Friday, June 27, 2008

The Heller Misdirection

Freedom! Glorious freedom!

A young American celebrates the freedom to pee under the kindly gaze of one of our nation’s many fine paramilitary police officers.“A nation of slaves is always prepared to applaud the clemency of their master, who, in the abuse of absolute power, does not proceed to the last extremes of injustice and oppression.” —

Edward Gibbon, Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire

Like the inhabitants of other formerly free societies, Americans are content to define “freedom” in terms of those liberties we are permitted to exercise. Yesterday’s Supreme Court ruling in District of Columbia v. Heller (.pdf) is perfectly in harmony with this self-defeating concept of “freedom.”

It is entirely appropriate that the decision was written by Antonin Scalia, the most reliably authoritarian and consistently liberty-averse member of the Court. With an air of regal condescension, Scalia allows that the Second Amendment acknowledges and protects an individual right to armed self-defense. He then explicitly limits the extent to which that “right” can be exercised, thereby redefining it as a State-conferred privilege.

We can’t really expect a statist creature like Antonin Scalia to embrace the view that the right to keep and bear arms includes the right of citizens, acting either individually or collectively, to kill agents of the state when such action is necessary and morally justified. Any other view of the Second Amendment is worse than useless; this is certainly true of the view that emerges in Scalia’s Heller opinion.

“The Second Amendment protects an individual right to possess a firearm unconnected with service in a militia, and to use that arm for traditionally lawful purposes, such as self-defense within the home,” summarizes Scalia at the beginning of his opinion (emphasis added).

A few paragraphs later Scalia elaborates a bit on the implied limitations of the “right” he describes. Insisting that previous Court rulings effectively limit “the type of weapon to which the right applies to those used by the militia, i.e., those in common use for lawful purposes,” he asserts: “Like most rights, the Second Amendment right is not unlimited. It is not a right to keep and carry any weapon whatsoever in any manner whatsoever and for whatever purpose…. Miller‘s holding that the sorts of weapons protected are those `in common use at the time’ finds support in the historical tradition of prohibiting the carrying of dangerous and unusual weapons.” (Emphasis added.)

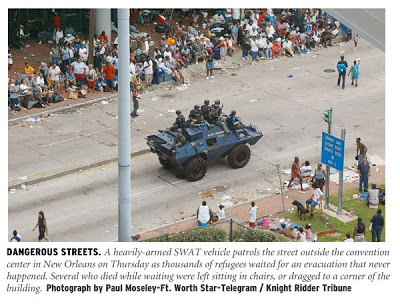

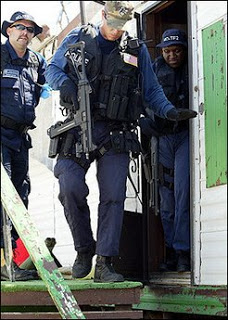

Nothing “dangerous and unusual” here: Combat-armed occupation troops patrol Katrina-ravaged New Orleans as part of an operation that included disarmament of law-abiding citizens.

When government grants a liberty and then restricts the manner in which it can be used, the result is not a right, but a limited, conditional license. Scalia’s passage cited above will inevitably be seen as a license from the court for legislative bodies to enact, or fortify, laws against “dangerous and unusual” weapons — such as the scary-looking guns ritually denounced as “assault weapons, for example. And other even more troubling portions of his opinion will abet further restrictions on the purposes for which firearms can be used.

At various points in his opinion, Scalia brushes up against the radical origins of the Second Amendment. For example: “The Antifederalists feared that the Federal Government would disarm the people in order to disable [the] citizens’ militia, enabling a politicized standing army or a select militia to rule. The response was to deny Congress power to abridge the ancient right of individuals to keep and bear arms, so that the ideal of a citizens’ militia would be preserved.” (Pg. 2; see also 22-28)

The clear implication here is that the “ancient right of individuals” to armed self-defense includes the right to organize for the purpose of insurrection against a tyrannical government. Scalia revisits that theme in reviewing efforts by George III’s government to disarm American colonists (pg. 21). Discussing the ancient origins of the right, Scalia notes that “the Stuart Kings Charles II and James II succeeded in using select militias loyal to them to suppress political dissidents, in part by disarming their opponents” (pg. 19). He quite usefully admits that “when able-bodied men of a nation are trained in arms and organized, they are better able to resist tyranny” (pp. 24-25), without teasing any specific application from that provocative observation.

Although he draws only scantily from the vast corpus of insurrectionary writings by the Founders that deal with the right to armed self-defense (the most notable being Madison’s endorsement, in Federalist essay 46, of direct military action against a tyrannical central government), Scalia does cite some interesting literature of that sort from the mid-19th century.

For instance, he quotes John Norton Pomeroy’s 1868 book An Introduction to the Constitutional Law of the United States, which stated that the Second Amendment would make no sense unless it enables citizens “to exercise themselves in the use of warlike weapons. To preserve this privilege, and to secure to the people the ability to oppose themselves in military force against the usurpations of government, as well as against enemies from without, that government is forbidden by any law or proceeding to invade or destroy the right to keep and bear arms….” (emphasis added).

From the foregoing it’s clear that Scalia is aware of the insurrectionary origins and purpose of the Second Amendment. Passages of that sort are scattered through the 67-page opinion and left without significant elaboration.

What’s even odder is the fact that Scalia, drawing on Joseph Story’s immensely influential Commentaries, asserts that the “free state” to be defended by the people under arms is not the individual state they inhabit — as the Founders would have understood — but rather the unitary nation created as a result of the Union victory in the War Between the States (pg. 24).

Scalia appears to be saying that while the right to bear arms was associated with the colonial and state militias, that right does not exist exclusively to carry out that function. But he also seems to assert that since the modern “militia” is an institution controlled by the central government and devoted to its protection, there’s no longer a legitimate right to armed self-defense against the government.

On this point, Scalia’s analysis is difficult to distinguish from that offered by the dissenting judges, who would simply dispense with the right to bear arms entirely, rather than paying lip-service to it while denying its chief purpose and encouraging various encumberances on it, as Scalia does.

“Undoubtedly some think that the Second Amendment is outmoded in a society where our standing army is the pride of our Nation, where well-trained police forces provide personal security, and where gun violence is a serious problem,” Scalia concludes. “That is perhaps debatable, but what is not debatable is that it is not the role of this Court to pronounce the Second Amendment extinct.”

Indeed not: Scalia’s opinion suggests that the role of the Court is to placate key elements of the Republican coalition while suggesting alternative routes to those who seek the eventual abolition of the right that was once protected by the Second Amendment. While Scalia’s ruling reinforces one of the few effective rallying points for the demoralized Republican Party (“This year’s election is all about the judges!”), it does nothing of substance to defer the day when some judge or president will be able to pronounce the Second Amendment extinct.

This point simply can’t be emphasized too often: The innate right of armed self-defense exists whether any government chooses to recognize it. What made the Second Amendment unique was its recognition of the fact that in the constitutional scheme, the government does not have a monopoly on the legitimate use of force. Scalia, like many statist jurists before him, insists that the permissible civilian uses of firearms are all defined within that government-exercised monopoly on force; they are temporary concessions that can be redefined by our rulers at whim.

In a genuinely free society, citizens would enjoy the unqualified liberty to acquire weapons of any sort, in any quantity they pleased, for the specific purpose of being able to out-gun the government and its agents when such action would be justified.

Your friendly neighborhood stormtrooper on patrol in New Orleans: If they were really the Good Guys, would they dress like this?

Most Americans, as ignorant of our heritage of principled insurrection as they are well-versed in the ephemera of degenerate pop culture, would find such sentiments abhorrent. In that fact we see that — whatever may be the status of our current “right” to keep and bear arms — the intellectual and psychological disarmament of our population is nearly complete.

Errata

Please note that the original version of this essay cited Federalist essay 45 rather than 46, although the link was correct. My thanks to LewRockwell.com reader Brian Martin for catching this error (and many thanks to Lew for republishing this essay on his irreplaceable website).

Also, in the original version of this essay I omitted the word “asserts” following mention of “… Joseph Story’s immensely influential Commentaries….”

Ah, the dangers of being one’s own copy editor, particularly when the author in question frequently finds himself writing with a youngster clinging to one arm….

Dum spiro, pugno!

Content retrieved from: http://freedominourtime.blogspot.com/2008/06/heller-misdirection.html.