The people performing those mind-boggling contortions to justify, on libertarian grounds, state violence against migrants without papers—restrictatarians, I call them—cite a 1994 article by Murray Rothbard (1926-1995) in support of their double-jointed acrobatics. Rothbard was correct about many things, but a position is not correct merely because Rothbard held it. I expect no disagreement over that.

As a general matter, Rothbard’s importance to the shaping of the modern libertarian movement needs no documentation. He was accomplished in economics, social theory, and history. In his time, he was known as Mr. Libertarian, the guardian of the plumb line. (He was also my friend and, informally, my teacher.) His words carry much weight for people who love liberty. It’s therefore appropriate to show why, in this case, in 1994, Rothbard was stunningly wrong about immigration, or the freedom to move.

The article is “Nations by Consent: Decomposing the Nation-State” (Journal of Libertarian Studies, Fall 1994). In the wake of the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Rothbard wrote:

The question of open borders, or free immigration, has become an accelerating problem for classical liberals. This is first, because the welfare state increasingly subsidizes immigrants to enter and receive permanent assistance, and second, because cultural boundaries have become increasingly swamped. I began to rethink my views on immigration when, as the Soviet Union collapsed, it became clear that ethnic Russians had been encouraged to flood into Estonia and Latvia in order to destroy the cultures and languages of these peoples. Previously, it had been easy to dismiss as unrealistic Jean Raspail’s anti-immigration novel The Camp of the Saints, in which virtually the entire population of India decides to move, in small boats, into France, and the French, infected by liberal ideology, cannot summon the will to prevent economic and cultural national destruction. As cultural and welfare-state problems have intensified, it became impossible to dismiss Raspail’s concerns any longer.

What might Rothbard be saying here? Note this: “I began to rethink my views on immigration when, as the Soviet Union collapsed, it became clear that ethnic Russians had been encouraged to flood into Estonia and Latvia in order to destroy the cultures and languages of these peoples.” This has been quoted many times. Sometime in the past, Rothbard explained, a horde of ethnic Russians was sent into the Baltic states with bad intent. We must conclude that unrestricted immigration is bad. QED. Really?

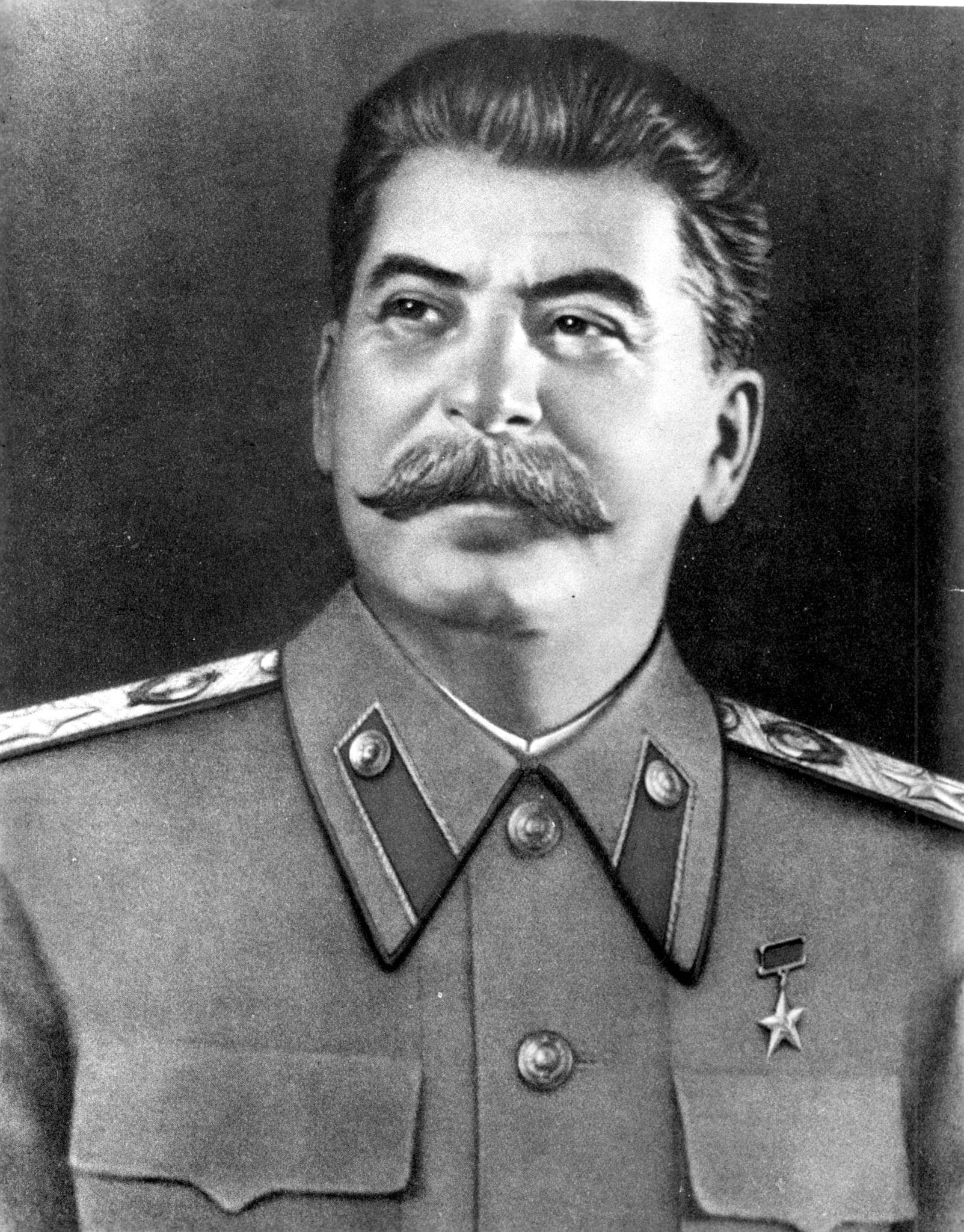

Rothbard further wrote that the fact of Baltic Russification became clear to him as—meaning not until?—the Soviet Union was falling apart in the late ’80s and early ’90s. But that cannot be. Rothbard was a student of Russian and Soviet history, so he must have been aware of the past episodes of Russification under the czars and Stalin’s Soviet regime long before the Soviet Union’s disintegration. Furthermore, he must have known that one of its primary objectives was cultural transformation. None of this could have been news to Rothbard when he wrote his article.

So why would Rothbard lead us to believe that he did not know about Russification until the early ’90s? I hate to say this, but perhaps at that moment, he needed a respectable-sounding excuse for announcing his change of mind about free immigration.

Here is how Gemini replied to my question about Rothbard’s statement (emphasis added):

The mass migration of ethnic Russians into the Baltic states occurred during the Soviet occupation (1944–1990), not after they gained independence in 1991…. After regaining independence, the Baltic states experienced a net outflow of ethnic Russians, not a “flood” into them. Many ethnic Russians left the Baltic states to return to the Russian Federation in the early 1990s.

Gemini added that the “intensive” Soviet Russification of the Baltics “became a major international and internal issue from the 1950s through the 1980s.” (For scholarly treatments of Stalin’s Russification of the Baltics, see, for example, this and this. On the outflow of Russians from the Baltic states after independence, see this.)

The Soviet Union occupied the Baltic states, including Lithuania, in 1940 under the terms of the Nazi-Soviet Ribbentrop-Molotov Cocktail Treaty. Stalin lost control of those states to the Nazis, but reoccupied them when the Nazis were defeated.

ChatGPT agreed with Gemini and added details:

- After annexing the Baltic states in 1940 and again after the Nazi occupation (1941–1944), the Soviet authorities encouraged large-scale migration of ethnic Russians and other Soviet citizens into the Baltic republics.

- This migration was part of broader industrialization and urbanization policies. Factories and military installations were established, and workers were brought in from other parts of the USSR to fill labor shortages.

- Though Soviet leaders often justified this as economic modernization, historians widely recognize that it also served political aims—to integrate the Baltic states more tightly into the USSR and dilute local national identities.

In other words, the episode that Rothbard referred to had nothing to do with free immigration or open borders at all. It was Soviet settler colonialism. The Baltic states did not become captives of the Soviet Union after an influx of subversive ethnic Russian immigrants. On the contrary, the influx of ethnic Russians was made possible by the Soviet annexation. Stalin exiled Baltic people to Siberia to make room and open jobs for the Russians. Latvia, Estonia, and Lithuania could not have closed their borders to the ethnic Russians between 1940 and 1990 because those countries, as captive nations, could have had no policies independent of the Soviet Union.

Again, that was classic settler colonialism, a threat that Americans do not face. How in the world did Soviet settler colonialism in the 1940s prompt Rothbard, in 1994, to change his mind about free immigration? It had nothing to do with immigration. Zip. Zilch. Bupkis. As Rothbard might have put it, his case against freedom is a floperoo.

Even though Rothbard’s history is incorrect, a takeaway could run as follows: a hostile state might send a significant portion of its population, armed and dangerous, into a neighboring state for some malign purpose. Such an influx of belligerents, of course, would resemble a military invasion and should be treated accordingly. That’s not immigration. That’s war.

However, what if an overwhelming mass of migrants just wanted to find jobs, rent apartments, buy homes, engage in all other sorts of trade, and so on? As the economist and my friend Gene Epstein points out, that’s too unlikely a scenario to be taken seriously.

Here’s why. The migrants would want to know that the host country had ample job openings and affordable rents. They wouldn’t want to leave familiar environs to become jobless, homeless, and hungry in a strange place where they’d have difficulty speaking the language: strangers in a strange land. Remember, many migrants come to America to earn money to send home to their families. Those remittances dwarf foreign aid. As more workers moved, however, conditions could become less and less amenable (unless economic growth from the last wave of immigrants boosted economic growth). As is their wont, new migrants would then write home to tell their friends and family that now was not the time to come: job openings were scarce, wages weren’t extraordinary, and the cost of living was high. So-called illegal immigration into the United States has waxed and waned with the job outlook. Thus, the chance of an economically motivated, sudden, overwhelming mass migration is practically nil.

Mightn’t they come for the welfare, as Rothbard warned in 1994? Not if they couldn’t qualify for several years—as they cannot for the most part in the United States. Moreover, Alex Nowrasteh of the Cato Institute has found that, even if current welfare laws in the U.S. remained on the books, the fiscal effects of immigration on the state are about neutral when we factor in the taxes immigrants pay through their high rates of employment. When we include the value they produce in those jobs—almost entirely in the private sector!—the U.S. economy comes out ahead.

Using the welfare state to justify restricting the liberty of individuals born on the far side of a political boundary is a textbook example of Ludwig von Mises’s “critique of interventionism,” according to which, the problems that government interference with the free market inevitably creates ostensibly necessitate more government interference. How will we ever get rid of the welfare state if it is sheltered from the predictable stresses and strains?

At any rate, regardless of immigration, the welfare state ought to be abolished. Forcing the productive to support the unproductive is unjust. Help ought to be left to voluntary charity. (Aside: does anyone believe the restrictatarians would change their minds about open borders if the welfare state were abolished?)

A state powerful enough to be prepared for all manner of imagined emergencies, no matter how unlikely, should be too much state for any libertarian’s taste.