Two hundred years ago, Benjamin Constant foresaw the rise of humanitarian intervention as the foremost modern pretext for war. In the age of commerce and democracy, the state had to concoct “scandalous lies” to subvert the peaceful international order based on free trade, he argued.

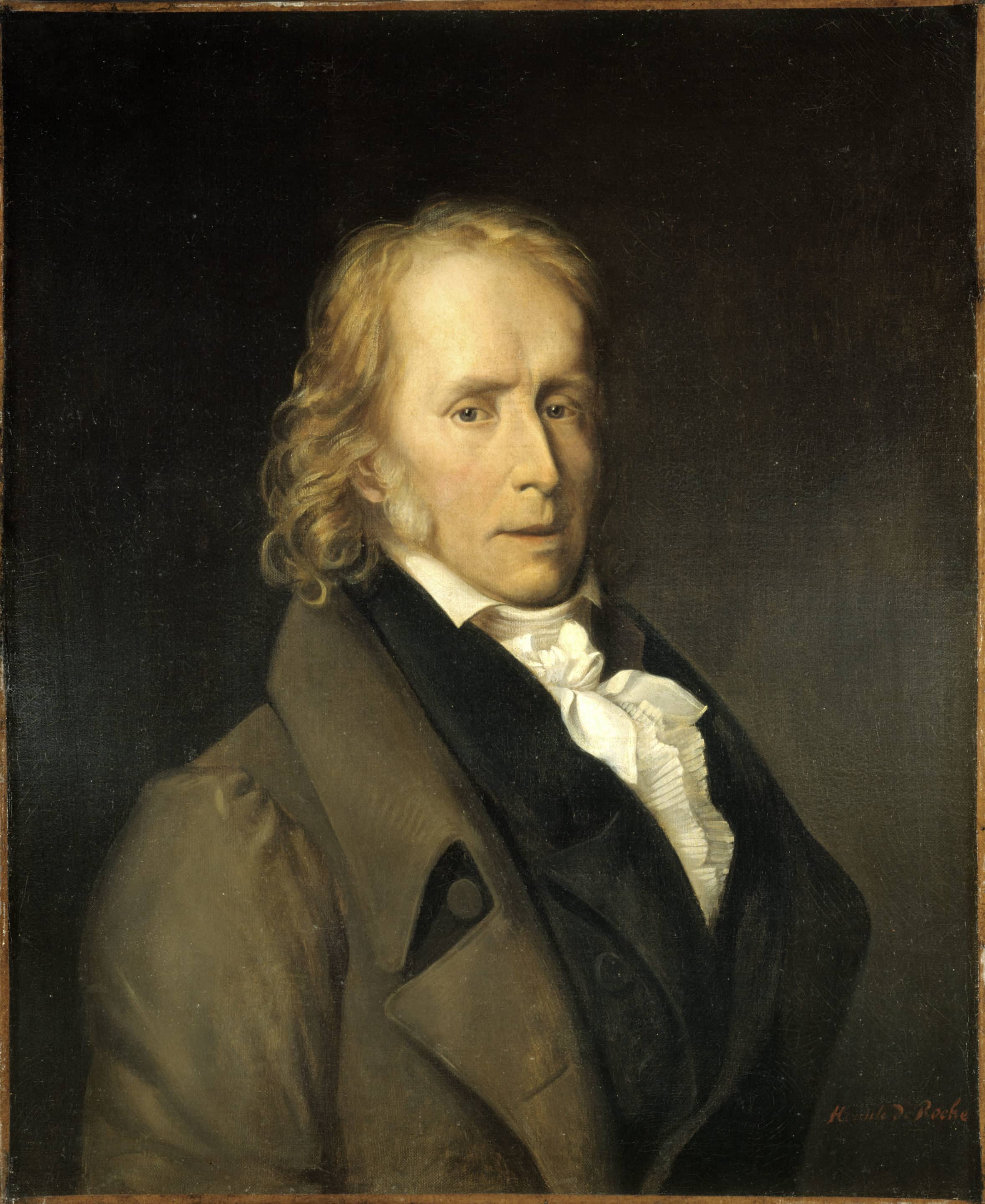

In 1814, as Napoleon Bonaparte was shipped to Elba after the Battle of Leipzig had put a (temporary) stop to the general’s short-lived empire, the French classical liberal Benjamin Constant published a short book entitled De l’esprit de conquête (‘On the Spirit of Conquest’). Constant had previously supported Napoleon, but this devastating critique of foreign adventurism demonstrated his disillusionment with the wars that had ravaged Europe ever since the French Revolution.

What’s more, Constant made a number of prescient observations about foreign policy that ring as true today as they did at the eclipse of Napoleon’s rule.

In 1776, Adam Smith had already exposed the association between mercantilism and war in The Wealth of Nations. Conversely, Constant, foreshadowing the mid-nineteenth century teachings of the British free trade activist Richard Cobden, demonstrated that free trade and peace are two sides of the same coin. He argued that war had become redundant in the modern age because voluntary trade had come to dominate international relations at the expense of coercive inter-state affairs:

We have arrived at the age of commerce, which necessarily replaces the age of war, just like the age of war necessarily had to precede the age of commerce. War and commerce are nothing but two different means at achieving the same goal of possessing what we want to possess…War is thus anterior to commerce. The one is the savage impulse, the other the civilised calculus…A government that would push war and conquests on a European people therefore commits a gross and terrible anachronism. It labours to give to that nation an impulse contrary to nature.

As an economist would put it, there are basically two ways by which we can try to satisfy our desire for goods and services; through the market or through robbery and enslavement—or, on international scales, by peaceful exchange or by violent conquest. According to Constant, the breakthrough of international trade, bolstered by the writings of the classical liberals, had revealed the superiority of the former means.

Still, the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars served as a painfully reminder that war had not yet disappeared from the face of the earth. Contrary to later intellectuals like John Stuart Mill, John Hobson, and Vladimir Lenin however, Constant did not point the finger at capitalism as the culprit. Quite the contrary, in fact. He laid the blame for the continued eruption of war squarely at the feet of the state.

“Nowadays,” he reiterated, “war does not procure any advantage to the people and it can only be a source of privation and suffering for them.” This means that the government simply cannot be truthful in justifying foreign military engagement to the public. Yet, in the age of gradual democratic expansion, the population somehow had to be brought on board. The only solution, then, was for the government to come up with all sorts of “scandalous lies.”

From time immemorial, such pretexts of war had included prestige, national honor, and commercial interests. The latter excuse had already been debunked by Smith and other political economists. Prestige and honor, on the other hand, did not seem to be in tune with the times in the nineteenth century. The French Revolution, then, had given birth to a new pretext for war, the pretext of freeing foreign peoples “from the yoke of governments that we allege to be illegitimate and tyrannical.”

This statement proved to be prophetic. In 1859, as the Cobdenist policy of non-intervention was reaching its height of success in Britain, John Stuart Mill published an essay by the name of A Few Words on Non-Intervention. In it, he begrudgingly commented that Britain’s declared foreign policy doctrine was “to let other nations alone.” He, on the other hand, made a moral case for intervening in another nation’s affairs, on condition that the intention was to help freedom-minded people to resist foreign oppression.

Rather ironically, Mill dubbed this doctrine “intervention to enforce non-intervention.” Sooner than he could have imagined, this inconsistent doctrine became the essential basis of Western foreign policy. If we want to intervene in a certain country for whatever reason, we claim to fight for liberty. Think of the Boer Wars, the Spanish-American War, World War I, World War II, Korea, Vietnam, Iraq, the Balkans, Afghanistan, Iraq again, Libya, Syria, etc. Oftentimes, the stated intention is to get rid of oppressive dictators, even though we turn our heads at other, more cooperative tyrants. In the beginning of his administration, for instance, Joe Biden declared a global battle of democracy against authoritarianism in an apparent attempt to justify the United States’ new cold war against Russia and China. The American alliance with such oppressive regimes as Saudi Arabia and Egypt, meanwhile, continues to be swept under the rug.

Constant’s essay did not only predict the age of humanitarian war-mongering but also warned against the authoritarian backlash that war could have on the domestic front. The “scandalous lies” that serve as pretexts for war are not without consequences. The marketplace, at least in the long term, promotes honesty at the expense of dishonesty. On the other hand, as lying was a necessity for justifying foreign intervention in Constant’s view, he maintained that the opposite trend takes hold in a nation at war. There, the power of military men is strengthened, causing them to become increasingly contemptuous and intolerant of the liberties of civilian life. “Unanimity seems to them to be as necessary to public opinion as it is to the uniform of the troops,” Constant eloquently concluded. In contrast, “opposition is disorder, and reason a revolt.”

Here, too, Constant foresaw the future. The interconnection between foreign war and domestic authoritarianism was of course not new. Indeed, the dictatorship of Napoleon served as a vivid contemporary example. Looking at the United States of the twentieth century, Robert Higgs showed in Crisis and Leviathan that periods of crises, which are often defined by war, precipitate permanent enlargements of the government. And as a multitude of examples from history inform us, in wartime “Big Government” silences and persecutes dissent and enforces conformity.

Like the size of the government itself, moreover, the state is unlikely to roll back its wartime authoritarian reflexes after the conflict has reached an end. Indeed, one wonders if the lockdown policies of the last few years would have been tolerated by the public without the digital censorship practices that were developed during the Global War on Terror era and perfectioned after 2016 in the midst of hysterical fears about alleged Russian cyberwarfare against the West.

In the two centuries since Constant’s warnings, we have witnessed the state grow into the enormous monstrosity it is today for all the reasons he explained.