Let’s … Be Careful Out There (Very Important Update, 11/28)

Vancouver, B.C. October 14:

Canadian police swarm 40-year-old Polish expatriate Robert Dziekanski and electrocute him to death with Taser International’s renowned “non-lethal” implement of torture.(For the November 28 update, see the bottom of this essay.)

The kind folks at Taser International, makers of the eponymous portable torture device that is rapidly becoming notorious for its overuse by police, maintain a charitable foundation for the families of police officers killed in the line of duty.

On November 19, the makers of the reliably lethal “non-lethal” stun gun donated $500,000 to the Taser Foundation for Fallen Officers. This is sofa-cushion change for a company that saw its profits double during the third quarter of this year, surging to $28.5 million on the strength of a bull market, both domestically and internationally, for implements of State coercion.

Coercion through individualized torture is Taser’s business, and that business is booming.

“We lose an average of 145 officers per year and the Taser Foundation provides immediate financial support to these families during terrible times of crisis,” explains Gerry Hills, the Foundation’s executive director.

(Continues after the jump)

From Sci-Fi to Street Reality: In the Nazi-like “Mirror Universe” of Star Trek, personnel carried a Taser-like device called an “Agonizer,” which was used to administer instant punishment to inept or insubordinate personnel. Go here (at about 1:13) to see the sci-fi device used against a fictional character. Go here and here to see the real thing used needlessly against living human beings.

See the video below for an account of the death of an elderly, wheelchair-bound, schizophrenic woman through Taser torture at the hands of police:

Providing for bereaved families of fallen police is a worthy undertaking. But if Taser executives were acting out of genuine altruism, rather than cynical corporatist calculations, they would create a similar fund to aid victims of illicit police violence and their traumatized families.

There’s little doubt that police work can be a dangerous occupation, and that it is often a thankless one for those attracted to it by an honorable desire to protect the innocent. Not to put too fine a point on the matter, individuals of that sort are not over-represented in today’s “law enforcement” community.

And as I’ve pointed out before, the role of police officers today – whatever it had previously been – is not to protect the public, but to enforce the will of the State: Police officers are not legally or civilly liable to provide protection to individual citizens, but they are required to enforce the State’s mandates, however asinine or corrupt they may be. This is why, in my view, episodes of genuine police heroism in defense of the innocent are worthy of celebration – well as careful examination with an eye for the counter-intuitive finding.

Consider the paradigmatic case of police heroism, that of the officers who raced into the stricken World Trade Center towers on 9-11. Like most people, I cannot imagine dashing into a building I know faces imminent collapse in order to rescue strangers. The heroism of the 23 NYPD officers who died at Ground Zero is genuine, and isn’t diminished one whit by the fact that they were “just doing their jobs.” The same can be said of the firefighters and rescue workers who likewise perished while trying to save the lives of others.

Admirable and inspiring as it is, this example of authentic police heroism in the face of lethal violence is entirely unsuited as a symbol of routine police work. Most police officers – “most” in this case being a term that leaves the smallest quantum imaginable as a remainder – will serve out their careers without being exposed to anything resembling the mortal danger faced by the brave NYPD officers who died on 9-11.

That’s because police work simply isn’t that dangerous.

As Forbes magazine noted in late 2002, the atrocity at Ground Zero dramatically skewed data on workplace fatality rates collected each year by the Labor Department’s Bureau of Labor Statistics through its “Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries.” In “a normal year, like 2000,” explained Forbes, “the most dangerous jobs do not involve firefighting or police work; they involve cutting timber and fishing.”

In an essay drawing on the most recent BLS findings, David R. Butcher of Industrial Market Trends compiled the following roster of the ten most dangerous U.S. occupations:

*Fishers and Fishing Industry Workers, whose fatality rate was 142 deaths per 100,000 workers;

*Pilots and Flight Engineers, particularly crop dusters, test pilots, and chopper drivers (88/100,000);

*Loggers (82/100,000);

*Iron and Steel Workers (61/100,ooo);

*Refuse and Recyclable Material Collectors (42/100,000);

*Farmers and Ranchers (38/100,000);

*Electrical Power Line Workers – Installers and Repairers (35/100,000)

*Roofers (34/100,000);

*Drivers – truckers or sales personnel (27/100,000);

*Agricultural Workers (22/100,000);

One arresting aspect of this list is the fact that not a single one of the most dangerous occupations is a “public” sector job. Some of them (such as garbage collectors and test pilots) might work for government, either directly or via a contractor, but there isn’t a single job on that list that “must” be done by government. The fatality rate for all government occupations, incidentally, is 2.5 per 100,000.

Which means that in our society, as in every other, it is the private producers, rather than the parasitical tax-feeders, who face the greatest dangers on a daily basis.

If you work as a logger, farmer, field worker, truck driver, or in an occupation that requires a long daily commute, your job is statistically more dangerous than law enforcement.

According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, there were more than 1.1 million full-time police personnel on duty as of 2004. Rounding that figure down to 1 million, and accepting Taser International’s officer fatality figure of an average of 145 per year, would produce an average workplace fatality rate of about 14.5 per 100,000 employees for the police – well below the lethal attrition rate the BLS found for Agricultural Workers. While this comparison isn’t an exact match (the BLS figure encompasses all work-related deaths, not just those resulting from violent crime), it’s close enough to validate my point.

A new book entitled Some Gave All: A History of Baltimore Police Officers Killed in the Line of Duty, estimates that between 1792 and 2007, 17,900 federal, state and local law enforcement officers were killed. That works out to an average of a little more than 83 a year over 215 years. And it stands to reason that the annual death toll – assuming the figure is accurate — must have risen dramatically at some point in order to pull that average up (for one thing, there were no federal law enforcement officers prior to the early 20th Century).

This would suggest that, statistically, law enforcement has never been a particularly dangerous occupation, even during the frontier period. Make that “particularly” during the frontier period, when miners, railroad workers, homesteaders, and others probably faced sudden and often violent death much more often than law officers did.

(And don’t even get me started on the subject of the mortality rate for dispossessed Indians taken into the care of the federal government.)

By way of contrast, there is reason to believe that the danger of violent encounters between common citizens and police has grown appreciably in recent years.

A study publicized by Wired about a year ago suggested that an American’s odds of being killed by terrorists were slightly lower than his odds of being shot by a law enforcement officer. That comparison isn’t entirely sound, since even now the overwhelming majority of those killed by police are people suspected of committing crimes against persons or property, rather than commonplace citizens innocently trapped in bad circumstances.

For me, this is a key question: Is the number of unambiguously innocent citizens killed by the police greater than the number of police killed in the line of duty?

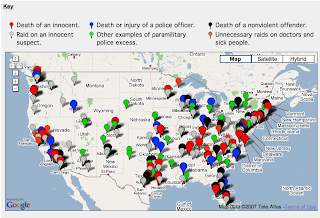

A very incomplete map of paramilitary police raids involving deaths or injuries (click to enlarge).

According to Joseph D. McNamara, a former police chief in Kansas City, Missouri and San Jose, California, police work is actually less dangerous today that it was in the late 1960s and 1970s. Writing in the Wall Street Journal about a year ago, McNamara observed that 51 officers were killed in the line of duty in 2006 “out of some 700,000 to 800,000 American cops [meaning sworn personnel with arrest powers]. That is far fewer than the police fatalities occurring when I patrolled New York’s highest crime precincts.”

If this is the case, why is police violence continuing to escalate?

“Simply put, the police culture in our country has changed,” McNamara explains. “An emphasis on `officer safety’ and paramilitary training pervades today’s policing, in contrast to the older culture, which held that cops didn’t shoot until they were about to shoot or be stabbed. Police in large cities formerly carried revolvers holding six .38-caliber rounds. Nowadays, police carry semi-automatic pistols with 16 high-caliber rounds, shotguns and military assault rifles, weapons once relegated to SWAT teams facing extraordinary circumstances. Concern about such firepower in densely populated areas hitting innocent citizens has given way to an attitude that police are fighting a war against drugs and crime and must be heavily armed.”

Arguably the single biggest source of unnecessary police violence is the “War on Drugs,” which has also nurtured police corruption and begotten countless abuses of the Bill of Rights. That “war” is actually a perverse symbiosis between the criminal underworld – which has a federally enforced monopoly on marketing substances once entirely legal in this country – and the law enforcement agencies that suck up huge federal subsidies in the name of “fighting” those same drug traffickers.

This cynical charade has abetted the militarization of law enforcement and the proliferation of no-knock raids, which result in needless death and life-threatening injury to both police and innocent civilians.

A typical monument memorializing police who died in the line of duty. Where are the monuments to innocent civilians who died needlessly from police violence?

These are some of the reasons why Chief McNamara, like many other current and former police officers of integrity and principle, joined Law Enforcement Against Prohibition (LEAP), which is agitating for an end to the War on Drugs, which is the single largest preventable cause of law enforcement violence against the innocent.

There are reasons – both constitutional and ethical – to believe that the law enforcement apparatus as it presently exists is fundamentally misbegotten.

Pending that welcome day when the public can force the political class to revise or abolish the institutional impediments to genuine individual liberty, the most useful reforms would be to end the Drug War, and to begin the comprehensive de-federalization of law enforcement at all levels.

This won’t happen, of course, until the public at large liberates itself from many State-imposed delusions, among them the idea that police work is somehow a sacred and uniquely dangerous occupation.

Update, November 28

Thanks to a comment from an alert and well-informed reader, I am now aware of Chief McNamara’s long and impassioned commitment to the cause of civilian disarmament. How one can be so clear-headed in opposing drug prohibition, yet so misguided on the even more fundamental question of the right of individuals to armed self-defense, is a question I’m not competent to answer.

This is particularly perplexing in light of the fact that McNamara clearly understands the growing danger posed by militarizing the police — yet he doesn’t understand how this process is related to the question of civilian disarmament. He clearly wants to de-militarize the police, but enforcing “gun control” laws leads to exactly the opposite result: If the State is going to compel this citizenry to surrender its firearms, it will ultimately have to resort to military or para-military means, by either militarizing the police or deploying the National Guard or other military assets domestically.

Vide what took place in post-Katrina New Orleans as a perfect example:

All hail our heroic local police at work!

Men of integrity and principle can be earnestly mistaken about some important matters; I think this best describes McNamara’s present situation. It is to be hoped that he will change his views on this supremely important question. Pending that welcome development, his insights regarding the dangers of police militarization are all the more valuable, coming as they do from someone who cannot be accused of harboring “anti-government” sentiments.

A Brief Personal Note:

I have just learned that my former colleague Gary Benoit, editor of The New American magazine, is seriously ill. For many years before this happened, Gary was a good and generous friend. Those of you who pray, please take a moment to offer a petition to God on behalf of Gary and his very large and delightful family.

Dum spiro, pugno!

Content retrieved from: http://freedominourtime.blogspot.com/2007/11/lets-be-careful-out-there.html.