In 1989, the economist John Williamson introduced the phrase “Washington Consensus” to the politico-economic lexicon. It was shorthand for a set of interrelated policies that, taken together, would free trade within states and between them while boosting overall economic outcomes by freeing the productive forces of society from the stultifying effects of statist managerial policies. These were, in no particular order:

- Fiscal discipline, in the form of balanced budgets.

- Tax reform, in favor of lower marginal tax rates.

- Abandonment of fixed exchange rates in favor of competitive, market-determined, interest rates.

- Trade liberalization, including foreign direct investment.

- Privatization.

- Deregulation.

- Ensuring the legal securing property rights.

- Elimination of subsidies.

Born of the economic tribulations of Latin America during the crisis decade of the 1980s, and characterized by high levels of external debt, inflation, and low or non-existent growth, these prescriptions quickly spread beyond their initially intended patients. Applied variously in states across Latin America, Africa, and Southeast Asia, these policies, sometimes derisively referred to by detractors as “neoliberalism,” coincided with a period of unprecedented poverty reduction and growth in the global middle class. Examining the short-hand pejorative “neoliberal,” according to the terms of its detractors, is instructive. As unrelenting critic David Harvey writes, “The neoliberal project is to disembed capital from…State decisions…bound to be politically biased depending upon the strength of the interest groups involved.”

It is hardly surprising, then, that so-called neoliberalism—including free trade—has come under fire in recent years. There are, after all, many groups to whom such goals are inimical to their economic or political interests: domestic manufacturers, organized labor, technocrats, farmers, bureaucrats, and politicians, to name just a few. All of them have various reasons to resist the removal of the state from the economy. From rent collection to campaign contributions, protection from foreign competition and the prolongation of their own time in a position of power, the problem of “concentrated benefits” and “diffuse costs” has long been recognized. What has been surprising, however, given its unquestionable success in raising the collective living standards of the globe, is the relatively lackluster public defense this collection of policies has received in recent years. This essay is, then, for lack of a better word, a paean, or perhaps a dirge, to the so-called “Washington Consensus.”

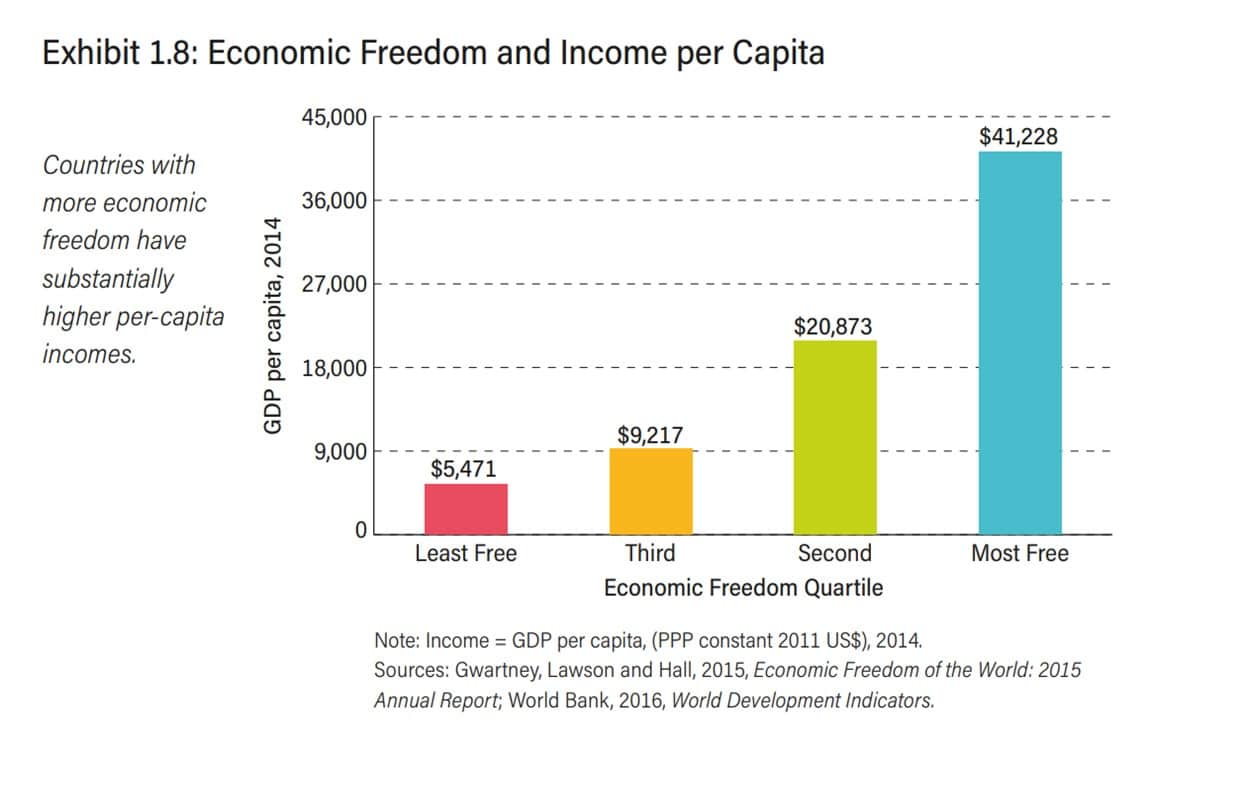

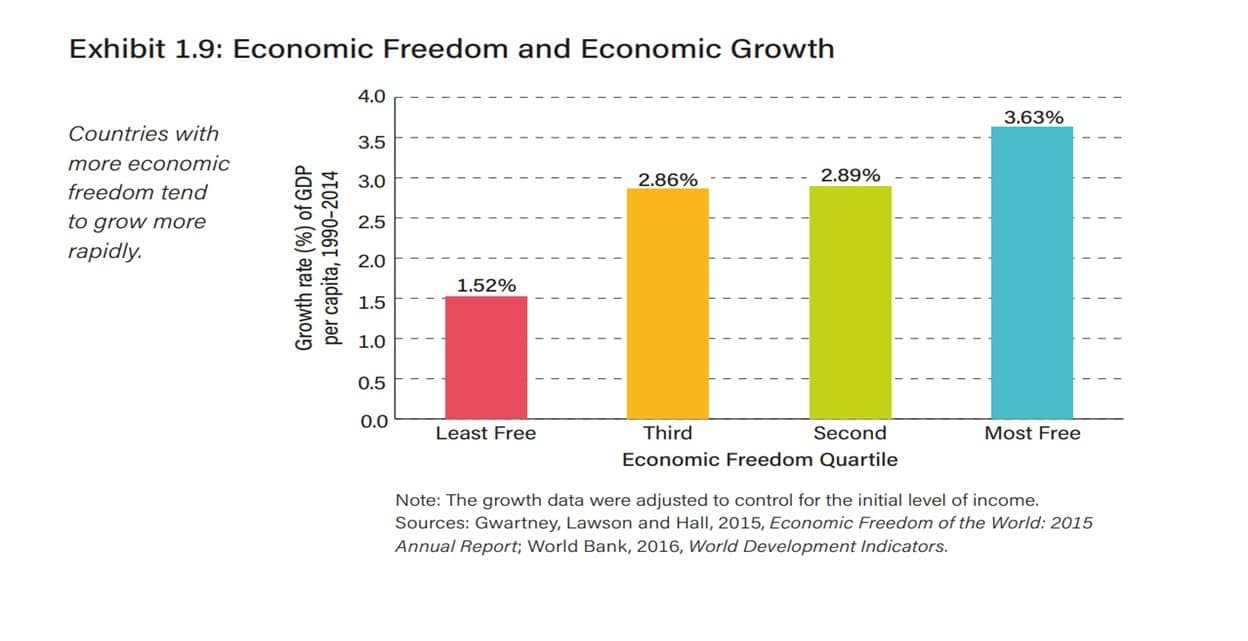

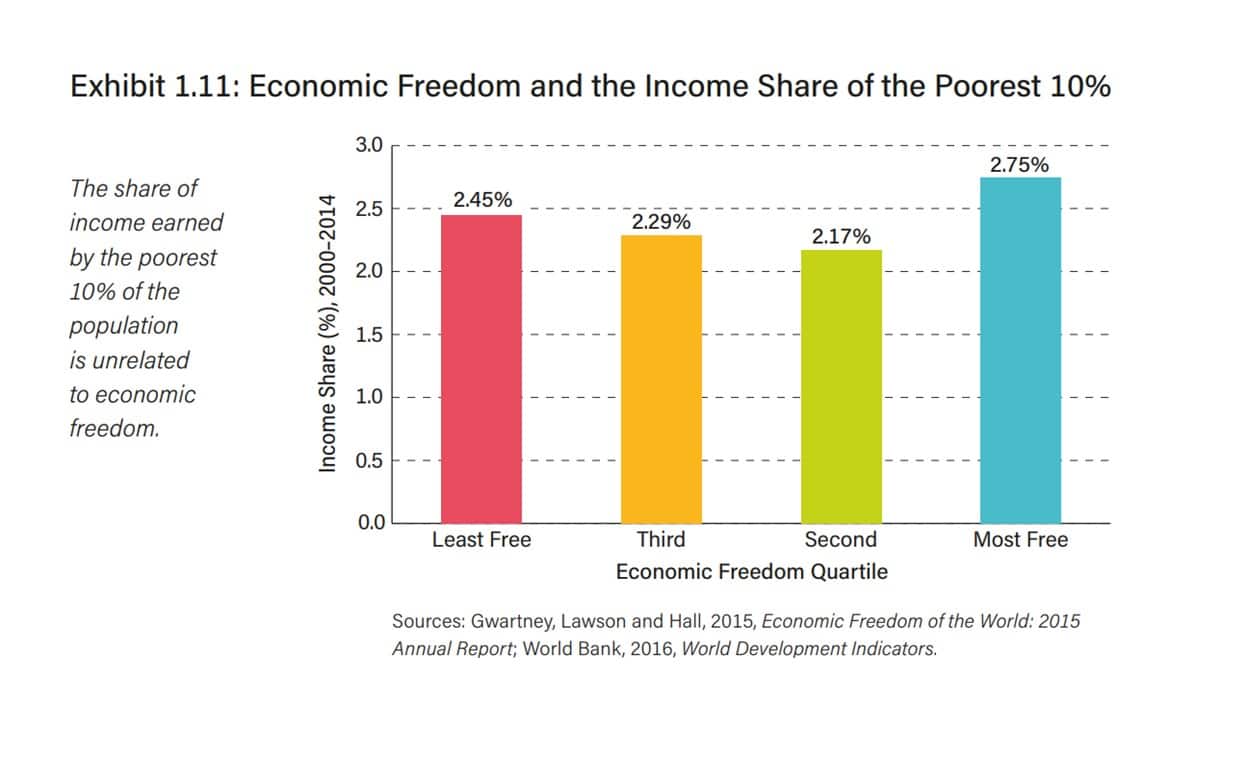

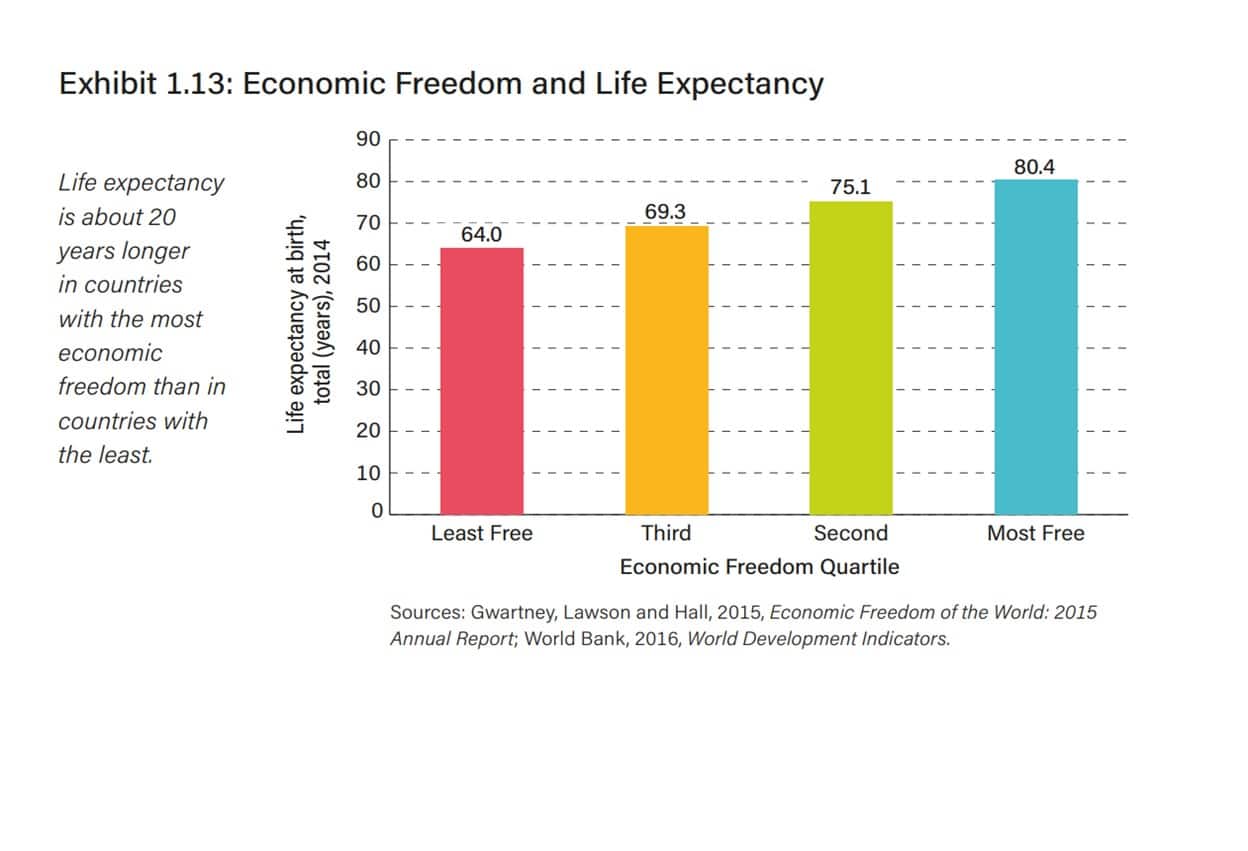

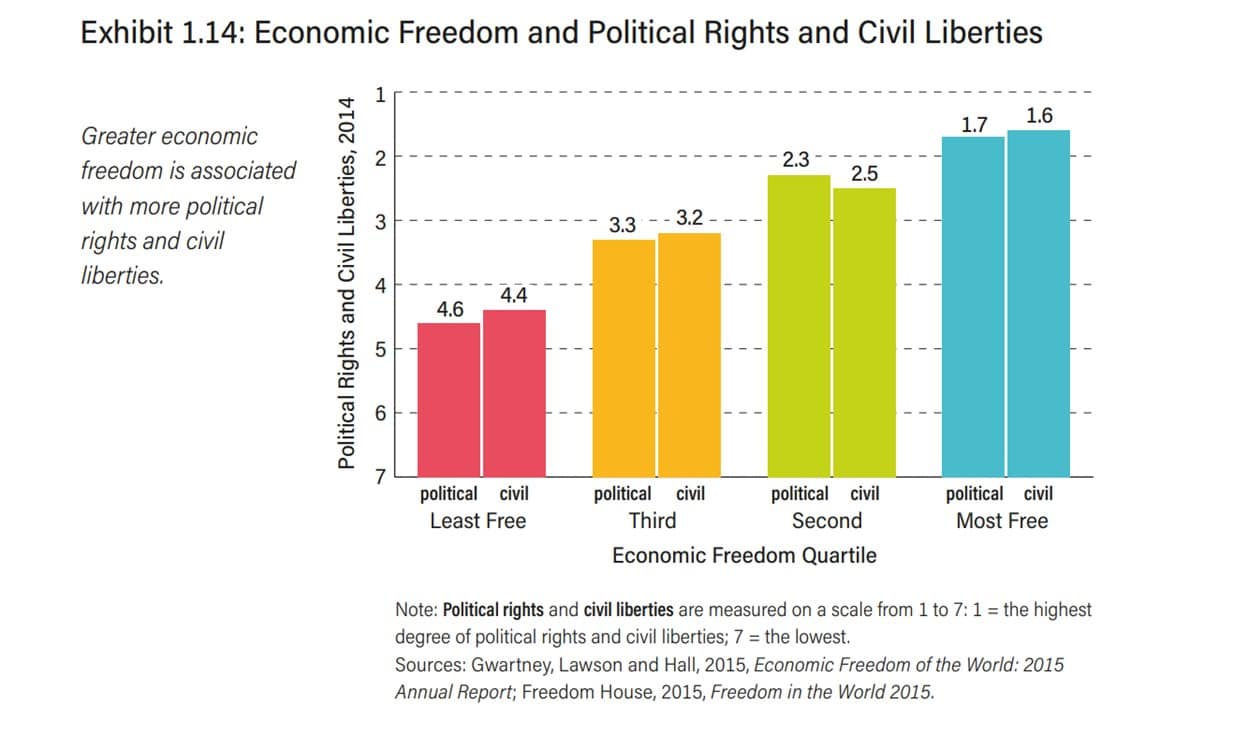

Despite what its detractors say, the truth is that global openness and economic freedom specifically are the key to alleviating problems such as global poverty, economic growth, income inequality, disparities in life expectancy, political rights, and civil liberties (see Ex. 1.8, 1.9, 1.11, 1.13, and 1.14).

Apart from these considerations, themselves by no means trivial, it is estimated that $2 trillion of additional production each year is lost globally as a result of tariffs, subsidies, and import quotas. Further, though it is generally ignored by the media and political class, gains from globalization were critical to the moderation of inflation in the already developed economies of the United States and Europe during the 1990s and 2000s. This, in turn, allowed central banks of the developed market economies, such as the Federal Reserve, to keep interest rates artificially low. Big investments were encouraged in risky technology sectors, which in a higher-cost, higher-interest rate environment might not have been made. These depressed interest rates further could have enabled the government to revamp its infrastructure at a steep discount (that Washington instead chose to spend trillions blowing up the Middle East does nothing to detract from the reality of this globalization-borne possibility as a counterfactual). Even the much maligned North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), prior to Donald Trump’s renegotiation, boosted annual U.S. GDP by fully half a percent, created nearly two-hundred thousand better paying jobs than the estimated fifteen thousand per year that had been outsourced, increased productivity, lowered costs, and boosted U.S. competitiveness.

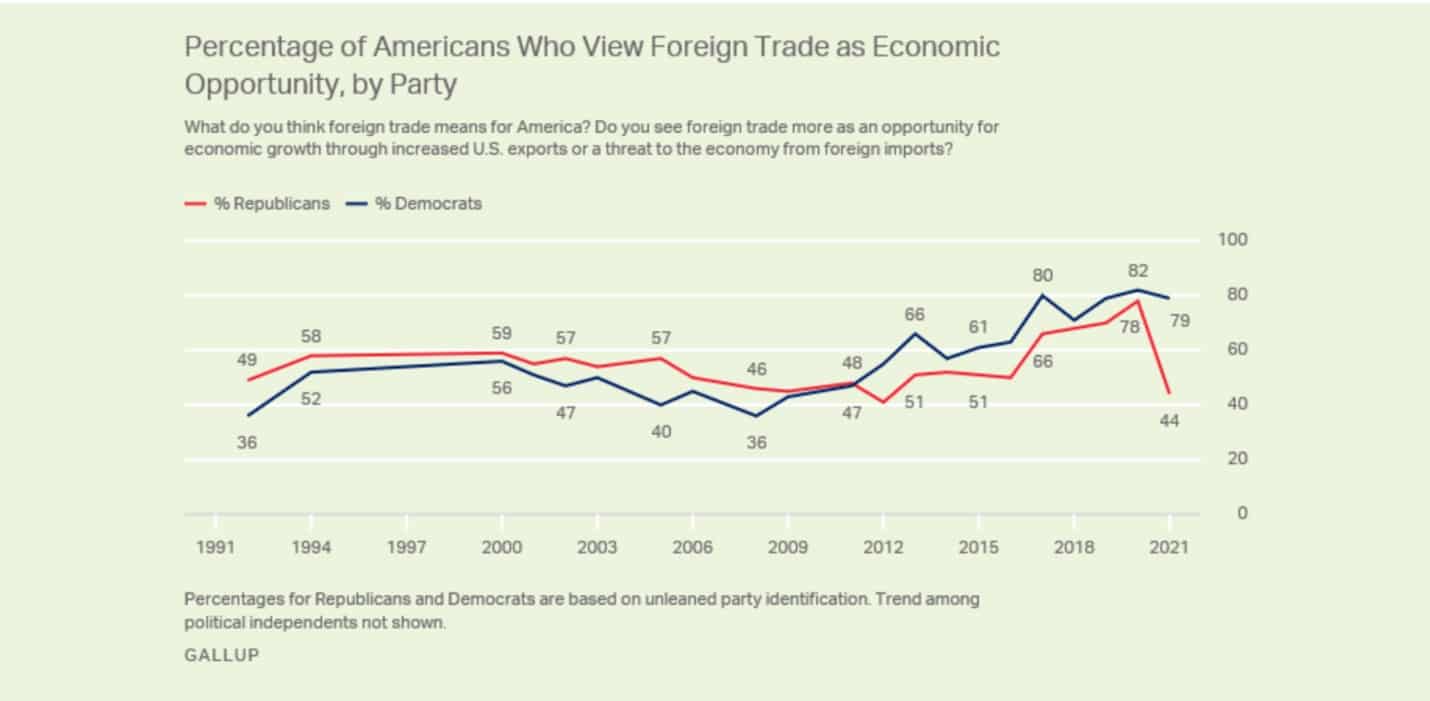

Despite these well-documented facts, there was perhaps no more telling a moment vis a vis the standing of global economic openness than Hilary Clinton’s abandonment during the 2016 U.S. presidential campaign of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), a free trade deal she helped conceptualize and negotiate as Secretary of State under President Barack Obama. This reversal was spurred almost entirely by Trump’s categorical opposition to the deal, Americans broadly having long been supportive of increased trade:

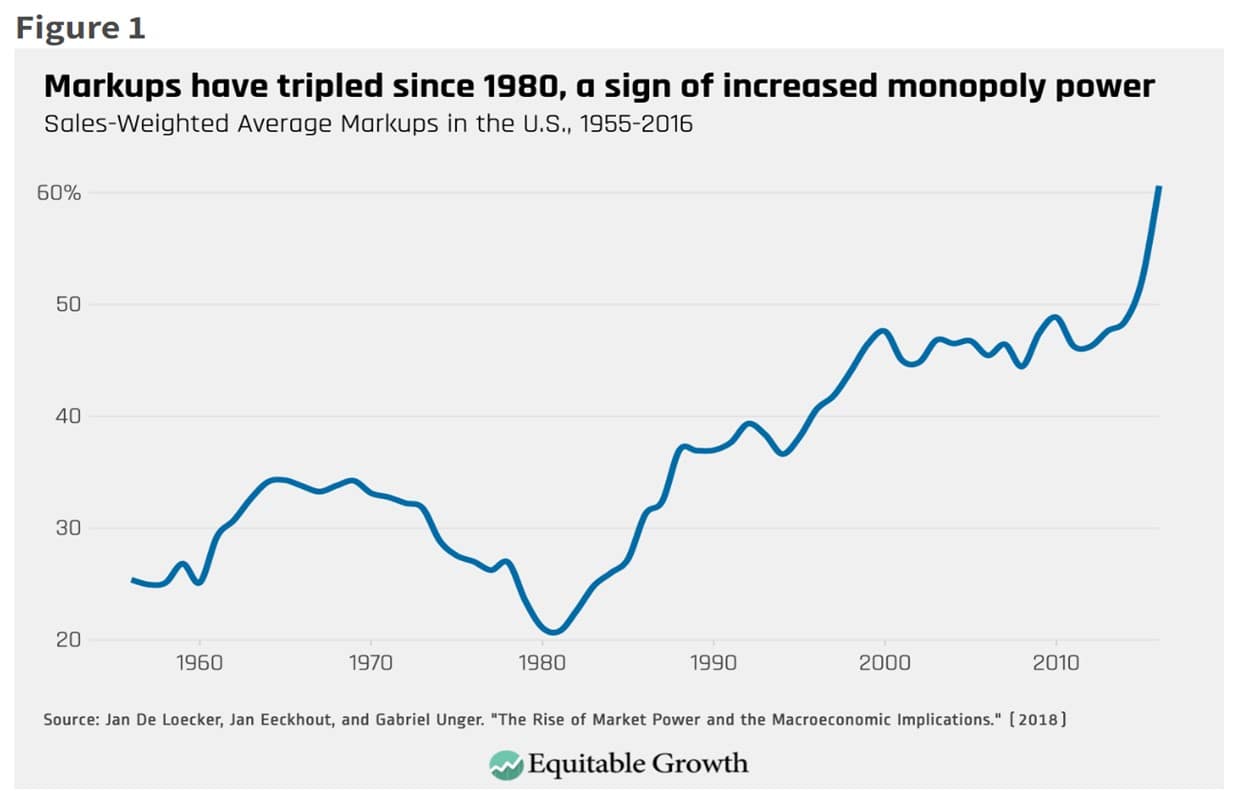

While it is true that Clinton’s inability to maintain the Democratic presidential hold on the so-called “blue wall” of old Midwest industrial states, such as Michigan and Pennsylvania, cost her the Electoral College, given her politically calculated capitulation on further free trade agreements, that abandoned position cannot coherently be held to blame for her loss. Still, the fact that Clinton’s team determined that support for the TPP would be costly in old labor strongholds of the American automobile heartland points to problem already indicated above: diffuse costs and concentrated benefits leading to the adoption of policies that benefit the few at the expense of the many. Even those deals that do get done are hardly “free trade.” An actual free trade agreement could fit on a bar napkin (like the eponymous “Laffer Curve”); what prevents this in large part is the political pressure within states by organized groups seeking such rents, whether through subsidies, exceptions, or other forms of protectionism such as tariffs or quotas, thereby causing agreements to run to thousands of pages. These mechanisms increase the market power of domestic firms, allowing them to charge much higher prices to their captive markets:

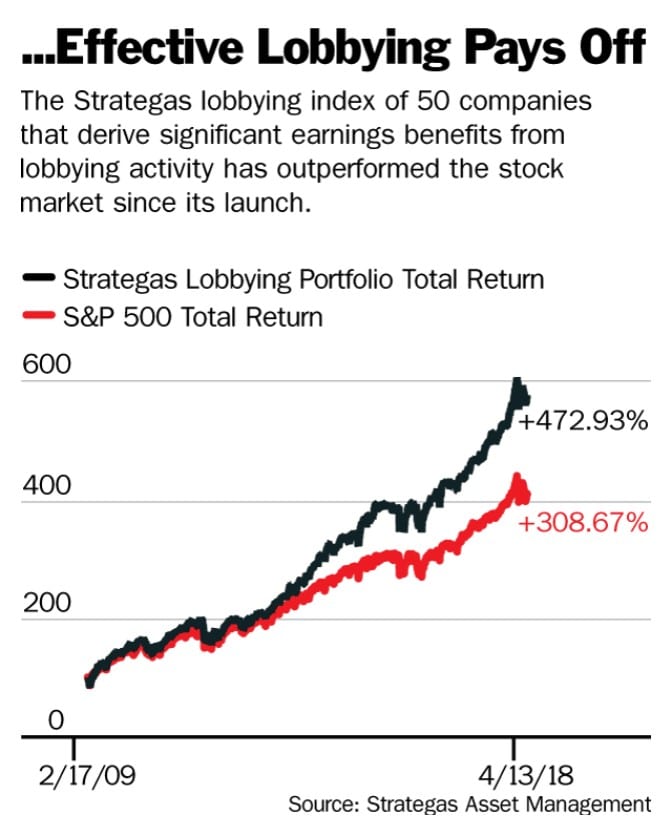

These higher prices translate into higher profits which can then be used to further influence the political process. From Rockefeller to Buffett, Peter Thiel spoke for many a capitalist when he flatly opined, “Competition is for losers.” Returns to corporations that invest heavily in lobbying suggest he is right:

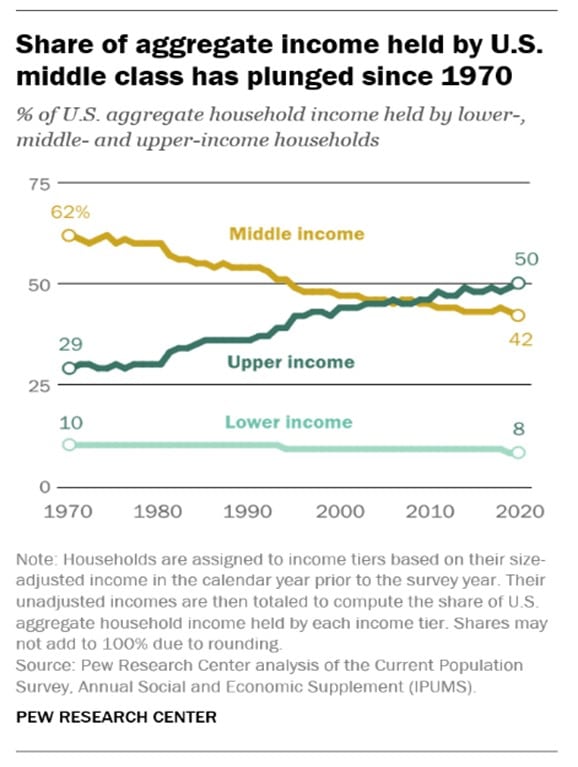

A combination of this lobbying, regulatory capture, and the revolving door—whereby high-ranking government officials and corporate executives move back and forth between government and the private sector, essentially writing the rules to govern how they will operate—has created an environment ripe for a populist backlash from both the right and left. When coupled with the obvious squeeze on the paychecks of regular Americans, this behavior has enabled the commensurate rise in the share of national income that goes to these highest earners rather than the middle and lower classes:

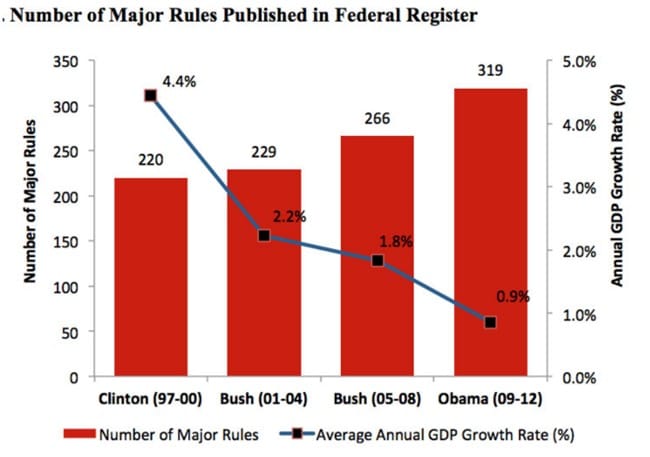

Indeed, in the ultimate irony, the namesake of economic liberalism par excellence, the “Washington Consensus,” has in fact become a haven of legalized cronyism. Using their political access to defend their positions—for example, using increased numbers of regulations as a means to create barriers to the entry of possible competitors—it is little wonder the last quarter century has seen a sharp decline in the number of new firms entering the U.S. market, and a rise in the number of regulations and restrictions facing possible new entrants:

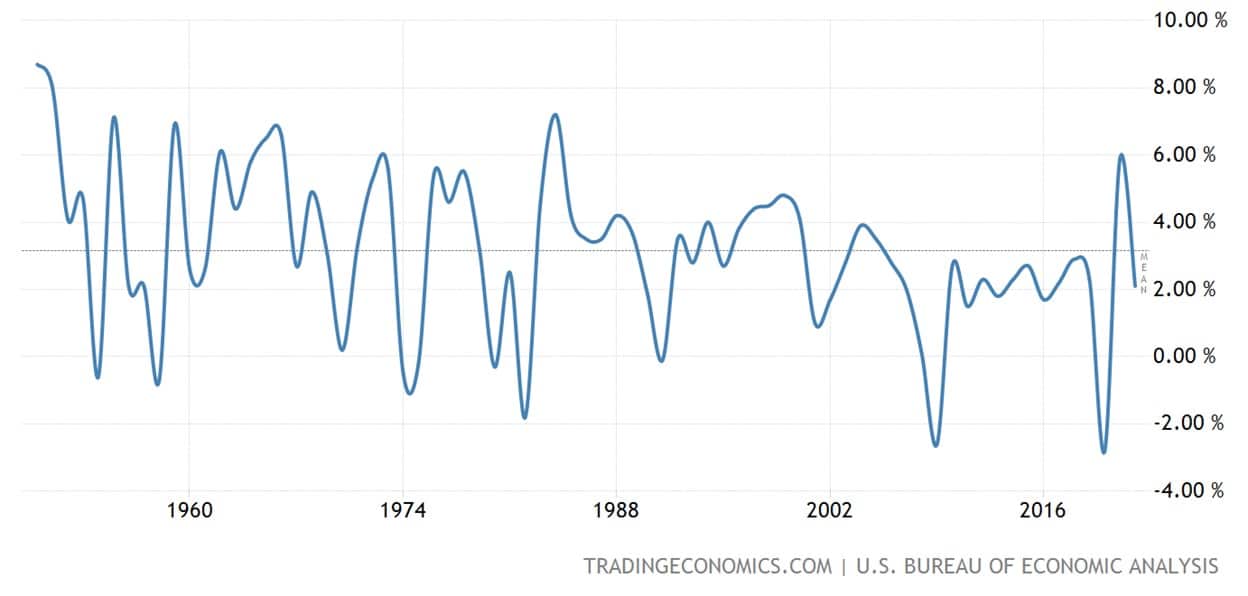

Unsurprisingly, this move away from openness has coincided with a fall in annual GDP growth below its historical mean as a mature economy:

Domestically, then, it is clear that what is needed is a return to the efforts of the 1990s toward balancing the budget, lowering marginal tax rates, and deregulating, as well as strongly pushing back against protectionism in all its guises.

It should be clear that, whatever its faults (for example, the causal link between abrupt changes in foreign capital flows and financial crises is well-established), the liberalization of domestic economies and of international trade has had many demonstrable benefits over the past half-century, and any drawbacks to increased liberalization should be viewed in the full context of the benefits derived from the increasing integration of global capital, labor, and goods markets.

Particularly in the present moment, when war between two or more of the so-called Great Powers looms more ominously than at any point for a generation, trade, existing commercial relationships, and foreign investment are among the few forces potentially powerful enough to steer states away from conflict. For while there are obviously certain industries that profit from war and preparation for it, and lobby accordingly, the notion that war is somehow favorable to business remains in the words of Norman Angell, The Great Illusion.

Hence, while representatives of the U.S. Navy and State Department speak openly of war and getting tougher with China, Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen is attempting to reassure Beijing that the United States has no intention of following through on calls to “de-link,” and major Western CEOs like Jamie Dimon and Elon Musk are hurrying to assure the Chinese of their continued desire to do business in the Middle Kingdom. Even close allies in security cooperation such as South Korea and Taiwan have successfully petitioned Washington for exemptions to DC’s attempt to shut down allies’ semiconductor operations in China.

Though no panacea (major trading partners have gone to war before), trade is a powerful, though not fool-proof, deterrent to war. In the words of the great nineteenth century liberal Otto T. Mallery in his Economic Union and Durable Peace, “If soldiers are not to cross international boundaries, goods must do so. Unless the shackles can be dropped from trade, bombs will be dropped from the sky.”

Following the guidance of their first president in his Farewell Address, Americans should heed George Washington and seek “liberal intercourse with all nations” while working to perfect the liberal experiment at home.