“Your Papers, Please” — Simplified

(A quick note: There is a brief update on the Derek Hale case at the end of this essay.)

Deltha O’Neal, the Pro Bowl cornerback for the Cincinnati Bengals, was arrested at a DUI checkpoint last December. When O’Neal showed up at he municipal courthouse in Batavia, Ohio a few weeks later to attend a pre-trial hearing, he was asked for his Social Security number by a deputy sheriff; the information was entered into a hand-held Mobilisa m2500 Sentry scanner.

“The check mark that flashed onto the device’s 3.8-inch color screen indicated O’Neal had no outstanding local warrants, wasn’t among the FBI’s most wanted, and also wasn’t on Interpol’s terrorist watch list,” reported the Cincinnati Enquirer. “Data from more than 140 sources – including the US Drug Enforcement Agency and Customs Enforcement – were cross-checked by the device to determine whether deputies should detain the pro football player.”

O’Neal was permitted to pass through the metal detector and enter the courthouse without further complications. That wasn’t the case for many other courthouse visitors, dozens of whom were cited or taken into custody as a result of random ID checks.

The Sentry device is a black hand-held multi-function computer that looks a bit like an over-sized hand phaser from Star Trek.

It is equipped with a scanner that can read the magnetic strip or barcode that is a standard feature in state-issued licenses and ID cards, as well as passports and military IDs. The unit can be customized for license plate recognition or crime scene documentation as well.

Database updates are downloaded by the Sentry when it is docked with its charging bay, and the unit can send and receive data through a wireless network when used in the field. The device is – to use the grotesque military neologism — “ruggedized,” meaning that it can be used in the rain and won’t be broken if it is dropped.

The Sentry scanner is, quite literally, a garrison state technology. Originally developed as a security measure for military bases, the Sentry began law enforcement field tests last September when Mobilisa donated three units to the Clermont (Ohio) County Sheriff’s Department: Mobilisa chairman John W. Paxton, Sr., a former New Hampshire state trooper, lives in the county and is a personal friend of the sheriff.

Micheline Mendelsohn, Communications Director for Mobilisa, explained to me that the while the Sentry system is being used at 23 military bases (including Andrews Air Force Base), the Clermont County Sheriff’s Department is the only civilian law enforcement agency to use the scanners so far. But this is likely to change soon.

“The Ohio example really excited people and started a snowball effect,” Mendelsohn told me. “And this really began with the military trials. Somebody looked at the device and said, `Hey – this would be great for law enforcement,’ so we went in that direction. And it really is ideally suited for police when they’re conducting traffic stops, for example, since the officer doesn’t have to turn his back when he’s trying to access the information.”

Mobilisa is working to make the Sentry even more user-friendly, according to Mendelsohn: “We have in development an even smaller hand-held device that would be about the size of a cell phone, and could be clipped to a belt.”

According to promotional literature from the company, in 2003 Mobilisa “requested funding for a project to secure our nation’s military bases….” When asked about additional federal funding to develop and distribute the Sentry system, Mendelssohn replied, “We’re just starting on that road. We’ve gotten great response from the military, which was the original intention behind developing the technology.”

She did agree that local police departments would find the Sentry technology a very attractive choice when looking to spend federal homeland security grants. (It’s interesting that the first use of the Sentry system came during a federally subsidized DUI checkpoint in Ohio last fall.) As with other technologies, we can expect to see the Sentry become commonplace very quickly, and for police departments to resort to its use quite promiscuously.

From the perspective of those concerned with civil liberties, the real mischief inherent in this system is not found in the technology itself, but rather in the data streams it can channel to police officers considering whether or not to “detain” an individual.

There are 29 entries on Mobilisa’s list of “Persons-Of-Interest Databases,” many of them drawn (predictably, given Sentry’s origins) from various military investigative agencies. The FBI, ATF, DEA, ICE, and other alphabet agencies are well-represented, as are the State Department, Secret Service, National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, two state Corrections Departments, and the Postal Service. The information available through Sentry, boasts the company, is “virtually limitless.”

The twenty-ninth data source is the provocative catch-all category, “Various Other Local Law Enforcement Inputs.” This would include information on criminal records and driving histories, as well as other unspecified details fed into various databases by police agencies. Information of this kind has a very long half-life, and can make an individual radioactive where freedom of movement is concerned.

San Francisco Chronicle columnist C.W. Nevius recounts the experiences of several US citizens who found it difficult or impossible to visit Canada because of ancient misdeeds unearthed by the new Smart Border Action Plan, which “combines Canadian intelligence with extensive US Homeland Security information. The partnership began in 2002, but it wasn’t until recently that the system was refined.”

Canadian customs officials “can call up anything that your state trooper in Iowa can,” observes Canadian attorney David Lesperance.

This is why some Americans wanting to travel to Canada on business or for recreation have been turned away, or forced to undergo lengthy and detailed additional scrutiny, because of long-forgotten drug or drunk driving convictions, or other misdemeanors. One of Lesperance’s clients was turned away at the border for a 20-year-old shoplifting conviction that resulted from a fraternity prank. Another case involves an American deemed inadmissible to Canada because he was convicted of possessing marijuana more than thirty years ago.

Lesperance points out that the data-sharing agreement between Washington and Ottawa “is just the edge of the wedge,” since similar agreements are being negotiated with countries across Europe and Asia that are familiar destinations to business travelers.

Through the dubious miracle of the Sentry scanner, state troopers in Iowa and security police abroad will enjoy instant access to a data pool containing ancient transgressions of the sort described above, thereby creating all kinds of potential pretexts for harassing and detaining decent and otherwise law-abiding US citizens.

After describing the case of a friend who was denied access to Canada after the new system went into effect last January, libertarian commentator Wendy McElroy points out that data-sharing protocols of this sort mean that some “travelers may well be denied entry [to their chosen destinations] on a global level because of a youthful indiscretion or an arrest for unlawful assembly (e.g. an anti-war rally).”

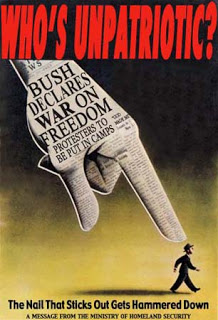

Taking names? A police cruiser from Department of Homeland Security kept watch at a recent anti-war demonstration outside Speaker Pelosi’s office in San Francisco. (Courtesy AntiWar.com)

McElroy’s chosen example is a particularly timely one, given the recent experience of Walter F. Murphy, a retired Marine Colonel (who was decorated for valor during the Korean War) and professor emeritus of Princeton University.

As recounted in a letter posted on Mark Graber’s blog, Balkinization, when Murphy attempted to check in for a March 1 American Airlines flight to Newark, he discovered that his name had been placed on a “terrorist watch list.”

“I presented my credentials from the Marine Corps to a very polite clerk for American Airlines,” recalled Professor Murphy. “One of the two people to whom I talked asked a question and offered a frightening comment: `Have you been in any peace marches? We ban a lot of people from flying because of that.’ I explained that I had not so marched but had, in September, 2006, given a lecture at Princeton, televised and put on the Web, highly critical of George Bush for his many violations of the Constitution. `That’ll do it,’ the man said.”

Consider, briefly, what this incident says about the reasons for which a person can be detained (as Murphy was, briefly, for additional security screening) – and, therefore, the potential applications of the Sentry scanning technology:

Murphy wasn’t prevented from boarding because of a crime he had committed, even a long-buried youthful indiscretion. His presence on a “watch list” didn’t come about because he had been arrested for “unlawful assembly,” or even for peaceful participation in a legal protest march. His name was enrolled on that infamous list because of a speech he had given criticizing the Dear Leader.

It’s likely that the identities of peace protesters – who are, remember, frequently banned fliers, according to the official with whom Murphy spoke – were almost certainly compiled by local police, including undercover operatives. Who took down Murphy’s name and fed it into the database? Some low-level Republican Party functionary who read a news account of the speech, perhaps? Could it have been an overzealous campus security drone, or an offended audience member who called a hot line? We’ll never know.

What we do know is that Mobilisa’s uber-slick new gadget will certainly simplify things for State agents (whether here or, eventually, abroad) who trying to “find a reason” to lock up troublesome citizens – and complicate life tremendously for those of us on the receiving end of this system of human inventory control.

Derek Hale Update

The attorneys who have filed suit on behalf of Derek Hale’s widow, orphaned stepchildren, and parents are working pro bono. However, there are many other expenses involved in a civil suit, particularly one filed against intransigent government agencies that can fob those costs off on local taxpayers.

Accordingly, a legal defense fund has been established on behalf of Derek Hale’s survivors:

The Derek Hale Defense Fund

c/o Dr. David Crowe

1736 Broadway

Cape Girardeau, MO 63701

Stephen J. Neuberger, a Wilmington, Delaware civil rights attorney involved in the lawsuit, explained to me that Dr. Crowe “has known Derek since he was a little kid,” and wants to do what he can to help his family see that justice is done. Neuberger also promised me that “Any donations to the fund will go to pay out-of-pocket costs, and not attorneys’ fees.”

Please visit The Right Source for the latest news from the freedom battlefront.

Content retrieved from: http://freedominourtime.blogspot.com/2007/04/your-papers-please-simplified.html.