Tuesday, April 13, 2010

The Greyhound Station Gulag

FEMA camp survivor: Businessman Abdulrahman Zeitoun, a naturalized U.S. citizen from Syria, stands outside the New Orleans Greyhound station that was converted into an open-air detention center following Katrina. Zeitoun was imprisoned under FEMA jurisdiction after being arrested for “trespassing” on his own property.

New Orleans resident Abdulrahman Zeitoun was with three friends in the living room when the looters came. Like most of the armed criminal gangs afflicting the city in Katrina’s wake, the marauders who confronted Mr. Zeitoun wore government-issued costumes.

Before the day’s end, the Syrian-born U.S. citizen — who had spent days paddling through the flooded streets in a canoe, rendering what aid he could to people trapped in their ruined homes — would be confined in a makeshift detention camp modeled after the notorious facility in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba.

No formal criminal charges were filed against Zeitoun. When he protested the denial of his due process rights and rudimentary decencies of living, he was told by the guards that he was under the jurisdiction of FEMA (the Federal Emergency Management Agency) — which meant that he was somebody else’s problem.

If it hadn’t been for an encounter with a Christian missionary ministering to the prisoners — a man Zeitoun believes was sent in literal answer to prayer — it’s likely that he and at least one of his friends, a fellow Syrian-American, would still be prisoners of the Department of Homeland Security.

Zeitoun was raised in the Syrian coastal town Jableh as part of a financially successful and well-regarded family. After migrating to New Orleans, Zeitoun found work with a local building contractor. Blessed with a strong work ethic and uncanny entrepreneurial instinct, he created a small house-painting business that quickly grew to include ownership of several rental properties — including the house from which he was kidnapped under the color of government “authority” the morning of September 6, 2005.

Just before Katrina hit the city, Zeitoun sent his wife Kathy and their four children to stay with friends in Houston. He remained behind to safeguard the house, look after the rental properties, and help wherever he could. On several occasions while he was rendering aid to stranded neighbors, Zeitoun encountered patrol craft carrying police or military personnel, who were too busy maintaining an intimidating facade to lend assistance.

Prior to his arrest, the only direct contact Zeitoun had with “authority” came in the form of a visit by “rescue” personnel in a government helicopter. At the time, Zeitoun was setting up his tent in the back yard of his home.

After several attempts by the weary Good Samaritan to communicate that he was fine and intended to stay, “one of the men in the helicopter decided to drop a box of water down to him,” recounts Pulitzer Prize-winning author David Eggers in his book Zeitoun. He tried to wave them off again, “to no avail. The box came down, and Zeitoun leapt out of the way before it knocked the tent flat and sent plastic bottles everywhere.” The government employees, having “helped” the resident by demolishing his shelter, flew away to impart similar assistance elsewhere.

While Zeitoun was helping his neighbors, the police — including the officers who would materialize in his living room to arrest him on suspicion of “looting” — were helping themselves to whatever they wanted.

***

***

New Orleans Police Officer Donald Lima, who was part of the team that arrested Zeitoun, spent much of his time as a government-licensed looter and swapping the plundered property with National Guard units.

“In exchange for gasoline, Lima and other New Orleans police officers broke into convenience stores and took cigarettes and chewing tobacco,” recalls Eggers. “A majority of the National Guardsmen, Lima said, chewed tobacco and smoked Marlboros, so this arrangement kept both sides well supplied. Lima considered the looting a necessary part of the mission.” The gasoline was needed for official business, he maintained, as well as “to power his home generators.”

When Guardsmen couldn’t provide him with gas, “Lima siphoned fuel from cars and trucks. His throat was sore from all the gas-siphoning he did after the storm, he said.”

Ralph Gonzalez, an officer from Albuquerque, New Mexico, also took part in Zeitoun’s arrest. He was among the out-of-state officers who arrived five days after the storm. “We thought we were in a third-world country,” he told Eggers, which is why he and his fellow cops spent most nights cowering in a secure location while the people they were supposedly serving and protecting were being preyed on by armed criminals.

Lima and Gonzalez were two of the six uniformed heroes who eagerly stormed into Zeitoun’s property on September 6, arresting the businessman and three friends on suspicion of looting (that is, stealing without official permission) and dealing drugs.

When identification was demanded, Zeitoun complied, but the soldier who issued the demand didn’t deign to look at the card. The invaders — five men and a female National Guard officer — didn’t collect evidence or secure the “crime scene.” The four civilians were marched out to a motorboat that conveyed them through flooded streets to an intersection that provided a patch of high ground. Once there, they were surrounded by a phalanx of armed men in body armor.

As two armed thugs performed the familiar profane recital (“Stay there, motherf****r!” “Don’t move, a*****e!”), Zeitoun was thrown face-down in the stygian mud and his hands were zip-tied behind his back. A few minutes later he found himself being processed into a makeshift military detention facility at the local Greyhound station.

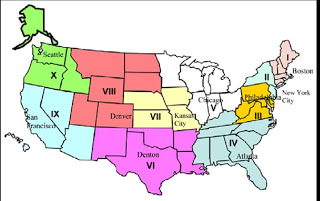

Insta-gulags — coming soon to a town near you? The continental United States, as divided into FEMA districts. Just something to think about.

“Camp Greyhound” was described by USA Today as an “outpost of law and order” amid the entropic violence of post-Katrina New Orleans. A more suitable description would be “Gitmo North.”

Camp Greyhound, which at one point held 1,200 prisoners, “looked precisely like the pictures … of Guantanamo Bay,” writes Eggers. “Like that complex, it was a vast grid of chain-link fencing with few walls, so the prisoners were visible to the guards and each other. Like Guantanamo, it was outdoors, and there appeared to be nowhere to sit or sleep. There were simply cages and the pavement beneath them.”

After being stripped and subjected to a body cavity search, Zeitoun was detained with his friends in one of the facility’s “pods.” For the next three days and nights, “the pavement would be their bed, their open-air toilet would be their bathroom, and the steel rack would be the seat they could share,” continues Eggers.

As Americans of Arab ancestry, Zeitoun and his friend Nasser Dayoob received particular attention from their captors, who insisted: “You guys are al-Qaeda.”

In addition to being denied blankets or even a decent sleeping surface, the prisoners — who included Todd Gambino, one of Zeitoun’s tenants, and a man named Ronnie who had sought shelter after the flood — were bathed in the blinding glare of a floodlight after nightfall.

After the first sleepless night, another prisoner was introduced into the mix, an oddly jovial guy called Jerry. Curiously, Jerry focused most of his attention on Zeitoun and Nasser, and seemed strangely eager to solicit negative opinions about the Bush administration, U.S. foreign policy, and the military.

One didn’t have to look for potting soil caked between his toes in order to recognize that Jerry was a plant.

For Zeitoun and the other prisoners, the Camp Greyhound experience was one of constant tedium occasionally leavened with torment. In time-honored fashion, the guards exploited any excuse to inflict exemplary “discipline” on the detainees, most of whom had been arrested for violating curfew or similar petty matters.

“Always the procedure was the same,” narrates Eggers, “a prisoner would be removed from his cage and dragged to the ground nearby, in full view of the rest of the prisoners. His hands and feet would be tied, and then, sometimes with a guard’s knee on his back, he would be sprayed directly in the face” with pepper spray. “If the prisoner protested,” continues Eggers, “the knee would dig deeper into his back. The spraying would continue until his spirit was broken. Then he would be doused with [a] bucket and returned to his cage.”

These ritual acts of sadism, Eggers observes, were “born of a combination of opportunity, cruelty, ambivalence, and sport.” They were intended to torment the other prisoners, most of whom — like Zeitoun — were made nauseous with suppressed rage by the spectacle of helpless men being tortured.

The victims included one disturbed man with the intellectual and emotional capacity of a child who was “punished” because he displayed the irrepressible symptoms of mental illness.

“Under any normal circumstances [Zeitoun] would have leapt to the defense of a man victimized as that man had been,” observes Eggers. “But that he had to watch, helpless, knowing how depraved it was — this was punishment for the others, too. It diminished the humanity of them all.”

After three days in the Greyhound station gulag, Zeitoun and his friends were transferred to the Elayn Hunt Correctional Center. (Jerry, of course, wasn’t with them.) Following another strip-search, Zeitoun and Nasser — the two Syrian-Americans — were separated from the other innocent prisoners and confined in a maximum security cell.

For more than two weeks they would be abused, neglected, humiliated, insulted and subjected to a visit from a Gitmo-style “Extreme Repression Force” (ERP). Clad in black riot gear, wielding ballistic shields, batons, and other weapons, the ERP “burst in as if [Zeitoun] were in the process of committing murder,” writes Eggers. “Cursing at him, three men used their shields to push him to the wall. As they pressed his face against the cinderblock, they cuffed his arms and shackled his legs.”

After heroically subduing an unresisting man — who by this time was dealing with an infected foot and a mysterious kidney ailment — the ERP tore apart the cell before forcing the victim to strip and submit to another body cavity search.

While Zeitoun was suffering in Louisiana, his wife and children in Texas were convinced he was dead. He had never been permitted to contact his wife following his arrest, and Kathy wasn’t able to find any trace of him. Before Katrina hit, the two of them would occasionally speak about the potentially dire consequences for an Arab-American who found himself in police custody. They were aware of many instances in which “a Muslim came to be suspected by the U.S. government, and, under the president’s current powers, U.S. agents were allowed to seize the man from anywhere in the world and bring him anywhere in the world, without ever having to charge him with a crime.”

“How different was Zeitoun’s current situation?” Eggers reflects. “He was being held without contact, charges, bail, or trial…. Zeitoun did not entertain such thoughts lightly. They went against everything he knew and believed about his adopted country. But then again, he knew the stories. Professors, doctors, and engineers had all been seized and disappeared for months and years in the interest of national security. Why not a house painter?”

On September 19, Kathy’s cell phone rang.

“Is this Mrs. Zeitoun?” asked an unfamiliar male voice, mis-pronouncing the last name.

“Yes,” Kathy replied in a voice tremulous with dread.

“I saw your husband,” the voice informed her. “He’s okay. He’s in prison. I’m a missionary. I was in Hunt, the prison up in St. Gabriel. He’s there. He gave me your number.”

When Kathy began to barrage him with questions, the missionary hastily explained: “Look, I can’t talk to you any more. I could get in trouble. He’s okay, he’s in there. That’s it. I’ve got to go.”

Deprived of any source of hope except for prayer, Zeitoun had pleaded with God to send a messenger. Shortly thereafter a middle-aged black man visited his cell — a missionary who was distributing Bibles and praying with the inmates. At no small risk to himself — remember, we live in an era when defense attorneys who pass along notes from terrorist suspects can be sent to prison themselves — this man of God honored Zeitoun’s request to contact his wife and family.

Ten more days would pass before Kathy succeeded in freeing her ailing husband. After dashing back to New Orleans, she contacted the court to learn where Zeitoun’s pre-trial hearings would take place.

“Oh, we can’t tell you that,” sniffed the functionary on the other end of the phone. “That’s privileged information.”

“Privileged for who? I’m his wife!” exclaimed Kathy.

“I’m sorry, that’s private information,” replied the drone.

“It’s not private! It’s public!” Kathy insisted. “That’s the point! It’s a public court!”

Zeitoun’s courtroom experience followed the same Kafka-inspired script. Charged with “looting” his own house, Zeitoun was given $75,000 bail — but denied a phone call to arrange for someone to bail him out.

Eventually, with the help of an attorney and a CNN producer, Kathy was able to contact her husband and post bail. His friends weren’t as fortunate: Nasser, Todd, and Ronnie were imprisoned for five, six, and eight months, respectively, before the charges against them were dropped.

Once he was free, Zeitoun’s health improved immediately. The experience left Kathy with lingering stroke-like symptoms, including a sudden, transitory inability to understand what people say to her. When they visited the house in which Zeitoun was “arrested,” they discovered that actually looters — most likely including uniformed thugs like the ones who kidnapped him — had stripped the place bare.

While Zeitoun and his friends, along with scores of other perfectly innocent people, were detained on spurious charges, the “forces of order” were running amok in the flood-devastated city.

Dozens of New Orleans’s, ahem, finest fled the city. Those who remained made life considerably worse for the productive people who stayed behind. On September 4, New Orleans police officers gunned down refugees trying to flee the city by way of the Danziger Bridge; they then conspired to cover up that atrocity. Armed parties like the one that kidnapped Zeitoun and his friends invaded homes and confiscated firearms from innocent citizens.

***

***

In his History of the French Revolution, Thomas Carlyle maintained that human society exists atop a roiling mass of lava that can erupt and destroy everything in its path once the brittle crust of civilization is breached. Those breaches are usually the result of state action. Occasionally — as was the case in post-Katrina New Orleans — the state exploits a rupture resulting from a natural catastrophe.

At the slightest excuse those who presume to rule us will treat us exactly as Abdulrahman Zeitoun was treated. Before being kidnapped and imprisoned by the government, Zeitoun never suspected that a potential gulag was lurking inside the local Greyhound station. He sees the world much differently now, as should we all.

Be sure to tune in for Pro Libertate Radio each weeknight from 6:00-7:00 Mountain Time on the Liberty News Radio Network.

Dum spiro, pugno!

Content retrieved from: http://freedominourtime.blogspot.com/2010/03/greyhound-station-gulag.html.