In the 2006 Mike Judge movie Idiocracy, the dumbed-down human population five-hundred years into the future have replaced water in drinking fountains with the salty sports drink “Brawndo,” and have even begun to water farm crops with Brawndo. Facing a nationwide famine as a result of repeatedly salting the crop fields, time-traveling twenty-first century slacker Joe Bauers suggests that the future-world dimwits use water for the crops rather than Brawndo. “But Brawndo’s got what plants crave,” the dimwitted White House advisors reply, echoing the official corporate marketing line repeatedly, “It’s got electrolytes.”

The movie is a warning about the dangers of blindly accepting the official propaganda line, not thinking critically, and not doing any of your own research. And I can’t help but see this movie scene every time someone tells me that lower interest rates stimulate the economy. “But lower interest rates have got what the economy craves,” they say. “It’s got stimulus.”

But does it?

Since the United States first engaged in its ultra-low interest rate experiment in the year 2000, the U.S. has only once in those twenty-four years attained a 3% real per capita GDP growth rate (the COVID snap-back year of 2021), while real per capita GDP growth sailed past 3% three times (or more) in each and every decade prior to 2000. Japan began its experiment with low interest rates in the early 1990s and it has been among the slowest growing economies in the world since then, growing at an average of less than one percent on a real per capita basis. And during the Great Recession, the only advanced economy to survive without a calendar year of negative economic growth was Australia, which had the highest interest rates of any advanced economy through the 2008-2009 recession years.

Joe Bauers said, “The plants aren’t growing, so I’m pretty sure that the Brawndo’s not working.” And I want to say, the economy is not being stimulated, and I’m pretty sure low interest rates are not working.

I’ve been on this kick since 2013 about low interest rates not accelerating economic growth. And I was happy to see I was not fully alone when my Libertarian Institute colleague Joseph Solis-Mullen published “The Federal Reserve, Interest Rate Suppression, and the Reach for Yield” on October 2. Solis-Mullen claimed of low interest rate skeptics that “the empirical record continues to bear them out. Artificially low rates do not create wealth; they reallocate risk and misallocate capital.”

Surprisingly, there is very little direct analysis of interest rates and economic growth among scholarly journals using real-world data. Google Scholar links to a few studies, which basically say “It therefore seems impossible to elucidate explicitly causal-effect relationships between interest rates and economic growth” or “there is only a weak relationship between real interest rates and economic growth.” Nobel Prize-winning economist James Tobin’s monetary growth model research was all theoretical on this topic. Likewise with the one popular economist duo who claimed low interest rates hurt economic growth: the McKinnon-Shaw hypothesis labeled artificially low interest rates a “financial repression,” but didn’t prove it out with data.

Who’s right: me, Solis-Mullen, a few Austrian economists, and McKinnon-Shaw, or most of the rest of the world’s economists? I decided to find out and see if I could tease out of the data stronger GDP numbers from countries with low interest rates.

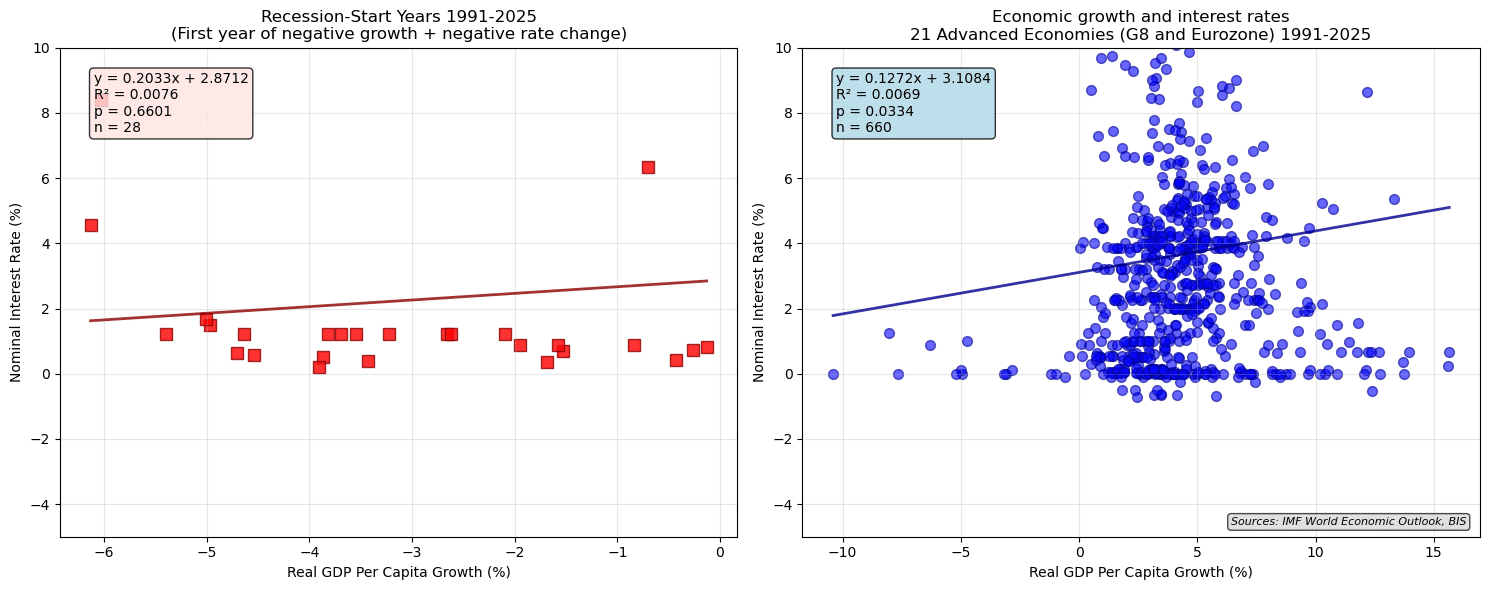

I went to the Bank of International Settlements database and pulled all the central bank interest rate records they had for advanced economies in the G8 and the Eurozone since 1990 and matched them up with real GDP numbers from the IMF WEO database for those countries (using GDP per capita purchasing power parity 2021 international dollars). And for Euro countries, I used the European Central Bank numbers after they joined the ECB. And just so that I didn’t mix my cause and effect—because I know central banks tend to lower interest rates in a recession—I had my Python computer program pull out those countries descending into negative GDP during years the central bank lowered interest rates and put them into a second chart.

The result of the computer regression were the graphs below, which found that higher interest rates generally were correlated with faster economic growth. The finding was statistically significant beyond the 96% confidence level (see the P-value), though it explained less than one percent of the GDP variance (see R2 statistic). The computer printed out the same trendline of low interest/low growth and high interest/high growth, but it could not determine if interest rates made a statistically significant (more than 95% confidence level) impact on GDP growth either way:

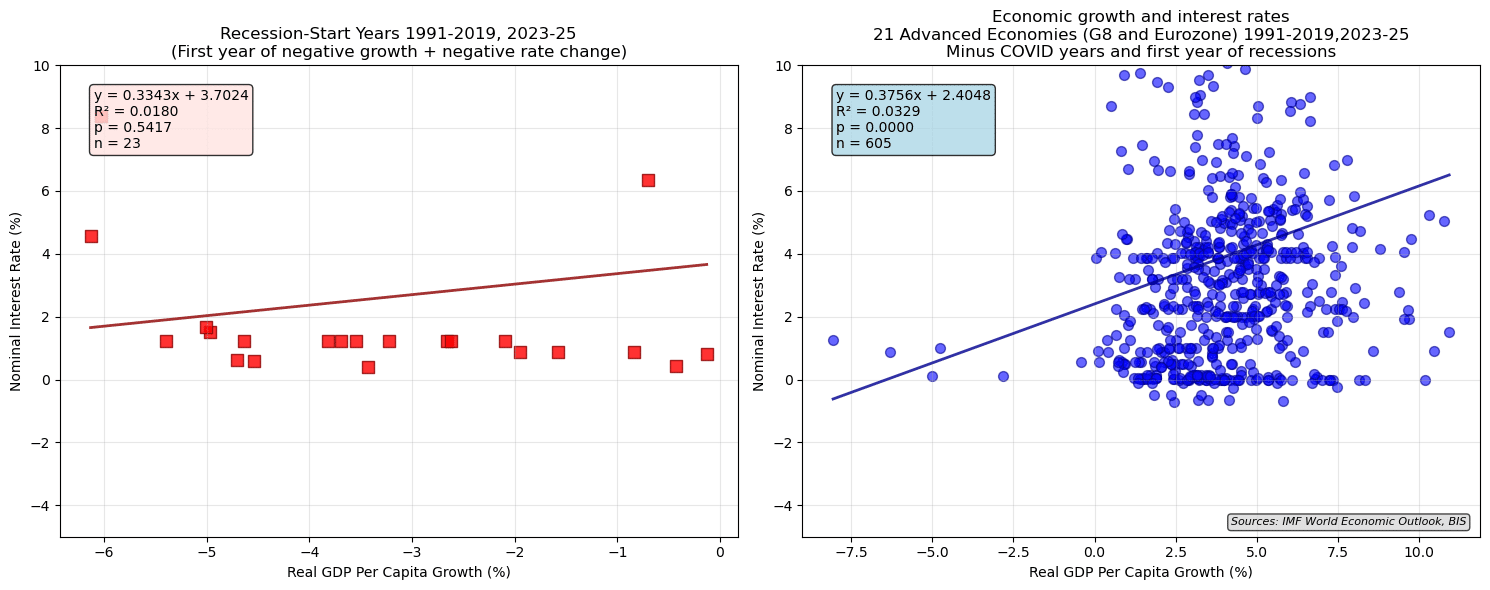

“But wait,” you might say, “maybe those COVID years are messing up the data. The recession in 2020 didn’t have anything to do with the underlying economy; it was just the government shutting everything down and printing a lot of money to create more inflation.” And if you said that, you’d be right. So let’s see what taking out the COVID and COVID snap-back years of 2020-22 does to the data:

The result of removing the COVID data is that the computer is even more sure that low interest rates have a negative impact on GDP growth during normal times, rather than the other way around. The computer indicates a statistically significant correlation to the 99.9% confidence level, and believes it explains a bit more than 3% of the data variance (compared to less than one percent with the COVID data). But in recession years where interest rates are falling, the computer again sees nothing statistically significant (despite the same slope of the regression line).

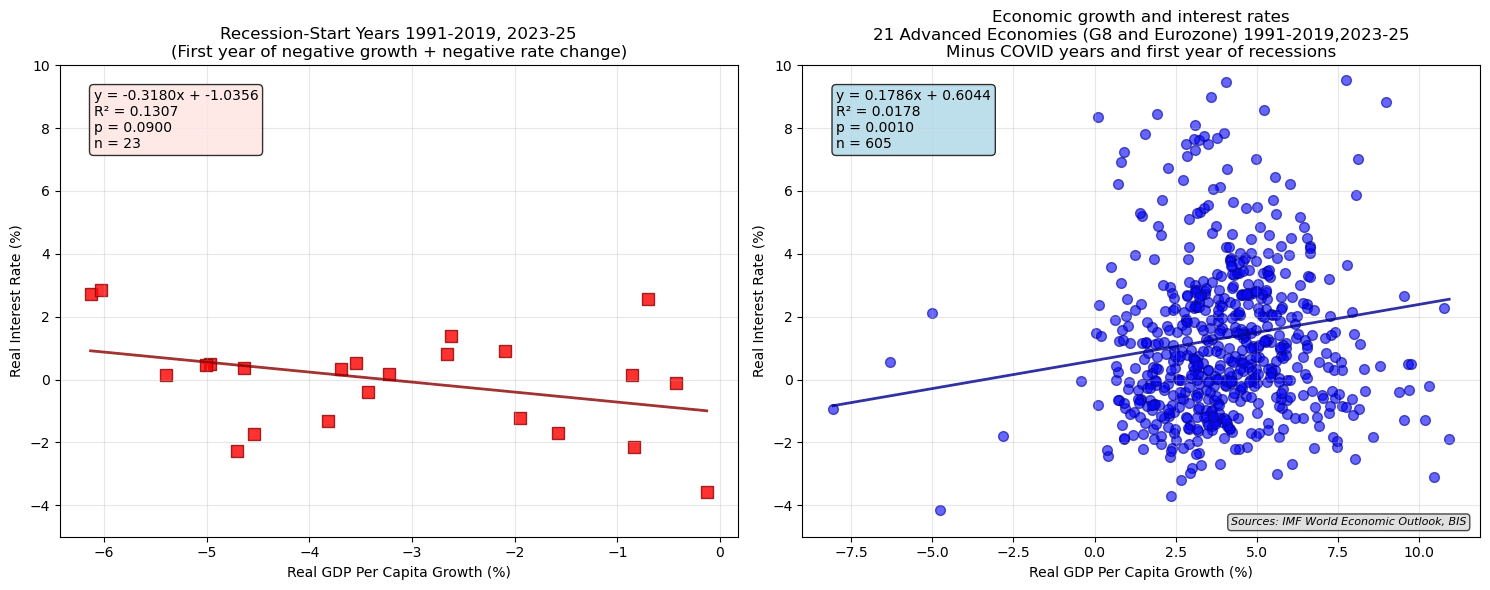

At this point, you might reply, “You haven’t falsified the assertion that low interest rates are associated with faster economic growth yet, because all you’ve done is look at nominal interest rates, the rates central banks announced, and not the real interest rate. The real interest rate is the nominal rate minus the inflation rate, which is the real price of money.” And again, your skepticism would be correct. So I took IMF WEO inflation numbers and subtracted them from the nominal rates provided by the BIS and ran the same Python regression, coming up with this:

Here, with real interest rates, the general trend is a bit weaker. But it still falsifies the assertion that low interest rates during normal times generates stronger economic growth to the confidence level of 99.9%. In the case of recession years where central banks cut the interest, the computer tells us that hasn’t quite reached the 95% confidence level that lower real interest rates moderate the harm in a recession. So in the latter case, it’s not disproven, there’s just no strong evidence in the statistics for the claim.

“Okay,” you may respond, “it’s not reasonable for the stimulus of lower interest rates to be recorded in the economic data in the year in which interest rates are lowered. It takes time for businesses to borrow money with the cheaper credit, hire people and produce more products. The real economic benefit of lower interest rates is in the year after rates are cut.” And this, too, is not an unreasonable objection.

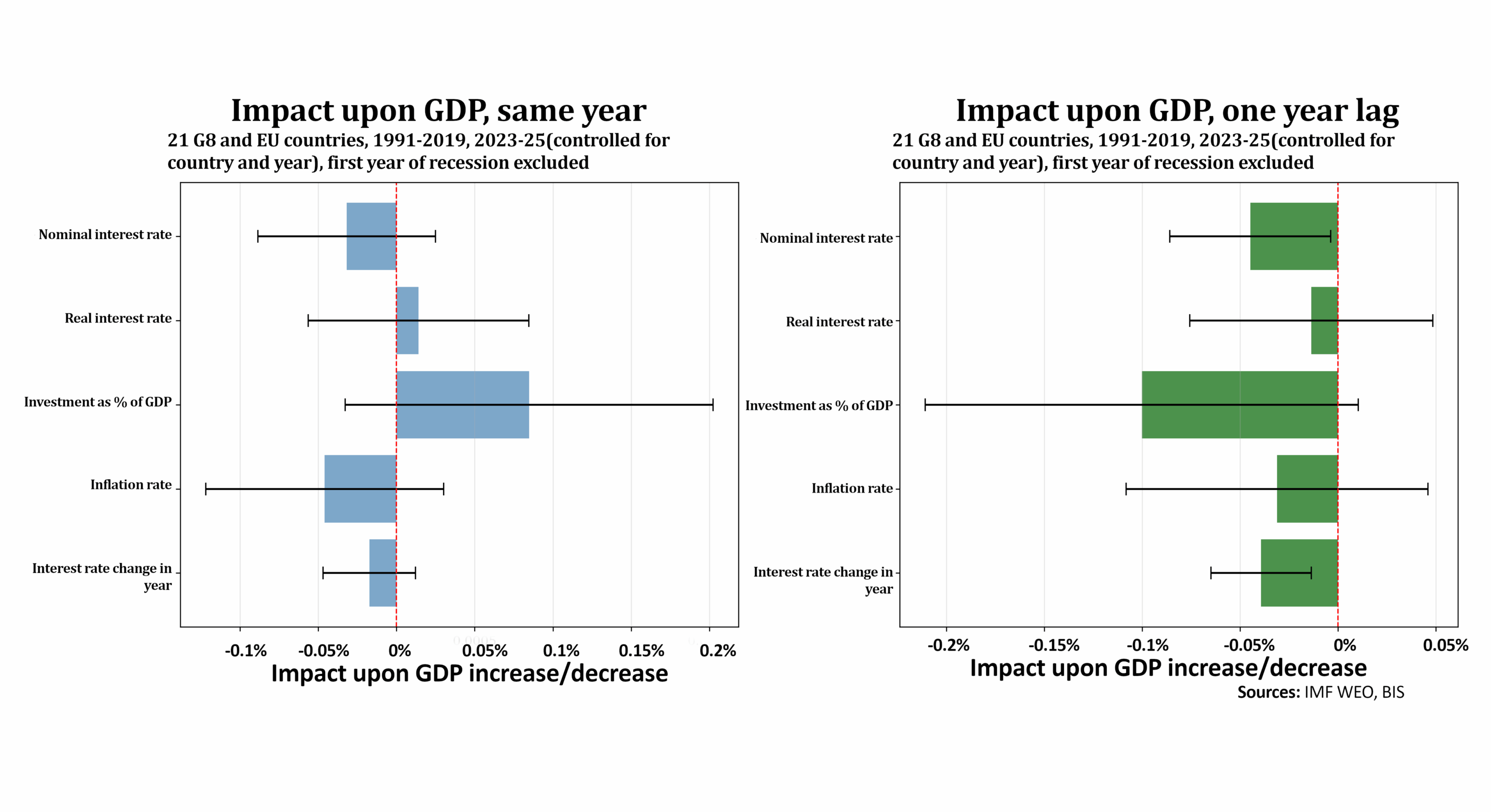

Or, you could argue that there are lots of other variables to consider. Maybe comparing the United States to Croatia, or Hungary to Germany, is not a fair comparison. Or comparing data during the global 2008 crash to years in the recovery afterward is not fair. So we need to control for country and year, and also to look at other data, such as inflation, investment rates and whether the interest rate increased or decreased in that year.

So I did what economists call a “multivariate regression,” asking the computer to look at many variables at once: variations between countries and years (neither shown in the panel below) as well as inflation, investment rates, nominal interest rates, real interest rates and the change in interest rates in a particular year. And I asked for those numbers for the current year as well as a year lag to see the effects:

Show me on the charts above where the “stimulus” is.

The above charts show that no matter how much you tease the data, there’s no way to pull positive GDP numbers from lower interest rates. If you lower interest rates, you’re going to have a slower rate of GDP growth the following year (see bottom right of chart above). While it still remains possible (even if it’s not discoverable in the statistical data) that lowering interest rates may have a tiny positive impact upon GDP, why mortgage your future for a certain larger decrease in GDP the following year?

In the end, there was never any stimulus to the below-market central bank interest rate “stimulus.” And why should lower interest rates stimulate investment? High interest rates draw in foreign investors seeking higher returns, while low interest rates chase capital abroad in search of higher returns.

At this point, you might be saying “That’s just computer mumbo-jumbo. The practical, real-world effect is that people can now afford to buy a house with a low interest rate, right?” Wrong. Lower interest rates just makes the sticker prices of real estate skyrocket, something billionaires love, but in a few years they double the down payment threshold for first-time buyers to save up when the sticker price doubles.

Low interest rates, instead of stimulating economic growth, stimulate a rush to the purchase of assets leveraged with debt in an inflationary economy. These assets, mentioned by Solis-Mullen in his article, include real estate (including vacant and developable lots), stocks and commodities (using ETFs and other vehicles). Low interest rates chase investment away from savings banks (which today have largely devolved into glorified credit card companies) and toward record-high leveraged stock investments and across the financial sector. About 70% of hedge funds use debt for leverage to accelerate profits.

In other words, low interest rates do help the economy of billionaires who leverage debt to inflation, which is why billionaires always say the “economy is stimulated with low interest rates.” Their “economy” is stimulated, and everyone else’s economy doesn’t count. Thus, it should not be a surprise when “Bond King” Bill Gross told Business Insider in 2022 that “The US and other economies cannot stand many more rate increases.” This effect also helps to explain Tobin’s empirical monetary growth research, which relied on corporate and asset valuations and not total output in an economy (a large proportion of which are wages and other assets of the poor and middle class he didn’t measure). What billionaires gain in a low-interest-manipulated environment, the working poor and (to a lesser extent) middle class lose.

Low interest rates have not even stimulated a rush to new housing starts. Even during the boom era of the early 2000s before the 2008 crash, the number of new housing starts never exceeded the number of new units constructed in the early 1970s, a time when the total U.S. population was 30% lower (with a rate of population growth about the same), though household size is now decreasing. You would think that with more people being added to the population and household size shrinking that new housing construction would be more numerous, but housing starts remained flat in the early 2000s compared to past waves of new housing construction and have remained historically low since the Great Recession despite record low interest rates.

And why should low interest rates have spurred housing building? The construction of new houses is not a commodity that can be leveraged until it is actually constructed, but vacant lots are commodities typically purchased on credit. And it’s these vacant lots that skyrocketed in price (along with existing homes) that made new construction no more affordable than before under near-market interest rates. In the end, interest rate-induced skyrocketing real estate prices didn’t spur the building of more houses, but simply made even those developable vacant lots unaffordable. Also, low interest rates didn’t even increase the cumulative payroll of construction workers over the past two decades very much.

It turns out that the lower interest rates just meant more credit was required to buy up the pre-existing stock of now-overpriced housing and not the financing of new construction. Much more credit is needed to finance existing homes if the sale price of the housing to be financed increases dramatically. It takes the same amount of credit to finance one house at $500,000 as it does to finance two houses at $250,000 each. Indeed, with lower interest rates spiking the sticker price of existing homes (increasing the price over-and-above inflation by 65% since 2000), nearly twice the available credit was needed just to finance existing housing units.

Lower interest rates don’t necessarily mean more credit becomes available but that existing credit becomes cheaper. Indeed, since the 2020 pandemic, the Federal Reserve has paid member banks to park their capital at the Fed and not to lend it out and as a result has been operating at a loss. Total consumer credit has increased by about 80% since 2000 (over-and-above inflation), but most of that has been absorbed by financing higher prices for existing housing and more debt-based leverage on Wall Street.

None of that “stimulus” creates any new products, and it in fact starves the economy of credit that would otherwise be put to creative and productive pursuits. The credit-funded central bank accounting gimmicks were merely engineered to enrich the financial class who hoarded already existing assets.

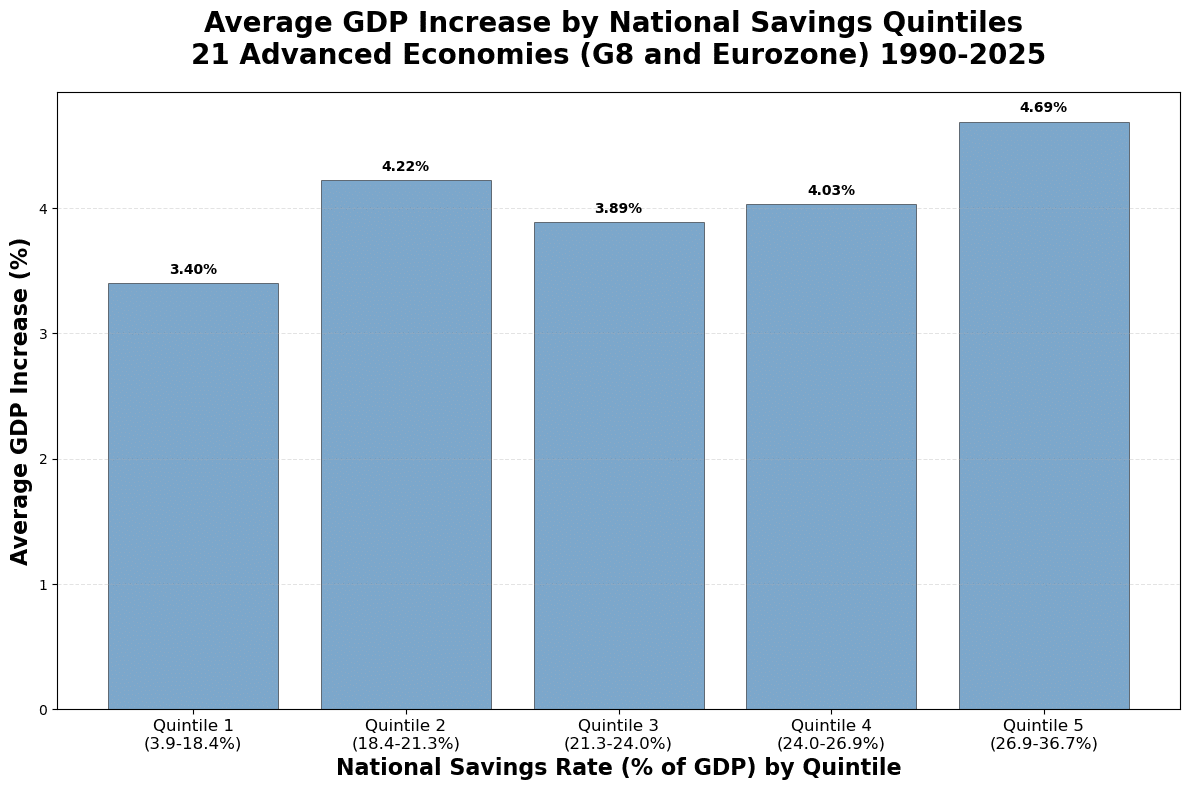

On the other hand, higher savings rates (something that low interest rates can discourage) tends to increase economic growth:

And there, in savings and organic investment, not in artificially suppressed interest rates, are where stronger GDP growth numbers can be found.

So when President Donald Trump tells the Fed it “must lower the RATE, BIG, right now” in his semi-literate TruthSocial posts, he’s ignorantly calling for tanking his own economy. And he’s saying “Brawndo’s got what plants crave. It’s got electrolytes.”