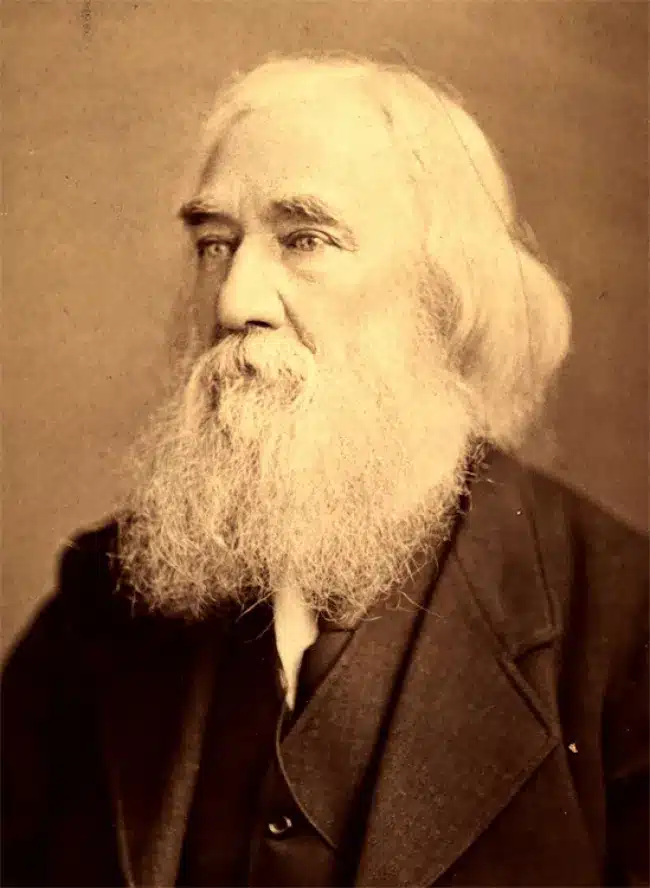

On January 19, 1808, Lysander Spooner entered a world in which slavery, bureaucracy, and government monopolies defined the law. Born near Athol, Massachusetts, he grew up on a farm with parents who refused to surrender to prevailing conventions. His father, Asa, an independent farmer, and his mother, Dolly, nurtured a son who would one day challenge both church and state. He later recalled his mother as one of the “kindest of mothers,” a woman who rejoiced that his antislavery treatise would do much good. When he died in 1887, Spooner was largely forgotten by the mainstream, yet his work as an abolitionist, entrepreneur, lawyer, essayist, natural‐rights theorist, pamphleteer, and political philosopher left an indelible mark on libertarian thought.

Spooner’s early years illustrate a pattern of resistance to entrenched authority. Bound by an agreement to remain on the family farm until he turned twenty‑five, he nonetheless studied classical languages, taught school, and clerked at the Worcester office of deeds. When he read law in 1833 under John Davis and Charles Allen, he confronted a Massachusetts statute requiring non‑college graduates to apprentice for five years. Viewing the rule as protectionist, he printed business cards advertising himself as a lawyer and petitioned the legislature for repeal; with Davis’s support the statute fell, and he was admitted to the bar in 1836. He soon moved west for a real‑estate venture, only to be ruined by the Panic of 1837, after which he drifted back to Athol and then to New York and Boston. Throughout his life he remained an outsider and bachelor. Biographer Charles Shively described him as gruff and impatient with hypocrisy yet admired for his uncompromising moral clarity.

Although trained as a lawyer, Spooner rejected many professional norms. He wrote deist tracts denouncing supernatural authority and condemned licensing rules and state charters as protections for privilege. This tension between personal independence and institutional hierarchy would frame his later battles.

In the 1840s postage rates were high—nearly 18¾ cents to send a letter from Baltimore to New York—and lucrative contracts were riddled with political favoritism. Private carriers secretly transported about a third of all mail, but Spooner, who regarded the postal monopoly as an economic injustice and a constitutional usurpation, refused to operate underground. On January 11, 1844, he wrote to Postmaster General Charles Wickliffe announcing that he would establish a private mail from Boston to Baltimore and would be ready to answer any lawsuit; his advertisement proclaimed that the American Letter Mail Company (ALMC) would agitate and test the right of free competition. Within weeks the ALMC opened offices in Boston, New York, Philadelphia, and Baltimore, delivering mail daily and selling stamps for five cents. Contemporary reports noted that the Articles of Confederation had given Congress the “sole and exclusive right” to establish post offices, but the Constitution omitted that exclusivity. The public embraced the cheaper service; Spooner’s pamphlet argued that congressional postal power no more implied a monopoly than its power to borrow money implied exclusive rights to finance.

Congress defended its monopoly by threatening railroads and steamships that carried ALMC letters and prosecuting Spooner’s agents; each letter constituted a separate offense, enabling prosecutors to burden him with legal fees. A court eventually held that railroads were not liable for passengers carrying letters, yet the pressure took its toll. By March 1845 Congress fixed postage at five cents within three hundred miles and the Post Office adopted private innovations such as prepayment with stamps. Postal deficits quickly turned to surpluses. The ALMC closed in 1851, but its brief existence forced a dramatic reduction in rates and earned Spooner the title “father of cheap postage in America.”

Spooner’s deepest passion was the abolition of slavery. Raised by abolitionist parents, he found it impossible to reconcile human bondage with natural law. His 1845 treatise The Unconstitutionality of Slavery challenged William Lloyd Garrison’s claim that the Constitution was a proslavery document. He argued that law must conform to natural justice and that any statute or compact that violates natural rights is void. Because the Constitution never uses the words “slave” or “slavery” and because English common law and colonial charters did not authorize slavery, there was no lawful basis for the institution. He invoked Lord Mansfield’s Somerset decision to show that slavery required explicit positive law and insisted that tolerating wrongdoing does not make it lawful.

Spooner emphasized that each person has an inalienable right to so much personal liberty as he will use without encroaching upon the equal rights of others. Liberty derives from human nature and cannot be legislated away; therefore, he maintained that slaveholders’ property claims were void and fugitive slaves were entitled to resist. In A Defence for Fugitive Slaves (1850) he urged jurors to acquit those who aided runaways and argued that jurors have both a right and a duty to judge the justice of the law. His later treatise Trial by Jury (1852) extended this claim, contending that juries must be free to assess both facts and law and to nullify unjust statutes. Spooner’s constitutionalism split the abolitionist movement: the Liberty Party embraced his thesis, while Garrisonians excoriated him for legitimizing the Constitution. Frederick Douglass later described the treatise as “tremendously attractive” and credited it with influencing his own shift to an antislavery constitutional reading.

Spooner devoted his later life to articulating the philosophical foundations of liberty. Natural Law; or, the Science of Justice (1882) defines justice as the science of “mine and thine,” encompassing rights of person and property and providing the only basis for peace. Justice tells each person what he may and may not do without infringing another’s rights; it requires everyone to repay debts, return stolen property, make restitution for injuries, and abstain from theft, robbery, arson, murder, or any other crime. Positive law must conform to these natural principles or it is mere force. The treatise laments that throughout history “bands of robbers” have joined together to create governments that enslave the people and keep one class in subordination to another.

His skepticism reached its zenith in the No Treason essays (1867–1870). Writing in the aftermath of the Civil War, he argued that the Constitution has “no inherent authority” because it is a contract to which no living person has consented. Without voluntary consent, taxation and conscription are robbery and slavery. In a famous passage he likened government to a highwayman who steals from you at gunpoint and then pretends to protect you. He concluded that individuals have a right to withdraw allegiance and to form or join voluntary associations, including secessionist communities.

Spooner also applied his natural‑law logic to economics and morals. In Poverty: Its Illegal Causes and Legal Cure (1846) he blamed poverty on state‑granted privileges, monopolies, and banking charters that concentrate wealth. He denounced taxation without consent and the government’s monopoly of money as robbery and advocated free banking based on contracts. His 1875 pamphlet Vices Are Not Crimes was written for a temperance reformer’s book but became an enduring libertarian classic. George H. Smith recounts that Spooner listed “gluttony, drunkenness, prostitution, gambling, prize‑fighting, tobacco‑chewing, smoking, and snuffing, opium‑eating, corset‑wearing, idleness, waste of property, avarice, hypocrisy, &c., &c.” as activities that may be vices but are not crimes because they harm only the actor. Laws punishing vices, he argued, strip individuals of their natural right to pursue happiness by the use of their own property. By drawing a bright line between vice and crime, Spooner sought to protect peaceful autonomy from moralistic legislation.

Spooner’s writings were largely ignored in his day, and he eked out a living from small law cases and pamphleteering. After the Civil War he grew disillusioned with what he saw as the expanding power of the federal government. Yet in the twentieth century his ideas resurfaced in libertarian thought. Economist Murray N. Rothbard hailed his portrayal of the state as a robber band as “perhaps the most devastating ever written,” and legal theorist Randy E. Barnett argues that Spooner “deserves a place of honor” for the brilliance with which he defended his principles. Helen Knowles notes that he never strayed from his libertarian commitments. His ideas continue to inspire jury‑nullification activists, critics of monetary monopolies, and those advocating postal privatization, secession, and constitutionally limited government.

At a personal level he remained an outsider. He lived for years in a small Boston apartment near the Athenaeum, writing prolifically, and died alone in 1887. He never called himself an anarchist, yet historians now place him within the American individualist tradition. His mentee Benjamin Tucker carried his individualist anarchism into the late nineteenth century. The Fully Informed Jury Association invokes his trial‑by‑jury essay to educate jurors on their power to nullify unjust laws, and postal reformers still cite his entrepreneurial example. Even debates over secession, originalism, and victimless crimes bear his imprint. By coupling moral argument with practical action, he showed that one person, armed with principled convictions, can force a leviathan to bend.

Lysander Spooner’s life was a relentless confrontation with every institution that claimed arbitrary authority. From his farmboy rebellion against bar licensing laws to his entrepreneurial assault on the postal monopoly, from his constitutional demolition of slavery to his philosophical repudiation of social contracts, he consistently applied a single measure: justice is grounded in natural rights, not in the decrees of politicians. He demanded that individuals judge law by whether it protects or violates the equal freedom of all, and he refused to accept that wrongs become right through majority vote or custom. In celebrating his birthday, we recall a man who not only spoke but acted upon his convictions, illustrating that moral courage and intellectual clarity can challenge even the most entrenched systems. His legacy endures in every movement that seeks to secure liberty through principle rather than power, and his writings remind us that freedom is not a gift from government but an inherent right that no government can legitimately take away.