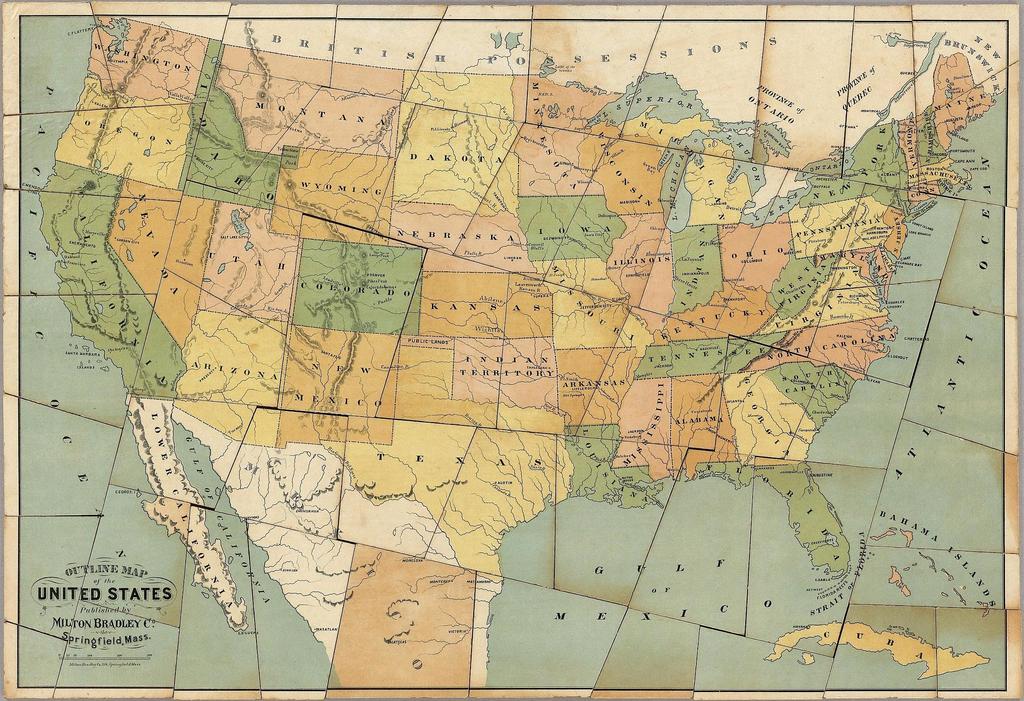

Last week, context was added to Murray Rothbard’s assertion in Wall Street, Banks, and American Foreign Policy that American foreign policy underwent an abrupt shift during the second Cleveland administration (1893-1897). I argued that American foreign policy from that period on, far from being a radical departure from what had come before, was the natural outgrowth or logical extension of previous expansionist policies. In this reading, the drive to conquer the best of the North American continent, having been declared officially settled in 1890, was simply turned abroad in a series of actions, confrontations, and conflicts over Hawaii (1893), Venezuela (1895), Cuba (1898), Samoa (1900), and dozens more.

These apparently sudden, aggressive attempts to seize strategically important overseas territories, install friendly or client regimes, and intimidate rivals can be better understood by examining their antecedents, located in the 1840s and 1850s. For having acquired Louisiana from France (1803), established a northern boundary via treaty with the British (1818), and acquired recognition of claims to the Pacific coast via the treaty with Spain that additionally saw Florida ceded (1819), the years prior to war with Mexico (1846-48) were spent much as the twenty years between the end of the Civil War and onset of the period of imperial expansion of interest to Rothbard were spent: settling and asserting control over newly acquired territories before moving on the next.

This includes the United States many wars against Native Americans in the early to mid-nineteenth century, including the Creek War (1813-14), First and Second Seminole Wars (1817-18 and 1835-42), Arikara War (1823), Winnebago War (1827), Black Hawk War (1832), and the ethnic cleansing of the southeastern United States by forcibly removing approximately sixty thousand Cherokee, Choctaw, and Chickasaw (1830), along with the encouragement and outright fomentation of revolution in the breakaway Mexican territories of Texas (1836) and California (1846).

Apart from eventually initiating the war against Mexico, which participant and later President Ulysses S. Grant referred to in his memoirs as the most “wicked war” ever waged by the United States, attempts to buy Cuba under President James K. Polk (1848) quickly turned to efforts to subvert or invade the island during the Zachary Taylor (1851) and especially Franklin Pierce administrations (1854). The failed filibustering campaigns of Narciso Lopez in Cuba (1851) and later William Walker in Nicaragua (1855), particularly encouraged by southern leaders, were part of a vaster conception of Manifest Destiny, endorsed by its originator John O’Sullivan himself, that envisioned the extension of the United States to Central America and the Caribbean.

Around this time as well the United States government began scurrying around the Pacific and Caribbean gobbling up so-called “Guano Islands,” small rocks covered in hardened mounds of bird droppings rich in saltpeter for use in fertilizer and gunpowder, eventually amassing nearly one hundred of these. It also took part in the Second Opium War (1856) in an effort to secure for itself a share of the China market, as well as force open Japan (1855) for the same reasons.

The similarities to Washington’s behavior in the 1890s and on into the twentieth century being clear, one unsurprisingly finds that the rhetoric was strikingly similar too; such bellicose jingoists as Senators Albert Beveridge and Henry Cabot Lodge, or eventual President Teddy Roosevelt had nothing on the likes of Senator Albert Gallatin Brown, who openly pronounced, “I want Cuba, and I know that sooner or later we must have it…I want Tamaulipas, Potosi, and one or two other [additional] Mexican States; and I want them all for the same reason—for the planting or spreading of slavery.”1Quoted from “An Empire for Slavery,” Sub-Chapter Three of James M. McPherson’s Battle Cry of Freedom.

Likewise, the warmongering of press of William Randolph Hearst didn’t have anything to add to what already existed in the 1850s. “With Cuba and St. Domingo, we could control the productions of the tropics, and, with them, the commerce of the world, and with that, the power of the world,” wrote the Southern Standard; while echoing John O’Sullivan’s many articles on the topic, De Bow’s Review pronounced America’s “Manifest destiny over all Mexico, over South America, over the West Indies.2Ibid

Note: while the push for a vast southern empire built on slavery and raw materials export was powerful and drove many of the foreign policy decisions of the period, northern free labor, mercantile, and protectionist interests won their share of the fights and exerted significant influence. For example, the push to capture market share in East Asia, the enactment of the tariff of 1842, and the taking of a hard line with Great Britain over the size of Oregon was all for the benefit of the northern economy.

Thus contextualized, the Civil War (1861-65) appears as an interruption in this general process of expansion, a period when the competing elites of the North and South conscripted their populations to bloodily vie for control of the manner of future expansionary policies. Rather than becoming a tariff free exporter of raw commodities, whose direction of expansion was largely directed southward, the victory of the North meant the United States became a tariff protected manufacturing hub whose primary imperial policy consisted of securing markets for its goods along with acquiring the necessary basing facilities to protect those trading interests.

Reconstructing the American state and society in the aftermath of the Civil War, or rather allowing things to sort out as they would, occupied much of the 1870s. The Compromise of 1877, when Republicans traded further efforts toward Reconstruction for the White House, marked the end of this process; and, as was seen last week, the imperialist thrust resumed thereafter in the 1880s. There is, therefore, an argument to be made that this resumption of imperialist expansion had a distinctly social dimension to it. The remaining Indian Wars—the Nez Perce War (1877), Bannock War (1878), White River War (1879) and Crow War (1887), as well as the war against Spain (1898)—served as a kind of glue, helping Washington suture North and South back together in the face of intense social, political, and economic upheavals.

For all the mythologizing to the contrary, American foreign policy has always been demonstrably aggressive. The acquisitive tendency in human nature and the missionary and commercial foundations of the United States aside, the very nature of the state and the competitive logic of the international system tend toward conflict. The state is, as Rothbard wrote, the organized means of coercively extracting resources; so long as it exists, there will always be those who seek to further their own interests by instrumentalizing state power, socializing the costs of achieving their own desired ends. While this will generally be done under the guise of national greatness, national security, or some other such pretense, such familiar paths have been the roads to ruin of every republic come down through the annals of history.

While limitations of space prevent detailed descriptions of each of the above events, it is worth noting that for all its sense of seeming invariability—even inevitability—the expansionists often barely carried the day.

It could have been otherwise.

And so although today the deck seems equally stacked against those inheritors of the long and great anti-Imperialist tradition in America, they should take heart.

For it, too, can be otherwise.