Sunday was the 75th anniversary of the death of Franklin Roosevelt. Roosevelt was sainted by the media even before he died in 1945. CNN last week trumpeted FDR as “the wartime president who Trump should learn from.” A 2019 survey of historians ranked FDR as the third greatest president. President George H.W. Bush praised him for having “brilliantly enunciated the 20th-century vision of our Founding Fathers’ commitment to individual liberty.”

Roosevelt did often invoke freedom, but almost always as a pretext to increase government power. FDR proclaimed in 1933: “We have all suffered in the past from individualism run wild.” Naturally, the corrective was to allow government to run wild.

FDR declared in his first inaugural address: “We now realize… that if we are to go forward, we must move as a trained and loyal army willing to sacrifice for the good of a common discipline, because without such discipline no progress is made, no leadership can become effective.” The military metaphors, which practically called for the entire populace to march in lockstep, were similar to rhetoric used by European dictators at the time.

Roosevelt declared in a 1934 fireside chat: “I am not for a return of that definition of liberty under which for many years a free people were being gradually regimented into the service of the privileged few.” Politicians like FDR began by telling people that control of their own lives was a mirage; thus, they lost nothing when government took over. In his re-nomination acceptance speech at the 1936 Democratic Party convention, Roosevelt declared that “the privileged princes of these new economic dynasties . . . created a new despotism. . . . The hours men and women worked, the wages they received, the conditions of their labor—these had passed beyond the control of the people, and were imposed by this new industrial dictatorship.” But if wages were completely dictated by the “industrial dictatorship”—why were pay rates higher in the United States than anywhere else in the world, and why had pay rates increased rapidly in the decades before 1929? FDR never considered limiting government intervention to safeguarding individual choice; instead, he multiplied “government-knows-best” dictates on work hours, wages, and contracts.

On January 6, 1941, Roosevelt gave his famous “Four Freedoms” speech, promising citizens freedom of speech, freedom of worship—and then he got creative: “The third [freedom] is freedom from want… everywhere in the world. The fourth is freedom from fear . . . anywhere in the world.” Proclaiming a goal of freedom from fear meant that the government henceforth must fill the role in daily life previously filled by God and religion. FDR’s list was clearly intended as a “replacement set” of freedoms, since otherwise there would have been no reason to mention freedom of speech and worship, already guaranteed by the First Amendment.

Roosevelt’s new freedoms liberated government while making a pretense of liberating the citizen. FDR’s list offered citizens no security from the State, since it completely ignored the rights guaranteed by the Second Amendment (to keep and bear firearms), the Fourth Amendment (freedom from unreasonable search and seizure), the Fifth Amendment (due process, property rights, the right against self-incrimination), the Sixth Amendment (the right to a speedy and public trial by an impartial jury), the Eighth Amendment (protection against excessive bail, excessive fines, and cruel and unusual punishments).

FDR perennially glorified government as the great liberator of the common man. In a 1936 message to Congress, he denounced his critics: “They realize that in 34 months we have built up new instruments of public power. In the hands of a people’s government this power is wholesome and proper. But in the hands of political puppets of an economic autocracy such power would provide shackles for the liberties of the people.” Because FDR proclaimed that the federal government was a “people’s government,” good citizens had no excuse for fearing an increase in government power. The question of liberty became totally divorced from the amount of government power—and instead depended solely on politicians’ intent toward the governed. The mere fact that the power was in the hands of benevolent politicians was the only safeguard needed.

Roosevelt sometimes practically portrayed the State as a god. In his 1936 acceptance speech at the Democratic National Convention, he declared, “In the place of the palace of privilege we seek to build a temple out of faith and hope and charity.” In 1937, he praised the members of political parties for respecting “as sacred all branches of their government.” In the same speech, Roosevelt assured listeners, in practically Orwellian terms, “Your government knows your mind, and you know your government’s mind.” For Roosevelt, faith in the State was simply faith in his own wisdom and benevolence. Roosevelt’s concept of the State is important because he radically expanded the federal government— and most of the programs he created survive to this day.

FDR declared in 1938, “Let us never forget that government is ourselves and not an alien power over us. The ultimate rulers of our democracy are not a President and senators and congressmen and government officials, but the voters of this country.” Did Japanese-Americans round themselves up for concentration camps in 1942, or what? Did the people who owned the gold that FDR forcibly confiscated in 1933 secretly will that they be stripped of any defense against the inflation that FDR intentionally ignited?

FDR’s perpetual deceits on domestic policy are grudgingly recognized by some scholars but his brazen lying on foreign policy has not received its due. in 1940, in one of his final speeches of the presidential campaign, Roosevelt assured voters, “Your president says this country is not going to war.” But FDR was working around-the-clock to pull the United States into World War Two. Once the U.S. was engaged in fighting both Germany and Japan, FDR was determined to demand unconditional surrender from both nations. That demand severely undercut German generals who were reaching out to strike a deal with the Allies that would have toppled Hitler much earlier than April 1945. Thomas Fleming’s The New Dealers War vividly explains how FDR’s war demands perpetuated the fighting and cost the lives of far more Americans, Germans, and others.

Two months before he died, FDR met Stalin and Churchill for the infamous Yalta conference. Roosevelt had previously praised Soviet Russia as one of the “freedom-loving Nations” and stressed that Stalin is “thoroughly conversant with the provisions of our Constitution.” FDR agreed with Stalin at Yalta to move the border of the Soviet Union far to the west—thereby effectively conscripting 11 million Poles into Soviet citizenship.

Poland was “compensated” with a huge swath of Germany, a simple cartographic change that spurred vast human carnage. As author R.M. Douglas noted in his 2012 book Orderly and Humane: The Expulsion of the Germans After the Second World War, the result was “the largest episode of forced migration… in human history. Between 12 million and 14 million German-speaking civilians – the overwhelming majority of whom were women, old people, and children under 16 -were forcibly ejected from their places of birth in Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Romania, Yugoslavia, and what are today the western districts of Poland.” At least half a million died as a result. George Orwell denounced the “relocation” as an “enormous crime” that was “equivalent to transplanting the entire population of Australia.” Philosopher Bertrand Russell protested: “Are mass deportations crimes when committed by our enemies during war and justifiable measures of social adjustment when carried out by our allies in time of peace?”

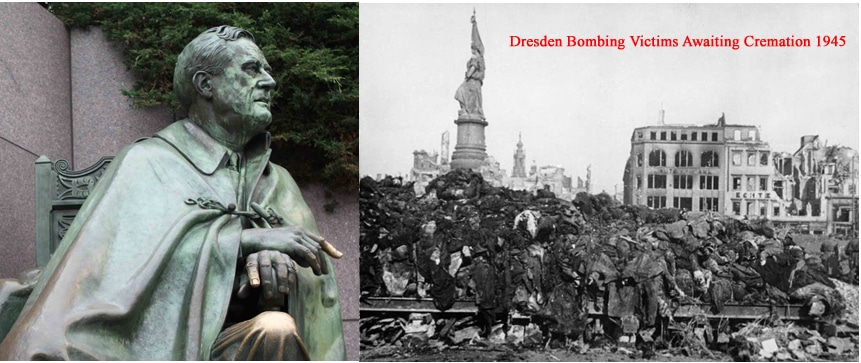

In a private conversation at Yalta, FDR assured Stalin that he was feeling “more bloodthirsty” than when they’d previously met. Immediately after the Yalta conference concluded, the British and American air forces turned Dresden into an inferno, killing up to 50,000 civilians. The Associated Press reported that “Allied air bosses” had engaged in the “deliberate terror bombing of great German population centers as ruthless expedient to hasten Hitler’s doom.” Ravaging Dresden was intended to “‘add immeasurably’ to FDR’s strength in negotiating with the Russians at the postwar peace table,” as historian Thomas Fleming noted.

Almost all the tributes to FDR this month have omitted his dictatorial tendencies or his bloodthirsty warring. There were good reasons why Friedrich Hayek labeled FDR as “the greatest of modern demagogues.” The canonization of Franklin Roosevelt is a reminder to Americans to beware of any “lessons of history” touted by an establishment media that is vested in the perpetuation of Leviathan and all its prerogatives.