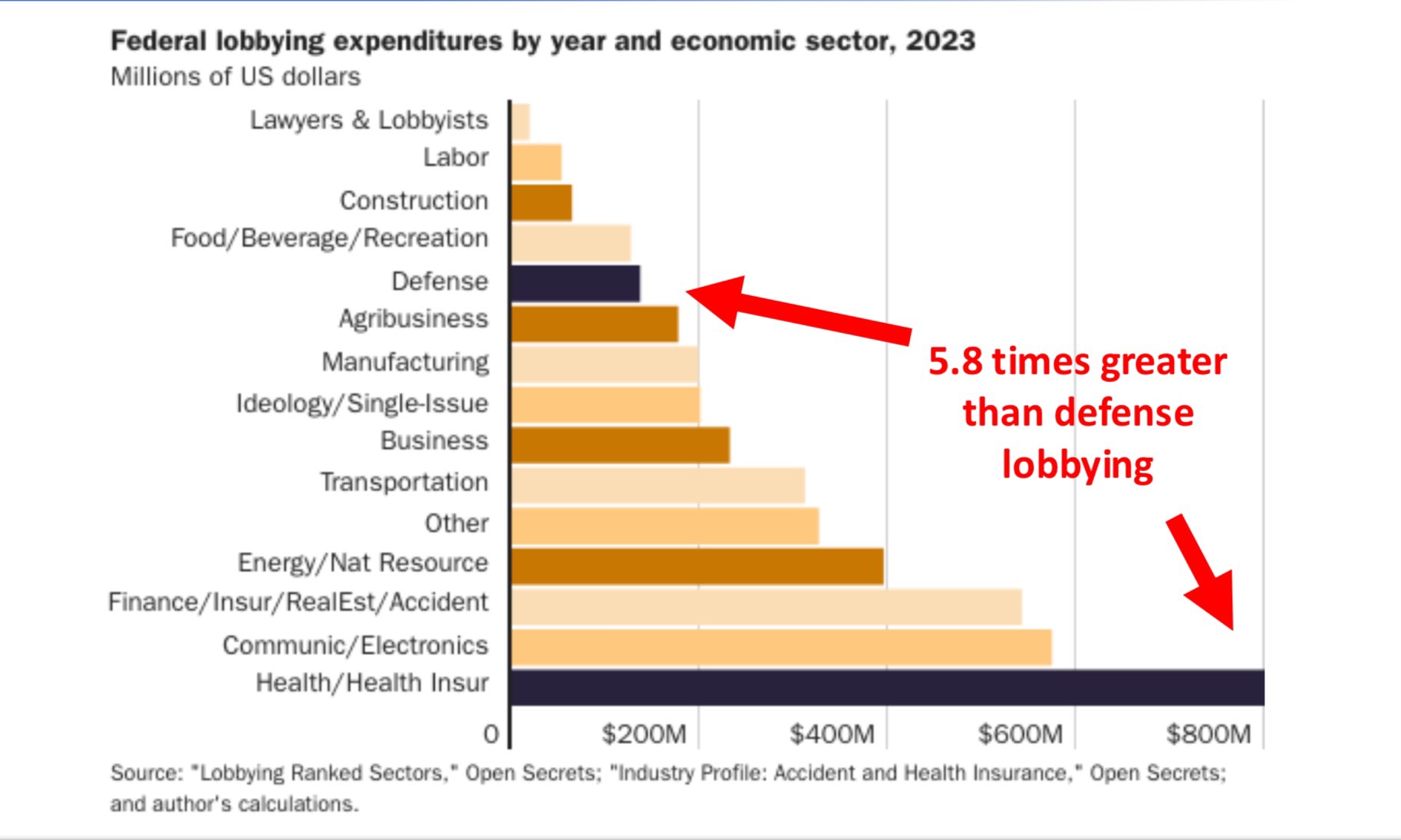

Contrary to a popular article of faith, America has no free market in health care—far from it. Consider this: the largest lobby in Washington, D.C., is—wait for it—the health care and health insurance industries. Last year, they spent 5.8 times the amount the “defense” contractors spent on lobbying: $800 million versus less than $200 million.

This may have many explanations, but the fact remains: a free market in health care would not see massive lobbying. Based on what Congress and regulatory agencies do, we can be sure that the health care and insurance industries are not by and large lobbying for less government. If so, they are doing a rotten job.

Michael F. Cannon, the Cato Institute’s director of health policy studies, wrote a book last year showing just how much of a free market in health America does not have. To call our system a free market is a bad joke, not to mention cruelly dishonest. The details—in addition to the lobbying data—are eye-opening. It’s like calling Sweden a socialist country. Wrong again, Bernie Sanders.

Cannon writes (PDF here):

In the United States … countless state and federal laws block innovations that would improve health care access and quality. Without exception, lawmakers enact these laws in the hope of reducing costs and improving quality. Without exception, they do extraordinary and irreversible harm to patients.

This book explains how state governments prevent medical professionals and entrepreneurs from offering higher-quality, lower-cost care. It explains how Congress denies consumers both control of trillions of dollars of their own earnings and the right to make their own medical decisions. It explains how Congress makes health care increasingly less affordable, jeopardizes patient health by promoting low-quality care, and makes health insurance work against the sick.

Cannon’s work is more than a diagnosis of the sickly U.S. health care system. It’s a regimen for moving America toward a “healthy” free market. The sooner we get started the better. For ages health care has been strangled by politicians, bureaucrats, regulators, and private-sector rent-seekers. They all need to be sent packing. We badly need entrepreneurship; free, flexible, private enterprise; and the profit motive—yes, the profit motive, the despised thing that has bestowed incredible wealth on so many people worldwide.

“In corners of the U.S. health sector where market forces have had room to breathe,” Cannon writes, the American system has achieved astounding innovations in diagnostics, service delivery, drugs, treatments, devices, and even insurance. But it fails on many counts thanks to government preemption of private market-based efforts. A good part of the reason Americans pay more for health care than anyone else in the world is government intervention. No surprise there if you understand how governments and markets work.

Cannon writes:

Among advanced nations, the United States ranks near the top in terms of government control of health spending. The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) collects data on 38 economically advanced nations. The OECD reports that in the average member country, 76 percent of health spending is compulsory. That is, rather than allow consumer preferences to allocate those funds, government requires residents to allocate those funds according to the government’s preferences or face penalties. In the United States, government controls a significantly larger share of health spending than the OECD average: 85 percent of U.S. health spending is compulsory.

The OECD country with the highest percentage of compulsory spending, the Czech Republic, beats the United States by only three points.

Government controls a larger share of health spending in the United States than in 30 other advanced nations, including Canada (75 percent) and the United Kingdom (83 percent), which have explicitly socialized health systems.

Some free market! Government dictates how 85 cents of every health care dollar is spent.

“Control over health spending and government-imposed barriers to accessing medication,” he goes on, “are just two ways government blocks the market forces of individual choice, innovation, and competition that would otherwise make health care better, more affordable, and more secure.”

Not all action is at the national level, of course. State governments heavily regulate health care and insurance. All these regulations, including licensing and the tax exclusion for employer-sponsored medical insurance, must go if Americans are to have a world-class free market in health care. Patients must be placed at the center so they can exercise what Ludwig von Mises called “consumer sovereignty.”

“Day after day,” Cannon concludes, “U.S. patients suffer the consequences of a century of mounting government failures. American health care is worse, more dangerous, more expensive, and less secure than what a market system would deliver.” People have to rethink their moral and aesthetic biases against profit-motivated, mutually beneficial market relations. It really is a matter of life and death.