To understand how American citizens today can get their hands on ammo, which rolls off the same factory lines as those that supply the world’s largest militaries, it’s important to first understand how munitions technology developed. Starting in medieval Europe, on a battlefield where a mounted knight in armor could defeat almost any number of peasants, the development of more advanced and accurate ways to destroy enemy personnel and equipment by launching a projectile is one which combines trial and error, scientific ingenuity, and private enterprise. It’s a story of power and technology dating back to the 13th century, at the height of “the divine right of kings,” and tracks the subsequent diffusion of that power held by a chosen few as the individual became capable of breaking the state’s monopoly on violence.

The first recorded use of gunpowder appeared in Europe in 1247, although China had used gunpowder for centuries before that, mostly for fireworks. The cannon appeared nearly 100 years later in 1327, with a hand-sized version making its debut in 1364. The first ordnances were made of stone, and while it might have been theoretically possible for anyone to own one, this would have been outside the financial reach of anyone but the nobility.

Stone was quickly discarded as a source of materiel for one simple reason: It wasn’t effective against stone fortifications. Thus did the first ever arms race begin, as medieval armies sought ways to fire heavier and heavier projectiles. The first recorded example of a metal ball being fired from a hand cannon came in 1425, with the invention of the hand culverin and matchlock arquebus, which led to lead balls becoming the gold standard for projectiles. This is where we get the term “bullet” – boulette is French for “little ball.”

Ammunition remained largely the same for centuries: Little balls of metal virtually anyone could make. This was true until the invention of rifling in the mid-19th century. Even this invention was, at first, not terribly useful for military purposes. Not only did the barrels quickly become useless, but the barrels often could not be fitted with a bayonet. This made early rifles impractical for military use and mostly a bit of a toy. Not until the advent of progressive rifling (which came, depending on one’s point of view, fortuitously or not, in the middle of the U.S. Civil War), did rifles become practical for military, and also widespread civilian purposes.

Copper jacketed bullets arrived in 1882, but since then the development of both military and commercial ammo has largely been about degrees rather than revolutionary innovations like rifling. The same basic design for cartridges has been in place since the late 19th Century.

Advancing technology was likely a driver in the move toward ammunition produced for commercial purposes, rather than simply military use. While in the past, it was common to simply make lead balls in front of the fire as a family after dinner, making a modern rifle cartridge is far beyond the means of most people. Further, it requires safety procedures above and beyond simply molding lead balls.

What Is the Difference Between Civilian and Military Ammunition?

For the most part, the distinction between civilian and military ammunition is largely down to marketing. However, there are some important differences between civilian and military (often known as “milspec”) including:

Treaty Restrictions

All military ammunition is full metal jacket. There are military treaties requiring this on an international scale, beginning with the Hague Convention in 1899. Civilian ammo is not subject to such requirements and can be full metal jacket, composite, hollow point or any other configuration.

As a rule, civilian ammunition is designed to expand upon impact. Military ammo is not, due to treaty restrictions. Military ammunition frequently passes through a target with no serious damage, whereas civilian rounds are designed for “one shot, one kill.” This is not a purely humanitarian consideration: Wounded soldiers are a greater burden for an army than dead ones.

Climate Protection

Military ammunition comes with moisture sealant, while civilian ammunition does not. This is due to the wide array of climates that military ammunition might be used, as well as the fact that military ammunition might be stored for decades before it is actually used.

Primers

Military ammunition primers are harder than its civilian counterparts. This helps to prevent accidental discharges, the worst case scenario of which is when a weapon gets stuck in automatic fire mode.

Chamber Pressures

The chamber pressures are different between military and commercial ammunition, though the degree to which they are different varies significantly from one caliber to another. As an example, the 7.62x51mm NATO and the .308 Winchester are basically the same round, but the NATO (military) version has lower pressure.

Sometimes the military version of a round can be fired through a weapon chambered for the civilian version and vice versa – but sometimes the compatibility only works one way. For example, the military weapon can fire the civilian round, but the civilian weapon cannot fire the military round. Never assume that a military and civilian round and chamber are cross-compatible.

Consistency

Civilian ammunition tends to be far more consistent in terms of its dimensions than military ammunition. Because every round simply must feed and fire properly, military ammo allows for looser tolerances than civilian ammunition.

Casings

Military ammunition casings tend to have thicker walls because, as a general rule, they are subject to higher pressures than civilian rounds.

It’s common for civilians to buy military ammunition, either because they want the particular qualities of that cartridge or because they simply want to get a deal on price. For the most part, there’s no problem with buying surplus ammo provided that your weapon can handle it. You should also examine the ammunition when you receive it — as stated above, it’s not uncommon for rounds to sit in storage for decades.

The Springfield Armory and Commercial Ammunition

The use of the location for military training dates back to the colonial days, when George Washington personally scouted and approved of the site during the Revolutionary War. The entire city of Springfield was built around the armory, which wasn’t much to speak of at the time: Little more than an intersection of rivers and roads. These features, however, are what made the location optimal for the manufacture of weaponry for the war effort. What’s more, the Connecticut River provided a natural defense against naval attack.

Shays Rebellion attacked the Armory, but was unsuccessful, as the state militia was able to defend it from attack using grapeshot. The Armory started producing ordnance in 1793, which included everything from paper cartridges and musket balls all the way up to howitzers. Flash forward to the post-Civil War period, and for a brief time this was the only federal armory in operation after the destruction of Harpers Ferry. It produced the first firearm native to America, the Model 1795, a .69 caliber flintlock musket.

The Springfield Armory was a huge driver of the Industrial Revolution in the United States. This was part of the United States military’s need for replaceable parts on the battlefield under the theory that it was easier to replace parts than it was to repair weapons on the battlefield. In turn, this made it easier for the average person to own and maintain a firearm. No longer did one have to know anything about gunsmithing or pay a gunsmith to keep a weapon in good working order. Now one could simply replace parts as they broke down.

Commercial Ammunition in America: The Big Four

For clues to where the story of commercial ammunition comes from, it’s worth looking at the history of America’s oldest weapons and ammunition manufacturers: Remington, Smith & Wesson, Colt and Winchester. These are four American brands as iconic as Coca-Cola, Levi’s, McDonald’s or General Motors. And they all play a role in the transformation of the arms industry from a martial enterprise into a commercial one.

Remington

Remington Arms is the oldest gunmaker and operates the oldest factory still making firearms and ammunition to this day. It is also the largest domestic producer of rifles and shotguns. Remington is responsible for the development of more cartridges than any other ammunition manufacturer in the world. As such, they are not just an early adopter in the world of commercial ammunition manufacturing and sales – they are also a world titan of commerce.

The transformation of Elijah Remington from a shooting enthusiast into a gunsmith gives us a bit of insight into commercial ammunition development. He designed his own flintlock rifle for a shooting competition. He didn’t win, but observers were so astonished with his custom-made weapon that offers started pouring in.

Weapons like the Remington Model 1858 were a big part of what won the West. Buffalo Bill Cody carried a modified version of this weapon, in the form of a New Model Army .44 with an ivory handle – which sold for $239,000 at auction in June 2012. Likewise, the Remington Rolling Block rifle helped to clear the West of buffalo, and it’s estimated that more of the American bison fell to this weapon than any other, along with the Sharps rifle.

Colt

The next big name to appear on the scene was Samuel Colt. While his company did not incorporate until 1855, his game-changing percussion revolver, the Colt Paterson, hit the markets in 1836. This was the first revolver and Colt held a monopoly on the production of revolvers through his patent until 20 years later. Unlike earlier weapons designed by Springfield specifically for the purpose of the military, Colt designed his weapon and then later, in an act of shrewd business, was able to sell his design to the United States military. While the innovative design was able to give troops some firepower advantage, the weapons were also notoriously unreliable in combat and were more suited for civilian purposes.

Colt’s New Model Revolving rifle, an attempt to port revolver technology to the rifle, was likewise a hit on the civilian market. It was the preferred weapon of armed guards on the Pony Express, particularly those guarding the extremely dangerous stretch between Independence, MO, and Santa Fe, NM. This particular leg never lost any mail.

Smith & Wesson

Smith & Wesson first began tinkering around with weaponry in 1852. The fruit of their labor was the Volcanic rifle. They were also the first company of note to develop a revolver after Samuel Colt’s patent expired in 1857.

The Civil War represents a turning point in the history of American commercial ammo. Many of the pistols carried by enlisted men, and officers alike, were purchased privately. What’s more, in middle of the war, modern rifling was invented, meaning that weapons became far more accurate, useful and deadly. Handloading became a far more niche hobby – and in any event, the innovation was mostly coming out of the Big Four. Though, it was also the post-Civil War period which saw the rise of wildcatting, where amateur gunsmiths and handloaders were finding ways to improve the commercial offerings on the market.

The post-Civil War period also saw both the United States military and civilian communities turning toward the final conquest of the Old West from the native population. While the impact of the United States Army on this cannot be overstated, it was armed American civilians who settled the West, and demand for weapons and ammunition was high.

Winchester

It was also the period after the end of the Civil War that saw the entry of the final of the Big Four onto the scene: Winchester. The pre-history of Winchester lies in the first company incorporated by Horace Smith and Daniel Wesson, not to be confused with the famous company bearing their name to this day. Their original company was responsible for the Volcanic rifle, the world’s first repeating rifle. Known as Volcanic Repeating Arms Company, it was largely funded by Oliver Winchester. The pair left the company and it was reorganized as New Haven Arms Company, and then as Winchester Repeating Arms Company. While Winchester was the last entrant on the market, they quickly made up for lost time by debuting the Winchester rifle, which quickly earned the sobriquet “The Gun That Won the West.”

While the Winchester rifle saw action in the United States military during the series of conquests known collectively as the Indian Wars, it was an enormously popular civilian weapon, with a whopping 720,000 sold and built. The original Winchester rifle, the Model 1866 (nicknamed “the Yellow Boy”) saw high demand all the way to the end of the century, due to their low cost. The weapon continues production to this day and is approximately as synonymous with the Old West as a Stetson.

Its successor, the Model 1873, was the first Winchester rifle chambered for the 44-40. If the Winchester rifle was the Gun That Won the West, this was certainly the “Cartridge That Won the West.” The primary market for this round was not the military, but lawmen, settlers, and cowboys for the simple reason that it could be used in both a rifle and a pistol. This eliminated the need to carry two different types of ammunition at all times and was a genius stroke of both engineering and marketing on the part of Winchester. Their competitors quickly scrambled to release their own weapons chambered for this enormously popular round. The 44-40 is, among other things, known for killing more deer than any other cartridge.

The Decline of Commercial Ammunition Manufacturing in America

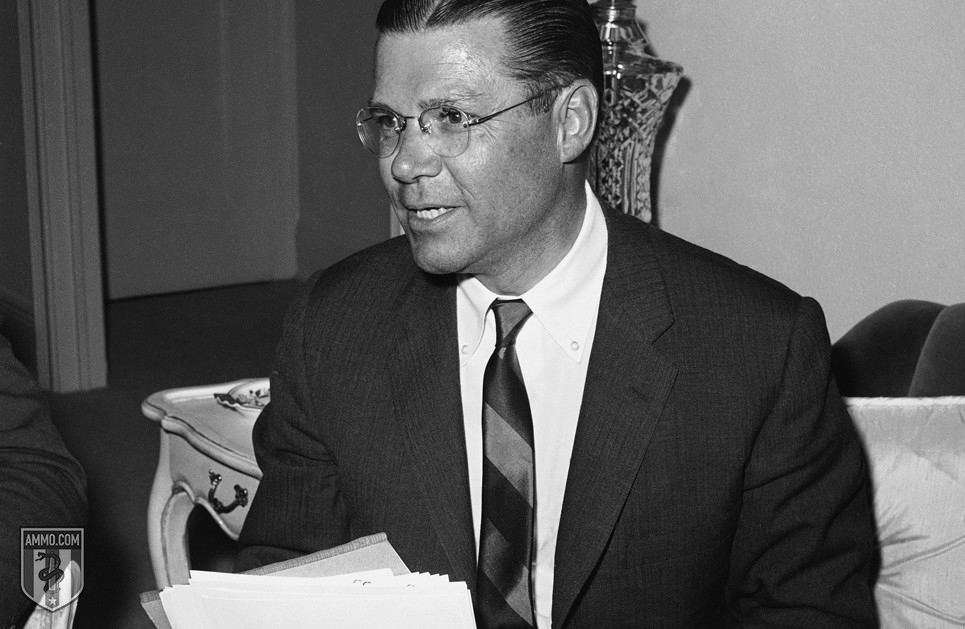

Somewhat ironically, the Springfield Armory was one of the first to go. U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara announced to the public that the plant would close in 1968, because it was in his view “excess to the needs of the federal government,” believing that private arms suppliers would be more efficient.

Many of the outer parts of the Armory were sold off. The core of the campus became property of the City of Springfield and the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, and the site is now a party of the National Park Service, known as Springfield Armory National Historic Site. Several former buildings of the campus are now home to the Springfield Technical Community College. The main building is the home of the Springfield Armory Museum, which houses the Benton Small Arms Collection.

Colt has a slightly different story. It ceased production entirely between 1945 and 1947, with several big retirements occuring at the end of the Second World War. However, the Springfield Armory’s destruction was a boon for Colt, as Secretary McNamara moved a lot of the business from the Armory over to Colt – which finally started seeing its profits fall after the budget cuts at the end of the Cold War.

It all began with a five-year strike. The Colt factory employees were organized by the United Auto Workers, one of the longest-lasting strikes in American history. Replacement workers took the line and there was a noticeable decline in the quality of arms, which negatively impacted the brand’s reputation. By the end of the strike, Colt was sold to a group of investors, the State of Connecticut, and the United Auto Workers. By 1992, the company declared bankruptcy. A boycott, organized in response to CEO Ron Stewart’s statements to the Washington Post that he would favor a federal permit system, didn’t help matters. In 2002, the company spun off its military, defense, and law enforcement wing entirely as Colt Defense. The company reunited in 2013, but declared bankruptcy again in 2015.

Winchester’s decline came in the late 1960s, largely due to a unionized workforce and the increased labor costs that come along with it. A number of hand-tooled weapons were discontinued because the company could not compete with the cast-and-stamped Remington competitors. Much of their product line had been replaced in 1963 and 1964. And for the commercial market, it was no longer seen as a prestige brand, but rather another company selling discount firearms for the mass market. Winchesters made after 1964 continue to be less valuable and less sought after than their earlier counterparts.

A labor dispute proved to be the beginning of the end for Winchester. The strike took place between 1979 and 1980, and ended with the company being sold to the employees as the U.S. Repeating Arms Company. It went bankrupt in 1989, and is now owned by Belgian firm Fabrique Nationale de Herstal. The New Haven plant closed in 2006. Winchester is now an ammunition brand owned by Olin Corporation. It does not produce its wares in Connecticut.

Smith & Wesson fared the best, perhaps, after being sold to American conglomerate Bangor Punta, who diversified the company’s products to include gun-related products such as holsters, as well as breathalyzers and handcuffs for law enforcement. The War on Drugs served to break the back of the company, as law enforcement agencies adopted Glock, Sig Sauer and Beretta. Between the years 1982 and 1986, Smith & Wesson profits fell by a whopping 41 percent, with ownership changing twice during the decade. A boycott organized in response to “smart guns” development nearly destroyed the company. Its current marketing is extremely commercial focused, with the main target being customers at big box stores.

Remington was able to weather the storm a little better than its competitors, in no small part because it was acquired by the DuPont Corporation during the Great Depression. The manufacturing was moved from Connecticut to Arkansas, and from New York to Alabama. Nevertheless, the company took on hundreds of millions of dollars in debt and suffered from an increasingly diminished reputation among the commercial market.

The commercial ammunition market is now bigger than it’s ever been. Popular and common rounds can be purchased at just about any big box retailer in a state with a high degree of gun freedom. Smaller mom and pops have a smaller selection, but if what you need is common enough, you can get it there. Online retailers like us cater to virtually every ammunition need, from the common to the incredibly niche and obscure. And whatever the commercial market doesn’t cater to, handloaders and wildcatters can make.

It’s important to note that when reading the history of commercial ammunition manufacture in the United States and abroad, the commercial market takes a definite backseat to the military. Indeed, the downturns in military spending are a key factor in the downturn of American ammunition manufacturing in general. As unfortunate as it is to read, it’s simply the honest truth that the needs of the military shape the needs of the overall ammunition market in the 20th and 21st Century.

“Commercial Ammo: The Untold History of Springfield Armory and America’s Munitions Factories” originally appeared in the Resistance Library on Ammo.com.