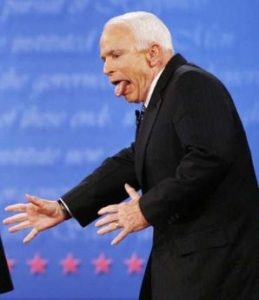

Is this really supposed to be a thing: social pressure to “honor” — and never diminish — John McCain like he was some kind of hero? He wasn’t. He was a terrible man. He was a liar, a warmonger, a servant of the neoconservatives, who pushed for every bloody and disastrous policy he could get behind, from Iraq War I and the 1990s blockade and bombing campaign to the wars in the Balkans to Iraq War II and then its “surge,” Afghanistan and its “surge,” backing al Qaeda in their wars in Libya and Syria (remember it was his buddies in the Northern Storm Brigade who sold Steven Sotloff to ISIS), then the subsequent Iraq War III to drive ISIS back out of western Iraq again. He was bad on Iran, bad on Yemen, bad on Korea, bad on Russia, bad on everything. Now he’s finally not anymore.

Is this really supposed to be a thing: social pressure to “honor” — and never diminish — John McCain like he was some kind of hero? He wasn’t. He was a terrible man. He was a liar, a warmonger, a servant of the neoconservatives, who pushed for every bloody and disastrous policy he could get behind, from Iraq War I and the 1990s blockade and bombing campaign to the wars in the Balkans to Iraq War II and then its “surge,” Afghanistan and its “surge,” backing al Qaeda in their wars in Libya and Syria (remember it was his buddies in the Northern Storm Brigade who sold Steven Sotloff to ISIS), then the subsequent Iraq War III to drive ISIS back out of western Iraq again. He was bad on Iran, bad on Yemen, bad on Korea, bad on Russia, bad on everything. Now he’s finally not anymore.

There’s really no way to give justice in a short summary to the amount of damage McCain’s presence in the U.S. Senate has caused for the people of the world, especially in the era of this century’s terror wars. He was as important as Bill Kristol or Paul Wolfowitz in pushing us into Iraq War II and his constant pressure from the right has been an extremely important part of each and every one of the wars and the various escalations of them ever since then. With Lindsey Graham and a rotating cast of third “Amigos,” such as Joe Lieberman and Kelly Ayotte, McCain has always been Washington’s most reliably hawkish bloodmonger on every issue.

Remember that time when McCain claimed Iran was training al Qaeda in Iraq, when what he meant was that he personally had taken the lead in having U.S. forces get rid of Saddam for the Ayatollah and fight a five-year civil war on behalf of Iran’s friends in the Dawa Party and Badr Brigade the whole damn war long — against al Qaeda there as well — and had no idea what the hell he was talking about and Lieberman had to interrupt before he made it any worse?

Now he’s died of lethal brain cancer just like the depleted uranium babies of Fallujah and Ramadi. And we’re supposed to be more upset about his death than theirs.

By the way, McCain was only rich because his criminal drug addict-yet immune from prosecution wife was born into Arizona’s state alcohol cartel.

And don’t give me this shit about Vietnam. Just because McCain was captured by the NVA when he got shot down in an attempt to bomb them to death in an aggressive war doesn’t make him a hero.

From Tim Dickinson’s profile:

Sipping scotch and reflecting on the fire aboard the Forrestal, McCain sounded like the peaceniks he would pillory after his return from Hanoi. “Now that I’ve seen what the bombs and napalm did to the people on our ship,” he told Apple, “I’m not so sure that I want to drop any more of that stuff on North Vietnam.” Here, it seemed, was a frank-talking warrior, one willing to speak out against the military establishment in the name of truth.

But McCain’s misgivings about the righteousness of the fight quickly took a back seat to his ambitions. Within days, eager to get his combat career back on track, he put in for a transfer to the carrier USS Oriskany. Two months after the Forrestal fire — following a holiday on the French Riviera — McCain reported for duty in the Gulf of Tonkin.

Only after explicitly coming to terms with what a crime it is to kill humans with napalm did he get shot down while going back to do it again.

And would you be surprised to find out that McCain embellished the story of his captivity there for personal gain?

According to Dramesi, one of the few POWs who remained silent under years of torture, McCain tried to justify his behavior while they were still prisoners. “I had to tell them,” he insisted to Dramesi, “or I would have died in bed.”

Dramesi says he has no desire to dishonor McCain’s service, but he believes that celebrating the downed pilot’s behavior as heroic — “he wasn’t exceptional one way or the other” — has a corrosive effect on military discipline. “This business of my country before my life?” Dramesi says. “Well, he had that opportunity and failed miserably. If it really were country first, John McCain would probably be walking around without one or two arms or legs — or he’d be dead.”

Once the Vietnamese realized they had captured the man they called the “crown prince,” they had every motivation to keep McCain alive. His value as a propaganda tool and bargaining chip was far greater than any military intelligence he could provide, and McCain knew it. “It was hard not to see how pleased the Vietnamese were to have captured an admiral’s son,” he writes, “and I knew that my father’s identity was directly related to my survival.”

But during the course of his medical treatment, McCain followed through on his offer of military information. Only two weeks after his capture, the North Vietnamese press issued a report — picked up by The New York Times — in which McCain was quoted as saying that the war was “moving to the advantage of North Vietnam and the United States appears to be isolated.” He also provided the name of his ship, the number of raids he had flown, his squadron number and the target of his final raid.

THE CONFESSION

In the company of his fellow POWs, and later in isolation, McCain slowly and miserably recovered from his wounds. In June 1968, after three months in solitary, he was offered what he calls early release. In the official McCain narrative, this was the ultimate test of mettle. He could have come home, but keeping faith with his fellow POWs, he chose to remain imprisoned in Hanoi.

What McCain glosses over is that accepting early release would have required him to make disloyal statements that would have violated the military’s Code of Conduct. If he had done so, he could have risked court-martial and an ignominious end to his military career. “Many of us were given this offer,” according to Butler, McCain’s classmate who was also taken prisoner. “It meant speaking out against your country and lying about your treatment to the press. You had to ‘admit’ that the U.S. was criminal and that our treatment was ‘lenient and humane.’ So I, like numerous others, refused the offer.”

“He makes it sound like it was a great thing to have accomplished,” says Dramesi. “A great act of discipline or strength. That simply was not the case.”

In fairness, it is difficult to judge McCain’s experience as a POW; throughout most of his incarceration he was the only witness to his mistreatment. Parts of his memoir recounting his days in Hanoi read like a bad Ian Fleming novel, with his Vietnamese captors cast as nefarious Bond villains. On the Fourth of July 1968, when he rejected the offer of early release, an officer nicknamed “Cat” got so mad, according to McCain, that he snapped a pen he was holding, splattering ink across the room.

“They taught you too well, Mac Kane,” Cat snarled, kicking over a chair. “They taught you too well.”

The brutal interrogations that followed produced results. In August 1968, over the course of four days, McCain was tortured into signing a confession that he was a “black criminal” and an “air pirate.”

“John allows the media to make him out to be the hero POW, which he knows is absolutely not true, to further his political goals,” says Butler. “John was just one of about 600 guys. He was nothing unusual. He was just another POW.”

McCain has also allowed the media to believe that his torture lasted for the entire time he was in Hanoi. At the Republican convention, Fred Thompson said of McCain’s torture, “For five and a half years this went on.” In fact, McCain’s torture ended after two years, when the death of Ho Chi Minh in September 1969 caused the Vietnamese to change the way they treated POWs. “They decided it would be better to treat us better and keep us alive so they could trade us in for real estate,” Butler recalls.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zO0mHEJyC3Y&feature=youtu.be

Now we have humanity minus McCain. And the future is a little brighter.