During a January 2026 interview with The New York Times, President Donald Trump was asked whether anything could limit his ability to use the vast military and economic power of the United States as he saw fit. His answer was breathtakingly candid. Trump replied, “Yeah, there is one thing. My own morality. My own mind. It’s the only thing that can stop me.” He added that he doesn’t “need international law” and claimed that he isn’t “looking to hurt people.” These comments came amid reports of U.S. military raids in Venezuela and open discussions in the White House about “a range of options” to force the sale of Greenland.

Morally, a leader claiming to be constrained only by his personal sense of right and wrong should alarm anyone who values the rule of law. But a far more concrete problem exists: the perspective reflects a misunderstanding—or willful rejection—of the constitutional design of the American republic. The U.S. Constitution was deliberately constructed to prevent the very scenario Trump describes, that of a single individual unilaterally dragging the nation into conflict. To prove this, one need look no further than the writings of the Framers and the text of the Constitution itself.

Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution vests Congress with the power “to declare War, grant Letters of Marque and Reprisal, and make Rules concerning Captures on Land and Water.” Congress also holds the purse; no appropriation of money to support an army may be for more than two years. Article II, Section 2 designates the president “Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy,” but only when those forces are “called into the actual Service of the United States.” As Alexander Hamilton explained in Federalist No. 69, the president’s commander‑in‑chief role amounts to “nothing more than the supreme command and direction of the military and naval forces.” Unlike the British monarch, he does not have the power to declare war or raise and regulate armies; those powers “appertain to the legislature.”

The delegates at the Constitutional Convention debated these powers explicitly. The Committee of Detail originally gave Congress the power “to make war.” On August 17, 1787, James Madison and Elbridge Gerry objected that this wording might allow the president to act unilaterally; they moved to substitute the phrase “declare war.” Their amendment passed by an 8–1 vote. Madison later explained that the change reflected a belief that the executive is “the branch of power most interested in war, & most prone to it,” so the Constitution “with studied care, vested the question of war in the Legislature.” Gerry argued that entrusting war to a single office “contradicted the goals of a republic.”

Thomas Jefferson, writing from Paris in September 1789, exulted that the new Constitution had given America “one effectual check to the dog of war, by transferring the power of declaring war from the executive to the legislative body, from those who are to spend, to those who are to pay.” For Jefferson, this change was essential to prevent rulers from dragging nations into wars to serve their own ambitions or to curry favor with special interests. He later wrote to Elbridge Gerry that he “abhor[s] war, and view[s] it as the greatest scourge of mankind,” hoping that the United States would not be drawn into European conflicts.

James Madison went even further. In his Helvidius essays (1793), written during a debate over presidential authority to issue a neutrality proclamation, Madison argued, “In no part of the Constitution is more wisdom to be found than in the clause which confides the question of war or peace to the legislature.” War, he warned, is “the true nurse of executive aggrandizement.” In war, the executive unlocks the public treasure, dispenses offices and honors, and directs a physical force whose laurels will encircle his brow. Because the executive is tempted by ambition, avarice, and the “honorable or venial love of fame,” Madison concluded that “the strongest passions, and most dangerous weaknesses of the human breast” conspire against peace. Consequently, free states have always sought to “disarm this propensity” by denying war‑making powers to a single man.

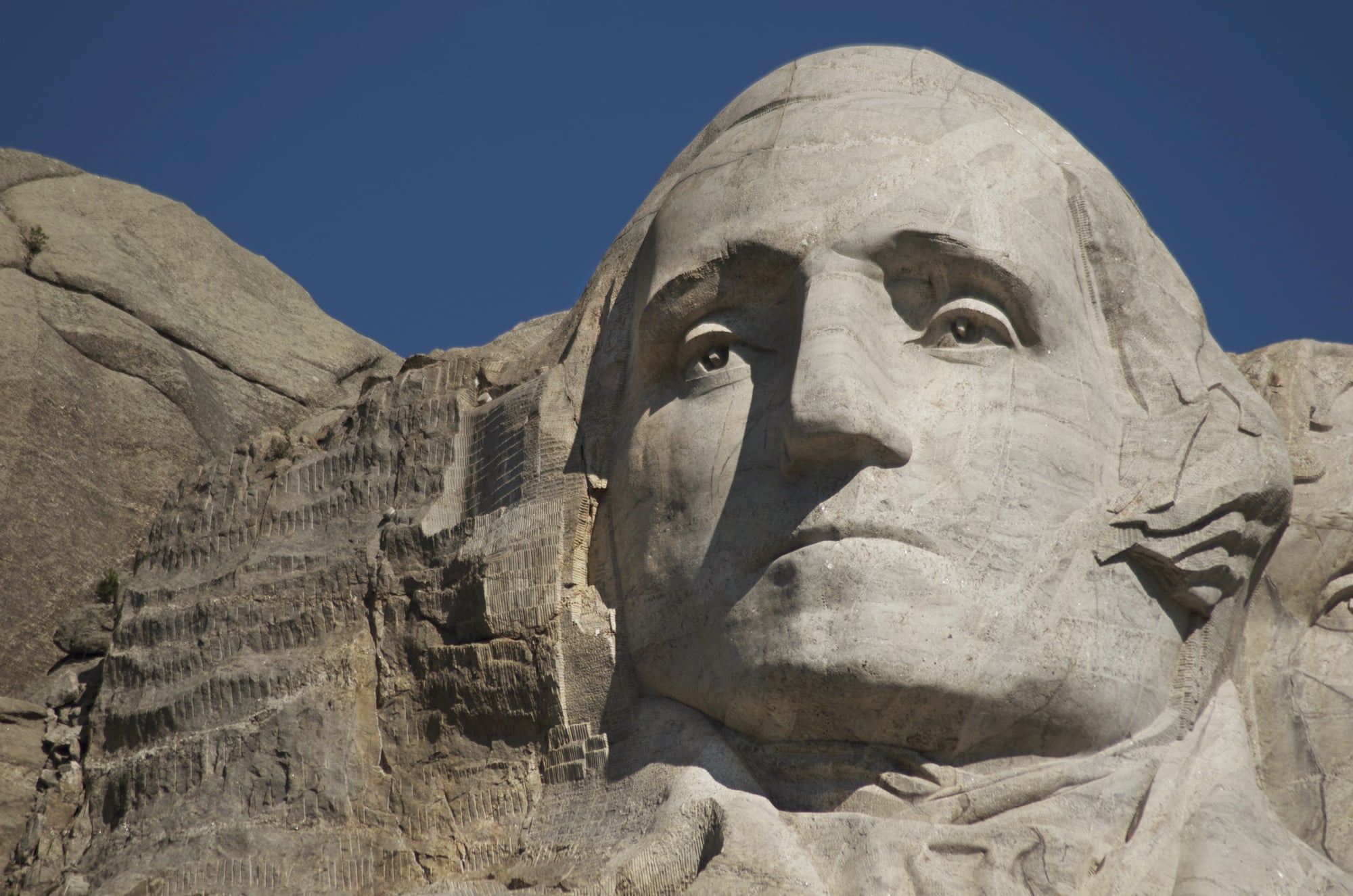

Washington himself, the first person to occupy the office Trump now holds, understood these constraints. In 1793, facing calls to launch an expedition against the Creek Nation, he reminded South Carolina’s governor, “The Constitution vests the power of declaring War with Congress; therefore no offensive expedition of importance can be undertaken until after they shall have deliberated upon the subject, and authorised such a measure.” The father of his country did not consider his own morality a sufficient check—he deferred to Congress before initiating war.

Outside the convention, the ratifying debates reveal a similar consensus. At the Pennsylvania ratifying convention, James Wilson explained that the new Constitution would not “hurry us into war; it is calculated to guard against it. It will not be in the power of a single man, or a single body of men, to involve us in such distress; for the important power of declaring war is vested in the legislature at large.” Because declarations must be made with the concurrence of the U.S. House of Representatives, Wilson concluded that “nothing but our national interest can draw us into a war.”

The logic of the War Powers Clause—placing the decision to go to war in the hands of the people’s representatives—was described by Madison as a structural “bill of rights.” Rejecting concentrated authority was not merely philosophical; the Founders were intimately familiar with abuses by European monarchs. Madison’s warning that the executive is “most interested in war, & most prone to it” came from hard experience. Jefferson’s desire to transfer the war power reflected a belief that those who bear the cost should decide if a war is worth the sacrifice.

Despite the clarity of the Founders’ design, American history after World War II is largely a chronicle of presidents initiating hostilities without formal declarations. Wars from Korea and Vietnam to Kosovo, Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, and Syria proceeded on presidential say‑so. Presidents invoke an inherent commander‑in‑chief power and Congress largely acquiesces.

The War Powers Resolution of 1973 was supposed to restore balance. It requires presidents to notify Congress when hostilities begin and to terminate combat within sixty to ninety days absent legislative approval, but presidents treat it as advisory. Reports are filed that actions are merely “consistent with” the resolution and withdrawal deadlines are ignored. Ending unauthorized wars would require legislation capable of overcoming a presidential veto.

These developments reflect a dynamic Madison predicted: war increases executive power and politicians are reluctant to oppose it. The result is a slow erosion of the “effectual check” Jefferson celebrated.

Congress not only declares war; it controls military funding. The Constitution limits appropriations for the army to two years. This requirement, meant to force regular debate and prevent standing armies, is now largely a formality. Lawmakers authorize funds for long conflicts with little scrutiny and rarely tie money to specific missions or sunset old authorizations. Fear of being labeled soft on defense discourages them from using their leverage.

Madison’s warnings about war were not abstractions. He wrote that war is the “parent of armies” and the “true nurse of executive aggrandizement,” producing debts, taxes, and concentrated power that undermine republican government. The Founders did not romanticize war: Jefferson called it “the greatest scourge of mankind,” Washington urged Americans to “cultivate peace and harmony,” and even Hamilton noted that the president’s war role is command, not initiation.

The Constitution’s designers distrusted concentrated power. As John Adams warned, free government requires trusting no man with authority to endanger liberty. War‑making decisions were therefore placed in Congress to prevent a single individual from unleashing conflict. Trump’s claim that only his morality limits his power inverts this logic. The Constitution does not rely on personal virtue; it constrains presidents through law and legislative deliberation. Madison, Jefferson, and Washington all warned that offensive expeditions require congressional authorization.

To preserve a republic of laws, Congress must reclaim its authority: debate and pass specific authorizations before wars begin, enforce withdrawal deadlines, repeal obsolete AUMFs, and attach sunset clauses to new ones. Deferring to presidential will in matters of war is not patriotic—it is a dereliction of duty. Citizens must also demand adherence to the Constitution; a populace that conflates support for troops with support for intervention will find itself perpetually at war.

The Constitution was crafted to prevent war decisions from resting on presidential morality. Trump’s claim that his mind is the only limit on his power is constitutionally illiterate. The remedy is not a better personality in the Oval Office but a return to the processes Madison, Jefferson, Washington, and their colleagues designed. As Madison reminded Jefferson, if war decisions are left to the executive, “the people are cheated out of the best ingredients in their Government—the safeguards of peace.”