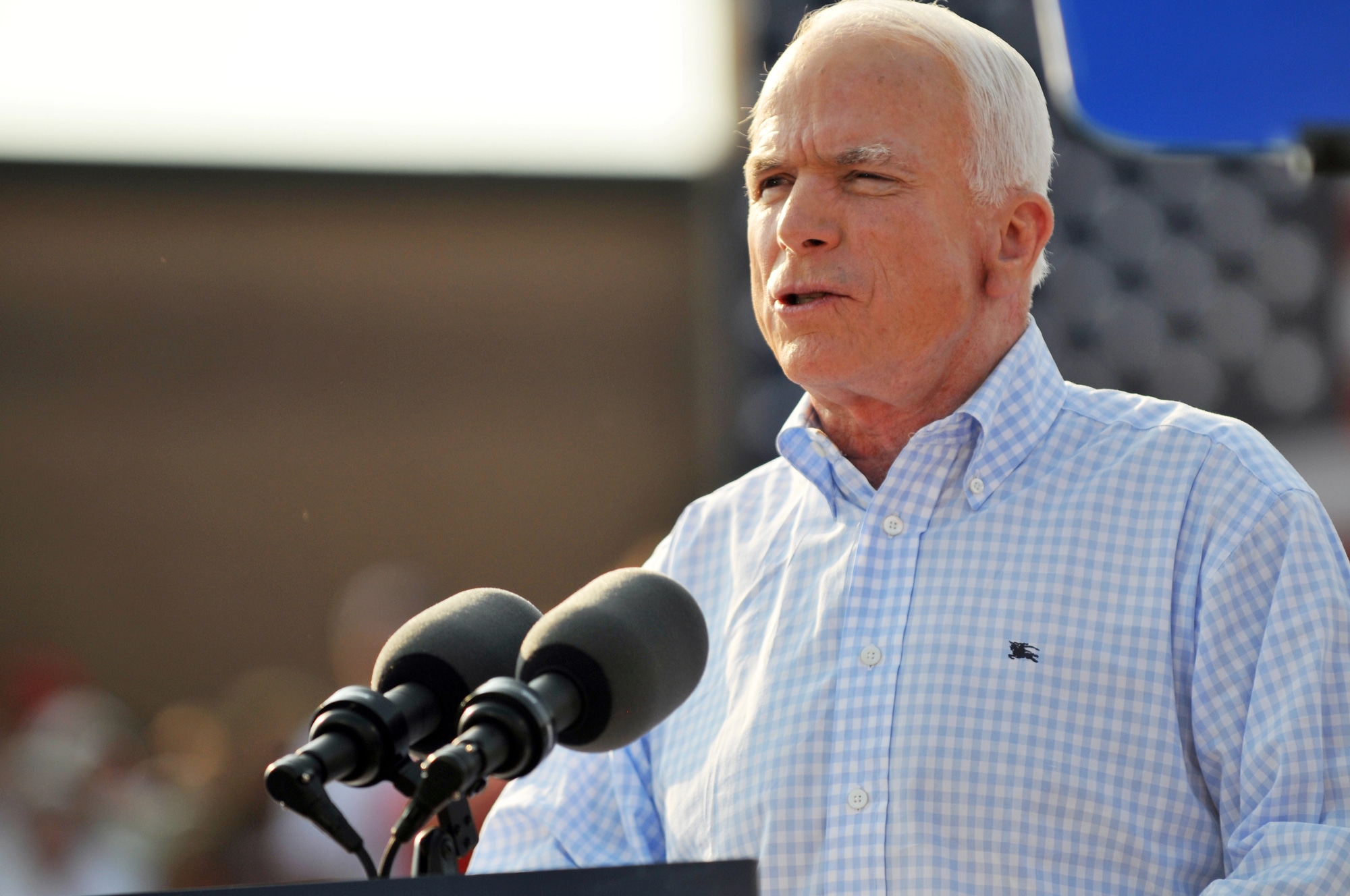

In March 2014, the late Senator John McCain of Arizona stood on the Senate floor and declared that “Russia is now a gas station masquerading as a country.” He repeated this characterization the following year on CNN’s State of the Union, elaborating that Russia was merely “a nation that’s really only dependent upon oil and gas for their economy.” Senator Lindsey Graham (R-SC) echoed this sentiment, calling Russia “an oil and gas company masquerading as a country.” In time, public intellectuals would commonly describe Russia as “gas station with nukes” as a way to dismiss it as an economically hollow petrostate propped up only by natural resources and inherited Soviet nuclear weapons.

This characterization, while rhetorically satisfying, represents a dangerous oversimplification that obscures Russia’s actual economic structure, resilience, and military capabilities. More troublingly, it has fostered a complacent assumption in Western policy circles: that Russia can be easily toppled through economic sanctions and that its threats can be safely dismissed. Three years after the most comprehensive sanctions regime in modern history was imposed following Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine, the evidence tells a different story—one that should give Western policymakers considerable pause.

While Russia’s economy certainly depends significantly on energy exports, characterizing it as merely a “gas station” fundamentally misrepresents the country’s economic structure. Multiple analysts and researchers have challenged McCain’s framing as an oversimplification that has led to flawed strategic assumptions.

President Vladimir Putin directly addressed this characterization at the June 2025 St. Petersburg International Economic Forum, arguing that “Russia’s non-oil-and-gas GDP growth reached 7.2 percent in 2023. In 2024, it grew by 4.9 percent—almost five percent.” He stated that “the outdated image of the Russian economy being solely reliant on oil and gas exports is no longer valid. That belongs to the past—our reality has changed.” Independent Western analysis supports the broader trend the Russian president describes.

Michael Bradshaw, professor of global energy at Warwick Business School, has explained that calling Russia a petrostate obscures important nuances. “Russia has a fairly substantial economy that is not resource-based,” Bradshaw told Charlotte Gifford of World Finance. Gifford noted in her piece that unlike true petrostates like Saudi Arabia where GDP and employment revolve entirely around oil revenues, “Russia has a relatively diversified economy,” with the services sector making up a larger share of GDP than oil and gas.

The numbers bear this out. According to Oxford Energy research, oil and gas revenues accounted for 30% of Russia’s federal budget in 2024, down from nearly 50% in the mid-2010s, suggesting a more diversified economy. Non-oil and gas revenues reached 3,241.214 billion rubles in December 2024. Over the past two years, Putin claims that Russia has generated more income from “agriculture, industry, public works, construction, logistics, services, finance, and information technology’ than from oil and gas.

The assumption that Russia’s supposedly weak economy could be brought to its knees through sanctions has proven spectacularly wrong. Since 2022, Western nations have imposed over 13,000 distinct restrictions on Russia—the most comprehensive sanctions regime ever attempted. The predictions were dire: the International Monetary Fund initially forecast an 8.5% GDP decline for 2022. Yet Russia’s gross domestic product contracted by only 2.1% that year, followed by 3.6% growth in 2023 and 3.9% growth projected for 2024.

A March 2023 report from the Centre for East European and International Studies (ZOIS) in Berlin highlighted that “Russia’s economy has exhibited remarkable resilience” despite the bevy of sanctions imposed on it. The report explained that Russian authorities appeared ready for large-scale sanctions through “a special type of economic management.” For fifteen years, authorities have managed the economy in “permanent crisis mode,” creating “a habit of adopting ad hoc management practices” that proved effective for navigating short-term crises.

Further, the Center for Strategic and International Studies noted in February 2025 that “despite the immense pressure of international sanctions, Russia’s economy has shown remarkable resilience, largely due to its vast natural resources and support from key allies like China.” The report acknowledged that while sanctions have had profound impacts, “three years have also provided Russia with the opportunity to adapt, building alternative financial networks and establishing deeper economic partnerships.”

This resilience matters for more than academic accuracy. The casual discussion of sanctions as a silver bullet policy tool obscures the fact that sanctions are fundamentally a form of economic warfare, and one that has proven less effective than anticipated. When Western policymakers believed sanctions would quickly cripple Russia, they may have been more willing to risk escalation. The reality of Russian economic resilience should prompt a more sober assessment of what economic pressure can achieve and at what cost.

Perhaps the most dangerous aspect of dismissing Russia as merely a “gas station with nukes” is the casualness with which it treats the nuclear weapons part of that equation. Russia possesses approximately 5,580 nuclear warheads, with 1,710 deployed strategic warheads and another 2,670 in reserve. An additional 1,200 retired warheads await dismantlement. Russia’s nuclear triad—consisting of intercontinental ballistic missiles, submarine-launched ballistic missiles, and strategic bombers—remains fully operational and has been modernized significantly over the past two decades.

Western discourse often ignores the calculus of existential threat that governs Russian nuclear doctrine. Russia has consistently stated that it would consider using nuclear weapons if faced with an existential threat to the Russian state. What constitutes such a threat is deliberately ambiguous, but the failure to take this seriously represents a dangerous blind spot in Western strategic thinking. The United States and its allies have provided over $360 billion in military and economic aid to Ukraine since Russia’s 2022 invasion, enabling a proxy conflict that has inflicted significant losses on both the Russian and Ukrainian militaries. From Moscow’s perspective, this represents exactly the kind of strategic pressure that could trigger more decisive responses that could lead to the destruction of the Ukrainian state.

The historical record should caution against complacency. During the Cold War, both sides understood the stakes of nuclear brinkmanship and generally acted with corresponding caution. Today’s more casual attitude toward confrontation with a nuclear-armed power—one partially enabled by the gas station” dismissal represents a troubling departure from the restraint of yore.

Beyond its nuclear arsenal, Russia has made significant advances in conventional military capabilities that have worried Western defense experts. Despite narratives of Russian military incompetence following initial setbacks in Ukraine, Russia has demonstrated technologies and capabilities that the United States and its allies struggle to match.

Russia’s hypersonic weapons program, particularly the Kh-47M2 Kinzhal missile, represents a significant technological achievement. The Kinzhal can reach speeds of Mach 10-12 and has an estimated range of 460-480 km when launched, making it extremely difficult to intercept with current Western air defense systems. While Ukraine has claimed several intercepts using Patriot systems, the broader strategic implications remain concerning. The BBC reported in 2024 that “the hypersonic missiles race is heating up but the West is behind.”

Russia’s electronic warfare capabilities have proven particularly effective in Ukraine. Multiple Western military analysts have highlighted Russia’s sophistication in this domain, with former Department of Defense officer David T. Pyne contending that “Russia has the most capable electronic warfare systems in the world with the longest range and most powerful GPS and radio frequency jammers of any nation.” Russia’s ground-based electronic warfare systems have successfully disrupted Ukrainian communications, GPS guidance systems, and drone operations throughout the conflict.

Russia’s submarine fleet, particularly its Kilo-class and Akula-class vessels, remains a serious threat to NATO naval operations. These submarines have earned nicknames like “Black Holes” for their stealth capabilities.

The characterization of Russia as a gas station with nukes was always more about rhetorical convenience than analytical accuracy. It allowed Western policymakers and commentators to dismiss Russian capabilities, downplay genuine security concerns, and pursue aggressive policies with what seemed like acceptable risk. Three years into the most comprehensive test of these assumptions—the Ukraine conflict and associated sanctions regime—the evidence demands reassessment.

Russia’s economy has proven more resilient and diversified than the gas station narrative suggested. Sanctions, while having limited effects, have not produced the economic collapse that would force Russian capitulation. Meanwhile, Russia’s military capabilities—both nuclear and conventional—demand serious respect rather than dismissal. The country has demonstrated technological advances in hypersonic missile development, electronic warfare, and submarine stealth that challenge Western military superiority in key domains.

The West should learn from three years of miscalculation. Russia is not a gas station. It is a major power with significant economic resilience, technological capabilities, and the world’s largest nuclear arsenal. More importantly, Russia is a great power with valid security concerns and a willingness to use force to protect its traditional sphere of influence.

Underestimating Russia’s strength and resolve, or casually dismissing the genuine risks of escalation, serves no one’s interests. Strategic wisdom demands we see Russia clearly, neither inflating nor dismissing its capabilities, and craft policies accordingly. The alternative—continued escalation based on flawed assumptions—risks catastrophic consequences that no amount of rhetorical satisfaction can justify.

John McCain’s “gas station” quip was politically convenient in 2014, but clinging to it in 2025—seven years after the senator’s death and after billions in failed sanctions and mounting nuclear tensions—isn’t strategy; it’s cognitive dissonance with mushroom clouds on the horizon.