Though the conflict is little known in the United States, Chinese military planners have long obsessed over what lessons can be gained from studying the brief 1982 conflict between Argentina and Great Britain over the small collection of islands in the South Atlantic near the tip of South America—the Falklands—and for good reason. Its location, historical context, and the nature of the conflict between the powers involved more closely mirror the current standoff over Taiwan than any other example in modern war. Drawing lessons from history is a tricky business, however. And while Chinese military planners do well in studying the tactics of the conflict, U.S. foreign policy architects should be far more cautious. As will be presented below, presuming that by doing the opposite of what the British did in the case of the Falklands War that conflict will be averted or made less likely is not borne out in a comparison with the situation over Taiwan.

A hardscrabble collection of over seven hundred small islands, the largest and most predominant among them West and East Falkland, the Falklands lay less just nine hundred miles from the Antarctic circle and were uninhabited when the first European explorers began probing the southern cone of South America. Though the Spanish, English, and French all made various claims to the islands during the seventeenth century, by the eighteenth century Great Britain, with its superb navy, had proven most able to enforce its writ and had claimed sole possession of the islands as early as 1774. The outbreak of the French Revolution and later the Napoleonic wars, however, meant no one was home when the recently liberated Buenos Aires elites decided to stake a claim of their own and assert full authority—the islands being, after all, just three hundred miles out to sea. And so it was from 1816-1832 the islands were under Argentina’s control.

The British returned, however, and after a brief battle drove the Argentinians from the islands, in 1840 making them Crown colonies. With Britain ascendent and on its way to controlling, at its apogee, fully 25% of earth’s landed surface, Buenos Aires could do little but grumble bitterly. But here are the origins of the competing claims to the Falkland islands; claims that would continue to be disputed at a low diplomatic level at varying degrees of intensity over the next century and a half.

Fast forward to the second half of the twentieth century, with Great Britain exhausted by two world wars, its empire crumbling, revolting, or being otherwise abandoned, the Labor governments of the 1960s proved receptive to Peron’s more aggressive reassertions of Argentina’s claims over the islands. Discussions were slow, however, dragging on into the 1970s unresolved—hampered in large part by existing commercial interests on the islands and by a perception among U.K. voters of the essential Britishness of the Falklanders as part of “Greater Britain,” sharing a common language, culture, way of life, and other customs.

Economic realities were such, however, that by the late 1970s Great Britain had all but ceased involvement in the South Atlantic region and scrapped its only ship devoted to patrolling the area without replacing it. Having, then, in the years preceding the conflict, signaled a willingness to at least allow for the Falklands to fall into the Argentinian orbit, and then neglecting to maintain a forceful and visible presence, it is generally undisputed that the military junta that had seized power in Argentina in 1976 believed Thatcher’s government would do nothing were it to move to reclaim the islands. Therefore, facing rapidly declining popularity in the face of economic mismanagement, the junta decided the best way to offset the growing social unrest was a nice, short patriotic war in defense of a long-besmirched national honor.

Reasonable though this line of thinking was, it was all based on the premise that the U.K. leadership would not go to war over the Falklands: and this turned out to be a mistake.

For though the junta were correct that the British had been signaling apparent ambiguity regarding the fate of the islands, that they were completely unimportant militarily and economically to the home island. But what the Junta failed to understand was how their actions would impact the political incentive structure facing the embattled Thatcher government. Unpopular and struggling, whatever Thatcher’s actual feelings towards the Falklands, an election was just around the corner and the press and popular opinion made it impossible for her to do anything other than fight in defense of what was left of the empire. After being assured by the British military establishment that the islands could be retaken, Thatcher ordered a task force assembled and dispatched.

And so the war came.

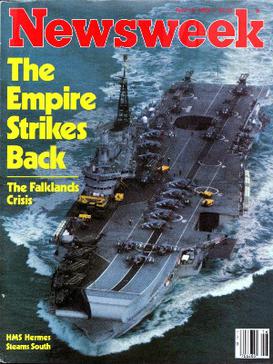

As innumerable books on the play-by-play of the military conflict describe—many of which were authored by participants in the events on the ground—even though the Argentinian armed forces were something close to a joke, its soldiers under-trained raw conscripts, and its military hardware equally substandard, the campaign was very nearly a disaster for Great Britain. They were unaccustomed by now to projecting force, and needed civilian ships to serve as transports. Approaching the occupied islands, the Royal Navy lost multiple ships to airstrikes launched from the mainland in the form of sorties, as well as Exocet missiles in the week and a half it took the British to both establish dominance of the surrounding sea and land significant numbers of troops. They ultimately succeeded in doing so after the Argentinian navy and air force abandoned the islands. Their comrades, now marooned, were left to face the British special forces alone. The rugged terrain meant the series of sporadic engagements that followed were of the running sort—with only a few pitched battles in all—and Great Britain retook the islands just 74 days after the Argentinian forces had invaded.

In short order the junta was overthrown, Thatcher was reelected, and the Falklands remained inside the British sphere.

In the case of the Falklands, it is almost certain that had Great Britain made its intention to defend the islands clear ahead of time the Argentinian junta would not have invaded. At the time, then-Senator Joe Biden was among the most vocal supporters of British military intervention. As a close observer of the conflict, and with a hawkish foreign policy team behind him, the lesson the Biden administration seems to have drawn as applied to Taiwan is that by making its intentions clear it will thereby avoid conflict with China. This shift away from the prior tactic of “strategic ambiguity” was evidenced by Biden’s statements following the botched Afghanistan pullout. Speaking to reporters about whether or not allies could still count on American security guarantees, Biden included Taiwan on a list that included the NATO countries and Japan.

The evidence suggests Biden is quite serious about this commitment. From the immediate high-level meetings between his administration and the countries of the QUAD, arming the Australians with submarines capable of snooping for long periods in China’s backyard, and arms sales to Taiwan, the message couldn’t be clearer: we’ll fight you so don’t even try. Key differences between the Falklands and Taiwan, however, cast serious doubt on this shift in tactics.

First, Argentina’s military hadn’t planned for a British counter-attack while the Chinese most certainly will have.

Second, Taiwan is much closer to mainland China and its missile batteries and airfields than were the Falklands to Argentina. Furthermore, the missiles China would be launching at American, Japanese, Indian, and Australian forces would be satellite guided and far more accurate and deadly.

Third, it is China that has the territorial claim and grievance. Granted, Beijing’s claim on the island is questionable, as it hasn’t been ruled by Beijing in over a century and was only added to the Chinese Empire in the late eighteenth century. But all that aside, it isn’t recognized by the international community as an entity outside China proper.

Fifth, the Argentinian population weren’t committed to a fight over the Falklands in the same way the Chinese are to Taiwan.

Sixth and finally, the Argentinian junta needed the signal of ambiguity from Great Britain because they rightly suspected they couldn’t stand up to it in a fight. China does not feel that way—if anything U.S. belligerence only serves to provoke a proud Chinese government and people into aggressive action in defense of their honor. Afterall, it isn’t a secret that in CCP propaganda Taiwan represents the final remnant of the “century of humiliations.”

In short, Biden’s shift in tactics from strategic ambiguity to a policy of strategic clarity represents a misapplying of the lessons of history. Doing what would have prevented a similar conflict in the past is no guarantee of success in the here and now. If U.S. strategy is aimed at maintaining peace in the region, its change in tactics seem likely only to undermine it.

Joseph Solis-Mullen is a graduate of both Spring Arbor University and the University of Illinois, and is a current graduate student in the Department of Economics at the University of Missouri. An author, blogger, and political scientist, his work can be found at the Ludwig von Mises Institute, Sage Advance, Seeking Alpha, and his personal website. You may contact him at theauthor@jsmwritings.com or follow him on Twitter.