Although we’ve been given a brief respite from COVID-19 pandemic news, it’s likely that the killer of over one hundred thousand so far in America will leap back to the front page and that continuous calls to flatten the curve will return to top of the mind.

As a friend and fellow ex-University of Nevada Las Vegas (UNLV) Rothbard student reminded me, flattening the curve essentially means to socialize medicine: to ration healthcare, giving preference to COVID sufferers at the expense of non-COVID emergency medical care and elective procedures.

If the US healthcare system is the cowboy capitalism that many believe it is, why aren’t there doctors, nurses, and PPE (personal protective equipment) in abundance? Why the need to portion out medical care and talent?

The American Medical Association (AMA) was founded in 1847, incorporated in 1897, and as Paul Starr wrote in “The Social Transformation of American Healthcare: The Rise of a Sovereign Profession and the Making of a Vast Industry,” “The key source of physicians’ economic distress in 1900 remained the continuing oversupply of doctors, now made much worse by the increased productivity of physicians as a result…[of the] squeezing of lost time from the professional working day.”

Starr points out that the number of medical schools expanded at the end of the nineteenth century. From the founding of the AMA to 1900, the number of medical schools more than tripled from 52 to 160. The population expanded 138 percent between 1870 and 1910, while the number of physicians increased 153 percent.

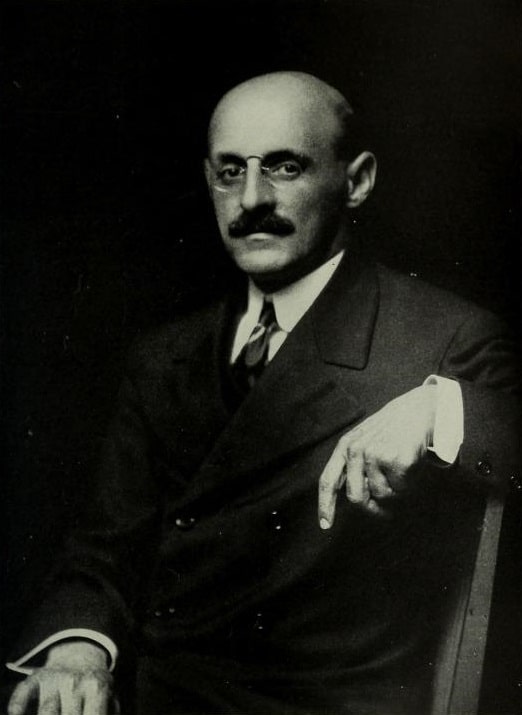

“The weakness of the profession was feeding on itself; ultimately help had to come from outside,” Starr wrote. Help came in the form of the Flexner Report, penned by Abraham Flexner, whose claim to fame was being the brother of the powerful Dr. Simon Flexner, a key player in the chase for a vaccine to battle the 1918–19 Spanish flu,which killed 35 to 100 million people worldwide.

Brother Abraham was not a doctor himself. And while the report was commissioned by the Carnegie Foundation, “Flexner’s report was virtually written in advance by high officials of the American Medical Association, and its advice was quickly taken by every state in the Union,” Murray Rothbard explained in Making Economic Sense.

Using the Flexner Report as a guide, the AMA was able to use the state to cartelize the medical industry. Rothbard wrote,

The result: every medical school and hospital was subjected to licensing by the state, which would turn the power to appoint licensing boards over to the state AMA. The state was supposed to, and did, put out of business all medical schools that were proprietary and profit-making, that admitted blacks and women, and that did not specialize in orthodox, “allopathic” medicine: particularly homeopaths, who were then a substantial part of the medical profession, and a respectable alternative to orthodox allopathy. (Making Economic Sense, p. 76)

The report recommended closing schools, competing therapies, and minority doctors that were considered substandard. “Medicine would never be a respected profession…until it sloughed off its coarse and common elements,” wrote Starr. Medical schools had been closing before 1910, with 20 percent shuttered in the four years before the report was published. Capital requirements for moden laboratories, libraries, and clinical facilities “were what killed so many medical schools in the years after 1906,” Starr wrote.

Rothbard explained further,

In all cases of cartels, the producers are able to replace consumers in their seats of power, and accordingly the medical establishment was now able to put competing therapies (e.g., homeopathy) out of business; to remove disliked competing groups from the supply of physicians (blacks, women, Jews); and to replace proprietary medical schools financed by student fees with university-based schools run by the faculty, and subsidized by foundations and wealthy donors. (Making Economic Sense, p. 77)

A reader can pick up plenty of books on the Progressive Era and find barely a mention of the AMA, yet the medical mess we have today took root during that era. Some of us still remember house calls, five-dollar office visits, worn black medical bags toted by doctors with stethoscopes dangling from their necks. Before the Flexner Report, mechanics made more than doctors and the brightest students avoided the profession to enter the clergy.

The burgeoning cartel meant “a skewing of the entire medical profession away from patient care toward high-tech, high-capital investment in rare and glamorous diseases,” wrote Rothbard, “which rebound far more to the prestige of the hospital and its medical staff than is actually useful for the patient-consumers” (ibid., p. 77).

Abraham Flexner, according to Starr, “had an aristocratic disdain for things commercial.” The high-minded Flexner Report “more successfully legitimated the profession’s interest in limiting the number of medical schools and the supply of physicians than anything the AMA might have put out on its own.”

The result: after peaking at 162 medical schools in 1906, by 1922 the number had been cut in half. The Flexner Report (a.k.a. Bulletin Number Four) recommended that the number of schools be reduced to thirty-one. Fortunately, more than seventy survived. Left up to Flexner, twenty states would not have had a single medical school. Legislators intervened. The report “was the manifesto of a program that by 1936 guided $91 million from Rockefeller’s General Education Board (plus millions more from other foundations) to a select group of medical schools,” according to Starr. Two-thirds of these funds went to only seven schools.

Medicine made a great leap in the Progressive Era. “The transition from household to the market as the dominant institution in the care for the sick,” in addition to increased specialization of labor, “has created emotional distance between the sick and those responsible for their care,” Starr wrote, “and a shift from women to men as the dominant figures in the management of health and illness.”

The true sign of the elevation of doctors in society was evident in 1926, when H.L. Mencken snidely wrote, “Kiwanis, like golf, is a symbol of the business man’s natural desire to break the dreadful monotony of his days. And when I say businessman, I include also, of course, the doctor, the dentist, the lawyer, and all other bored and laborious walking gents of human comedy.”

Thanks to Flexner, the AMA, and state licensing, today’s healthcare cartel is no laughing matter, but deadly serious.

Douglas French is former president of the Mises Institute, author of Early Speculative Bubbles & Increases in the Money Supply, and author of Walk Away: The Rise and Fall of the Home-Ownership Myth. He received his master’s degree in economics from UNLV, studying under both Professor Murray Rothbard and Professor Hans-Hermann Hoppe. This article was originally featured at the Ludwig von Mises Institute and is republished with permission.