In the present pandemic panic, a great many are calling for bigger, stronger, and more brutal government to deal with the coronavirus. Thus, they cheer as the political decision-makers, never wanting to let a good crisis go to waste, scurry to get themselves ‘emergency powers’.

A common assumption among both common people, the intelligentsia, and members of the political class appears to be that the market either has failed or that it simply cannot deal with problems like pandemics. While both are ignorant and false claims, what is much more disturbing is the fundamental lack of understanding for economic organization that they indicate.

The business world

In any rapid change, businesses struggle to the degree they are ill prepared or lack agility. If you were locked in to produce horse carriages when Henry Ford started mass production of the Model T, or flip phones when Apple launched the first iPhone, you were in trouble. There is, from a business perspective, no difference whatsoever between a sudden shift in what consumers want and a pandemic. Yes, that’s right: there is no difference.

The reason is simple: businesses make money from providing what there is demand for and having produced it at lower cost than the price they can charge. What we’re seeing during this coronavirus panic, with for example alcohol producers shifting to hand sanitizers, is not an unexpected altruistic turn by business that some make it out to be. Yes, many businesses are gifting the goods for now. But the greater point is that the firms exercise good entrepreneurship and business management by adapting to the new situation to produce what there is greater demand for.

What is important here is that they are able to do so by calculating the expected bottom line. Whether or not liquor sales plummet, there is value in shifting some of that production to hand sanitizers. But how much? That depends on what the business can afford (when gifting the products) and what the expected sales is (when not). The fact is that there is money to be made from goods that consumers more urgently demand—be it hand sanitizers or automobiles or smartphones. And businesses are ultimately assessed by their bottom line. If they do not earn profits, they will (eventually) die.

The government world

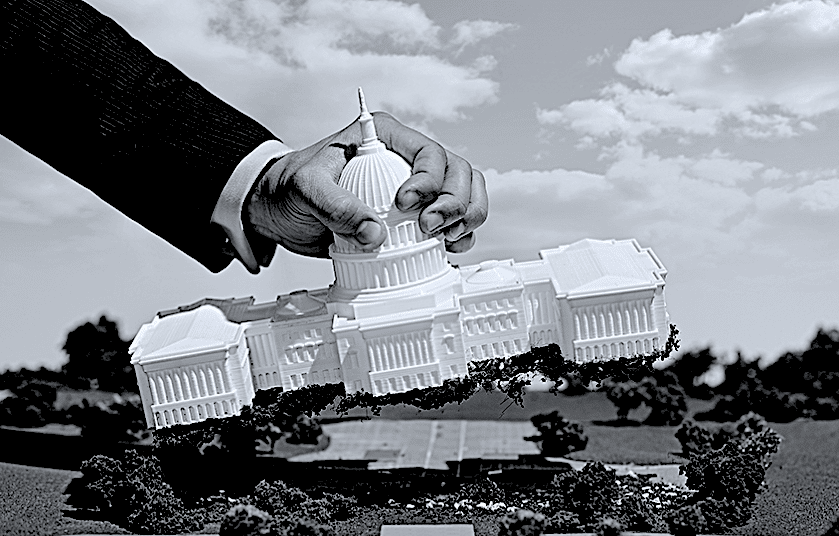

While a CEO of a business is evaluated using a number of measures, the company’s bottom line—its profitability in the present and future—is first among them. But government is altogether different: there is no bottom line and no way of measuring actual performance.

For political leaders, there is only reelection or not. Their chances of remaining in office depend on their perceived track record, which will partly be determined by what issues are raised by competitors’ election campaigns and what is given attention in the media. There is no objective measures of their entire legacy and there is also no one metric that summarizes it. Opponents will point to anything that didn’t (or can be made out to not) end up well as a failure of leadership.

During a crisis situation, therefore, political leadership can be blamed for doing too little but not for doing too much. If they do too little, it is easily pointed out as a failure of leadership. If they do too much, then there is no way of knowing that it was indeed too much—because the only available ‘metric’ is the outcome.

Compare to a CEO of a business firm: doing too little is appropriately recognized as poor leadership and reflected in the bottom line as a lower return than other businesses—and perhaps a loss and perhaps falling market share. If they do too much, they’ve accepted too high cost. The bottom line reflects this fact too, with the firm earning a comparatively low ROI or suffering a loss.

Not so for politics, in which there is no reasonable metric—and also no comparison. In this pandemic, for example, the real cost of adopting ‘emergency’ measures cannot be measured as it is passed on to society overall and borne by everyone in it. The real cost could not be known for many years, if at all, and there is nothing to compare to as government is a monopoly. What can be known is whether the outcome is good or not.

The bottom line

As a result, while business leaders are evaluated by how prudently and effectively they direct the firm, political leaders worry only about doing too little. There is no upper bound to what they might try during a crisis. What limits the scope of what policies might be tried is primarily their personal conviction—their ethics. But they also realize that being ‘too ethical’, meaning ‘not doing enough’, might make their reelection impossible.

It does not matter how good-hearted or prudent political leaders might be, the incentive is always to do more—not to prudently respond to facts of the situation. In a situation of widespread fear, such as this pandemic, political leaders who do not meet people’s emotional demand will face an extremely difficult reelection campaign and they might even be forced to resign.

Politicians are consequently better off to do much more than needed. And they are also better off focusing on such measures that people directly observe or feel, whether or not they are effective. We thus see politicians acting swiftly and forcefully, as is in their interest. It is also what people call for them to do.

The prudent decision-making, a.k.a. good leadership, that we need in crises much more than under normal circumstances, is quickly dismissed. And we will never know exactly how much ends up being destroyed as a result.