion by year’s end.

Almost all economists will tell you this isn’t a real problem, but it challenges the Trump administration’s assumption that raising US tariffs will somehow “level the playing field” and bring down the trade deficit. The bilateral deficit with China has shrunk, but imports have merely been diverted to other suppliers, leaving the overall deficit unaffected.

On rare occasions, President Trump has said that his ultimate goal is a world without trade barriers or subsidies. But more frequently, the president has praised the beneficial impact of tariffs, describing himself famously as “a tariff man.”

By this standard, his trade policy has been a success. Through September, the amount of money the government collects through tariff duties is, year to date, running 70 percent ahead of 2018, and will likely top $80 billion by the end of the year. That’s almost a $50 billion tax increase compared with the average of $31 billion in duties collected before the president launched his tariff crusade.

This is an odd boast for a Republican president. Tariffs are taxes on tradeable goods. They disrupt production, raise business costs, and hit consumers in their pocketbooks—especially lower income families that spend a higher share of their budgets on imported items such as shoes, clothing, and food. All major studies done of the recent tariffs show that it is US importers and consumers who are paying almost all of the cost of the new duties. For US workers, those higher prices mean lower real wages.

With less than a year to go before the next election, President Trump’s trade policy must be declared a spectacular and expensive failure. A few incremental promises of more market access abroad have been overwhelmed by huge tariff increases in the United States as well as among our major trading partners. For the good of American workers and producers, as well as his own political legacy, President Trump should find a way to wind down his endless trade wars and return the United States to the proven path of post-war trade liberalization.

Reprinted from the Mercatus Center.