What accounts for the preoccupation with income and wealth inequality? We hear about it every day. Isn’t our absolute living standard what matters and whether it is improving or deteriorating? I’ll bet that’s what regular people care about. However, the professional grievance mongers see things differently, They want you to resent those who are richer.

To start with the basics, we are not talking about inequality. We’re talking about income and wealth differences. Substitution of the term inequality is an appeal to emotion, a cashing in on other senses of the word. “You oppose equality? Don’t you believe that ‘all men are created equal’?” That’s demagoguery not argument.

In a market-oriented economy, most income is not distributed. There’s no distribution to describe as equal or unequal, fair or unfair. (What the government does is another story.) As Ludwig von Mises, wrote 102 years ago in Socialism: An Economic and Sociological Analysis, “Under Capitalism incomes emerge as a result of market transactions which are indissolubly linked up with production.” That’s not distribution or allocation.

Mises continued:

We do not first produce things and afterwards distribute them. When products are supplied for use and consumption, incomes for the greater part have already been determined, since they arise during the process of production and are indeed derived from it. Workers, landowners, and capitalists and a large number of the entrepreneurs contributing to production have already received their share before the product is ready for consumption.

“[T]he concept of distribution is only figurative,” Mises added. What people call “the income distribution” is not the outcome of a grand allocation plan. It’s a snapshot of a dynamic, decentralized series of exchanges and is always subject to change.

People transact, trade, only when they expect to gain. Otherwise, they wouldn’t bother. That’s true for both parties to a transaction. It’s win-win. Among the things people trade are labor services for money and vice versa. That people have to work so they can eat is not the fault of employers, who also have bosses to satisfy; they’re called consumers. That’s the nature of reality. But in a free and competitive market economy, few people are dependent on only one buyer or one seller. They are free to choose.

If no distribution occurs in a market economy, then no redistribution is possible. When the government taxes our incomes and gives the money to others—be they low-income people or military contractors—that’s plain old distribution. And it’s illegitimate.

Taxation and other forms of political manipulation are objectionable even if large-scale wealth and income differences do not result. So that cannot be the primary objection. Political manipulation is objectionable because it aggresses against nonaggressors and disrupts the process that best serves consumers. It would be odd to say, “I see inequality, so I wonder what government manipulation has brought that about.” It would be reasonable to say instead, “I see government manipulation, so I wonder if, on top of all the other bad consequences, it also has disrupted the wealth-creation process.”

Economic differences among individuals and groups are to be expected among free people and ought not to arouse suspicions of illegitimacy. To expect economic equality as the default is to commit the fallacy Thomas Sowell has exposed concerning all sorts of disparities among groups. Uniformity is found nowhere in the world.

Everyone knows that people’s contributions to productive activities vary widely, with a relatively few people at the top and bottom and most in the middle. No mystery here. Individuals differ in intelligence, age, ability, disposition, upbringing, energy, alertness, patience, ambition, education, work habits, culture, risk tolerance, entrepreneurship, and much more. No one should be surprised that their contributions to wealth creation also differ vastly or that they change over time. Thus vast differences in income and wealth are to be expected. I couldn’t have done what Bill Gates, Steve Jobs, Serge Brin, or Jeff Bezos, did—and, appropriately, my income reflects that.

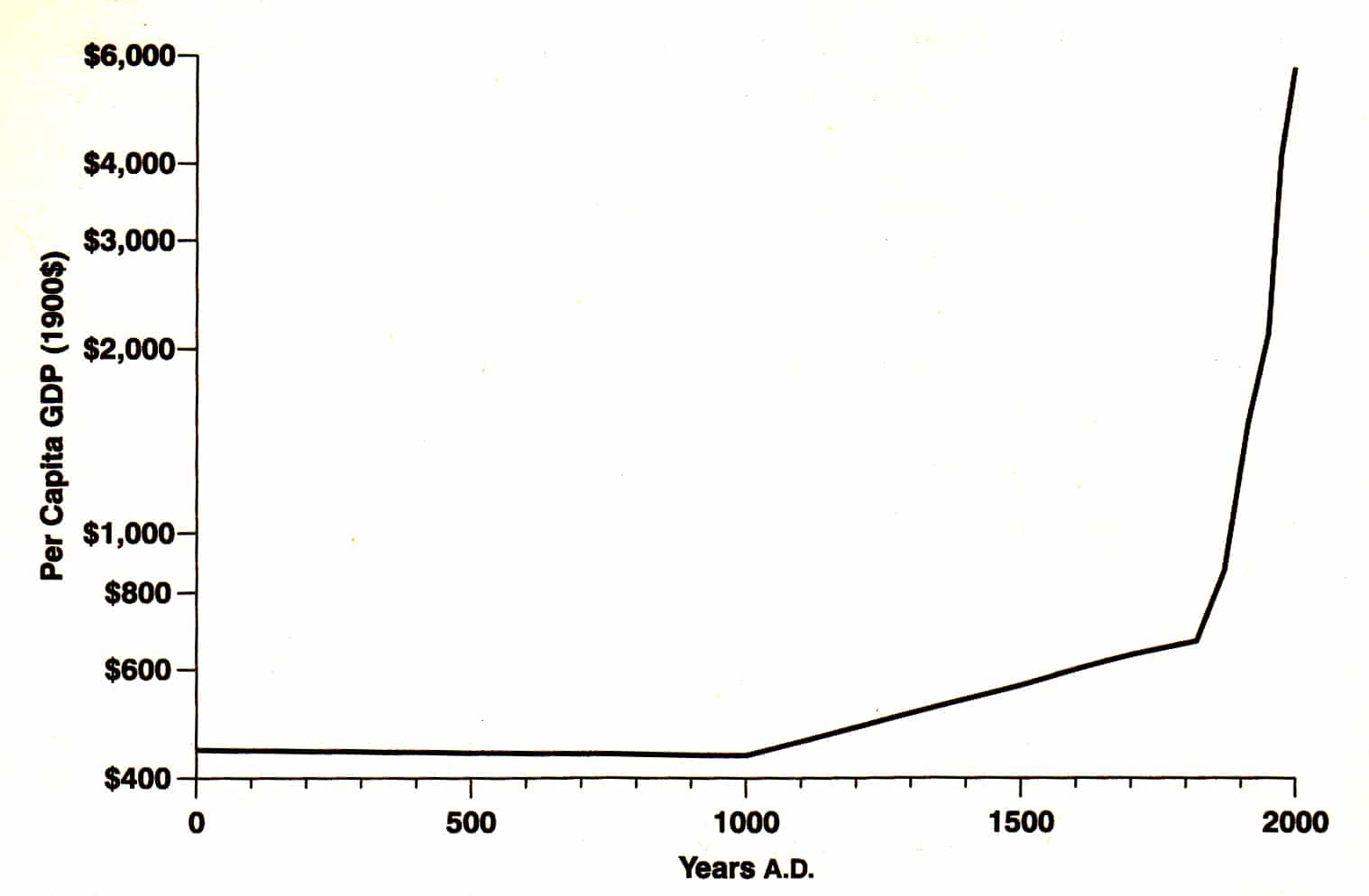

Despite the seeming paradox, the huge economic differences that can result from innovation benefit everyone. Much would be lost without that possibility. Incentives matter. Moreover, the innovators’ gains are minuscule compared to the total gains to consumers. A system designed to prevent or stamp out those rewards to innovation would impoverish us all. It would also put us on what F. A. Hayek called “the road to serfdom.”

It should also be noted that the price system, of which income levels are a part, signals to producers what consumers want most. It’s our way of telling producers where to put their efforts and scarce resources.

What indicates progress or regress in society is not the latest dubious measure of a gap between rich and nonrich, but how easily people of determination can climb the income ladder. If the government stays out of the way, the obstacles are minimized. Gaps don’t matter. Think of an elevator that can expand like an accordion: the floor can rise even if the distance to the ceiling increases.

Most people don’t envy wealthy innovators. They admire them. But anti-freedom politicians, intellectuals, and activists think you should resent anyone who is considerably wealthier. They’re running a scam designed to obtain power. We need to call them out.

If you like gaps, check out the shrinking consumption gap, the product of the growing availability of resources worldwide thanks to the spread of economic liberalization and the liberation of human ingenuity and entrepreneurship.