There was a time when one would have to wait for a theatrically released movie to appear on television before it could be seen again. Only certain movies would be available and then often edited for run time and censorship concerns. Then came the video tape and movie rentals. Suddenly all sorts of titles, even those not originally shown at the cinema, were available on home video. And inevitably, government stepped in to prohibit and regulate which videos a person was allowed to view.

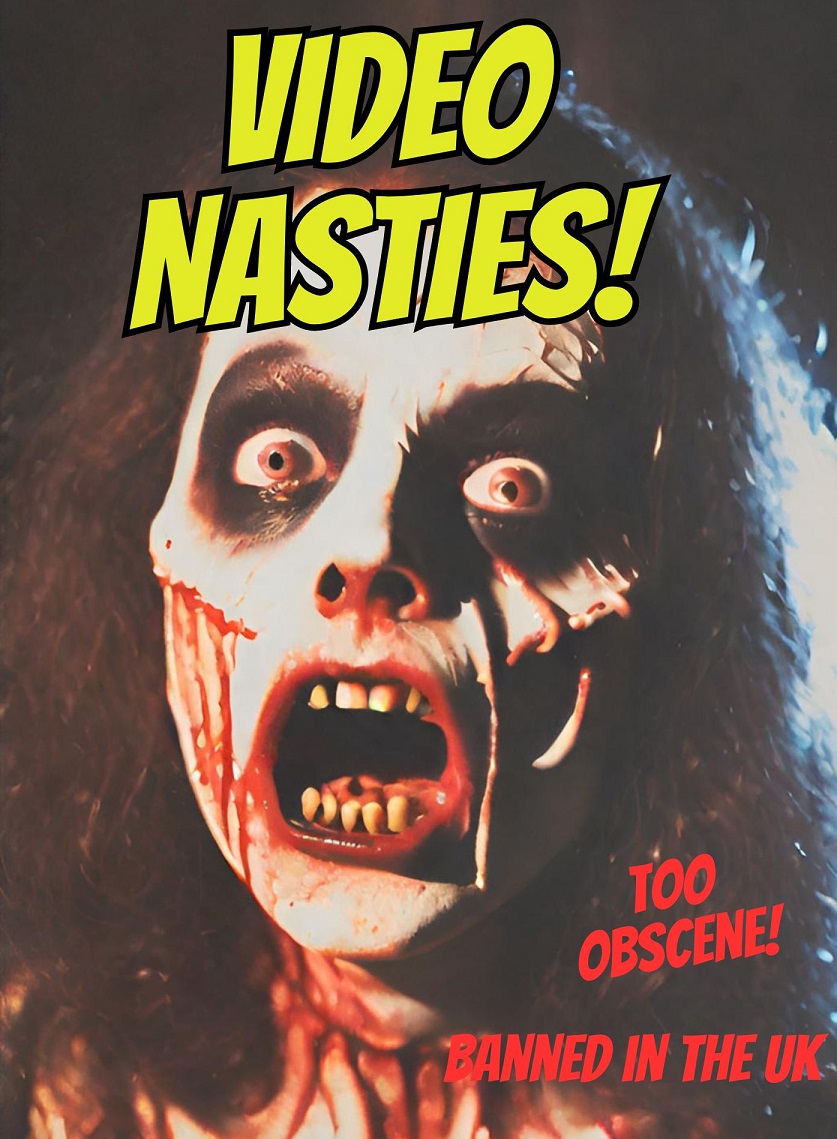

In Great Britain a panic emerged: it was known as the “Video Nasties,” and the Conservatives and religious moralists ran a crusade against films which they deemed “obscene” or “too nasty” for the British household. As always, the concern was for the children. “What would happen if a child was to watch such a film?” Spoiler alert; we grew up to be awesome.

The term video nasty came about as a general media friendly term used by the National Viewers’ and Listeners Association to describe obscene cinema. Most of the films defined as such were usually low budget, independent horror movies that pushed boundaries and in some instances became influential pieces of art.

Many of the banned films were those that depicted acts of graphic violence or that delved into paranormal themes. Pornography, as always, was targeted as well, although the main focus was on the exploitation era films that defined 1970s and early 80s cinema. Cannibal Holocaust was one of the earlier films that was singled out to be banned. The creators of Cannibal Holocaust, in an attempt to stir up controversial interest in their film, would write letters of complaint to notable conservative and religious heads in the hopes that any press was good press. The response was far more adverse to their film than they could have anticipated, helping to get it banned instead. Too deplorable for British eyes, you understand.

Sam Raimi’s The Evil Dead also made the list, the title alone presenting frightful words for the censors to experience. Texas Chainsaw Massacre was also a video nasty, not so much because what it showed but what the viewer was left to imagine. Director Tobi Hooper left most of the violence off screen, allowing the mind to fill in the blanks. A film that made the list based entirely on its title was the Dolly Parton and Burt Reynolds musical comedy, The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas. Like other films on the list, it’s unlikely it was watched by the outrage mob or any of the bureaucrats implementing the law. Though oftentimes, confiscating police officers would hold pizza and viewing parties where they could view such deplorable cinema. At least someone in the UK was allowed to enjoy them.

Leading the charge and lighting many of the panic torches was social moralist Mary Whitehouse. For American readers, imagine Tipper Gore on steroids blended with Dana Carvey’s “little churchlady.” Whitehouse pushed for regulation and censorship; she wanted the British Board of Film Censors to be a muscular and active body that could influence art and what the in-the-privacy-of-their-own-home audience was allowed to watch. The BBFC became a gate keeper and destroyer of free expression to cinema in the United Kingdom.

The muscles were bulging with moral panic to the point where the director of Cannibal Holocaust was charged with murder. The actors in the film had to turn up as witnesses to prove that they were in fact acting and not killed in the accused snuff film. The Department of Public Prosecutions invented the official video nasty list, which at its peak had around seventy plus titles on it (that number varies). Films would fluctuate on and off the list, with police and distributors uncertain as to what films were actually on it. The list had a tendency of varying from county to county, making it hard to anyone to know what was forbidden and was allowed by the Crown. Arbitrary law enforcement from local officers was in effect. Raiding police officers were known to confiscate a video based on its box art rather than it actually being officially banned at all. Since the criteria for what was to be banned waned and was ill defined, final judgement fell on what was felt by those doing the banning.

Apocalypse Now was briefly banned on the assumption it was a horror film, and Sam Fuller’s war film The Big Red One was prohibited because the title was seemingly too sexy. One could only assume what Lee Marvin and Mark Hamill were doing with a “Big Red One!” Most police officers confiscating and imposing the law knew little about cinema. The punishment in the most severe cases was a twenty thousand pound fine and/or up to three years in prison. The Video Act of 1984 made certain titles illegal to be in British video shops. Films such as Dario Argento’s Tenebrae (1982) remained banned until 1999.

When a video distributor was charged, filmmakers were not called into court to testify. The process was heavily slated in favor of the prosecutors. With no real consistency, fear and moral bias steered the judgement, with media peddling lies that the banned videos were “raping” the minds of the youth and were responsible for murder, suicide, and acts of sexual violence. The cancel culture of the moralists had the full weight of the British government behind it. A new media had emerged that frightened the controlling powers and social commentators of their time.

Along with Mary Whitehouse, a prominent British religious figure weighed in on the scare. Lord Cogan added a spiritual element to the anti-video crusade. Not only did he claim such videos may be imitated by the viewer, but they were also subversive and damaging to the fabric of British moral society. By 1985, the list of banned films was down to thirty-nine, though it had influenced how films were “cut” for British audiences, while also having an impact on television and locally made movies in the United Kingdom. Famously, The Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles had to be re-titled to Teenage Mutant Hero Turtles, such was the idiotic need to police media.

Busy body moralists found the perfect prime minister in Margaret Thatcher, who embraced certain conservative sensibilities and, for all the celebrated pretenses of her being a champion of freedom, she was an active leader when it came to such censorship. The anti-communist PM shared a common moral concern when it came to censorship as to what her comrades on the other side of the Iron Curtain held.

The video nasty frenzy would not have been possible, or at least not so prominent, without Thatcher at the helm of the nation. Similarly, the Satanic panic and its concerns over Dungeons and Dragons, heavy metal, and (as always) pornography in the United States wouldn’t have reached a fever pitch without Ronald Reagan. The past decade has seen a right-wing white washing of history where the cancel culture and censorship obsession has been solely attributed to the political left, when in reality it’s most often come from conservatives.

During the height of the 1980s video nasty era, older films that were once accepted as watchable cinema suddenly became illegal and banned titles. The rationale was that children had access to these video tapes. This was determined by asking school children if they had watched movies that were in the naughty banned list. Free speech advocates emulated the survey, instead using fabricated movie titles and had similar results. It turns out that young children can often say whatever, and cool sounding film names may appear exciting to some youngsters, whether they had seen them or not.

The consideration that adults may also enjoy movies of a mature nature was never really a factor by the parent government. Just as video games, animation, and comic books are assumed by busy body statists to be a child-only medium, the rights of mature minded viewers/readers/players are not considered. To quote Helen Lovejoy, “Won’t somebody think of the children!” Since video nasties could allegedly pervert and damage a child’s mind, a nation that considered itself free would set out to ban them all.

The word “freedom” is thrown around often, and is used to justify a great many things, including war. But how we define this term seems to vary. Usually democracy, or at the very least the process of democratic governance, is conflated with the word freedom. When advocates of a certain type of morality spin their deception and fears, the mob will accept a great many things. The police and public service will administrate and enforce any law. It’s their job; they are paid to do so.

Video nasties are one of the many periods of irrational fright expressed by the most unimaginative segment of a population. Sex and violence will always hold a fascination as long as they remain taboo. Government will always be infected by those who wish to use its monopoly on violence to satisfy insecurities and sensibilities. The freedom to choose is sacred; it allows us to either not watch a video or put it in the VCR for own viewing pleasure (or discomfort). The irony is that physical media is slowly coming back into vogue because of digital censorship. The videos on the nasty list are ever popular and sought after. Sometimes freedom is Ash chainsawing a deadite in half, or watching Lee Marvin storm the beaches of North Africa with an M1 Garand in hand. Then again, someday Dolly Parton singing on screen may again be too obscene, for two distinctly large reasons. Rest assured, when that time comes the screaming SJWs won’t be doing the censoring. It’ll be your friends on the right.