An examination of Chinese foreign policy historically lends little support to those who depict China as secretly plotting to take over the world. Rather, it points to an entity preoccupied with managing its complex, local strategic environment and internal security concerns. While no single article devoted to the subject can comprehensively make such a case in detail, a few general observations are worth pointing out for their relation to the present. Despite what proponents of the New Red Scare would have us believe, China and its nominally communist leadership have for decades acted in a way that is strictly nationalist ideologically. It is therefore important to understand what, to borrow Palmerston’s phrase, China’s eternal interests are and how they have been pursued.

Surrounded on virtually all sides, the history of Chinese foreign policy is one of permanent flux, of an ever-changing external security environment made more complex by the actually quite heterogeneous makeup of the peoples and lands that constitute the core of China historically. In contrast to th nation state, being a relatively modern creation of Europeans and globalized during the Age of Empire and its aftermath, “China” existed less as a specific geographical entity than as a cultural entity, a civilization rather than a state, to borrow from the American political scientist and Sinologist Lucian Pye.

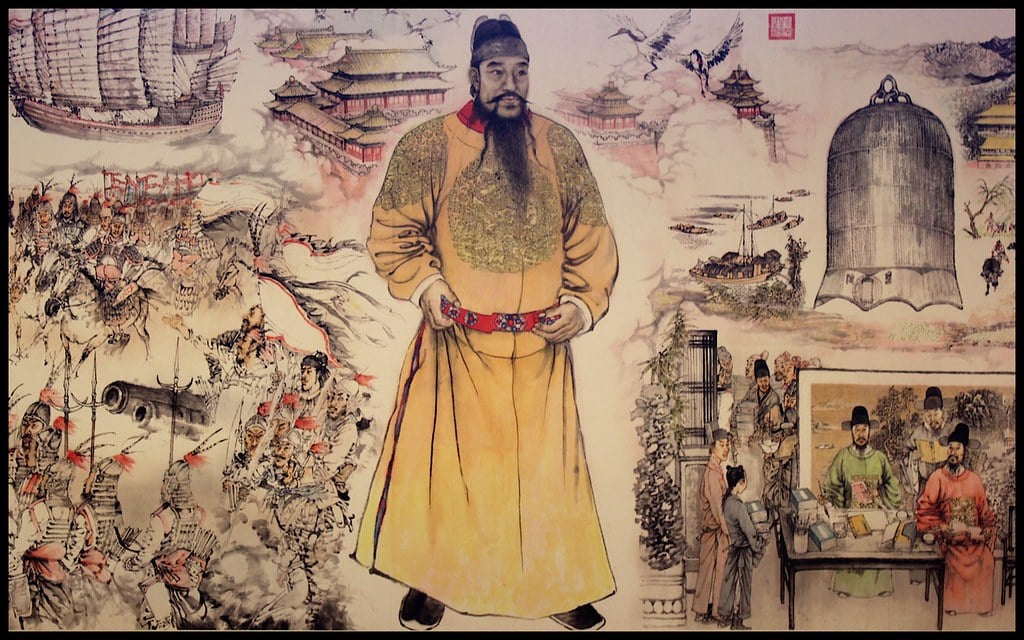

That civilization had at its core the Han of the Yellow River valley, Confucianism, and under the later Sui (581-618), Tang (618-906), and Song (960-1279) dynasties the formalization of a meritocratic bureaucracy filled by way of a civil service examination to run the Imperial system. Its elite were centralized and bureaucratic rather than decentralized and militaristic. While this reduced the tendency of earlier periods toward fragmentation under competing warlords, it made China vulnerable to attack by the many surrounding “barbarians” (i.e. non-Sinicized people).

One common solution to this problem was, to quote the Chinese-American Sinologist Yang Lien-sheng, “using barbarians to check barbarians” or “using barbarians to fight barbarians.” (33) When this failed, however, conquering barbarians were often effectively Sinicized as easily as though it were they that had been conquered and not the other way around. The Mongol Yuan (1279-1368) and Manchu Qing (1644-1911) dynasties were examples of this reverse assimilation, undergone by the new ruling class as a way to ensure their effective control over a vast and complex territory.

While the Chinese state did, over the course of its thousands of years of history, multitudinous dynasties and instantiations, go through local periods of expansion via conquest or colonization, the geographical difficulties, costliness, and uncertainties of attempting to project and sustain concentrated military power on so many fronts meant the favored Chinese order was one which saw China as central but by no means all-encompassing or even truly hegemonic. Independent kingdoms in Vietnam, Japan, and Korea were established facts, with any tribute, in the words of Asian Studies professor Henry Em, often being little more than nominal. (23)

While its cultural and economic influence in east Asia was significant, and its view of itself as the center of civilization was understandable given its preponderance, material wealth, and technological superiority, Chinese foreign policy was not concerned with expanding its trade, culture, or territorial reach much beyond its immediate environs.

Its attention focused inward, with external trade largely eschewed, and advances in military and naval affairs either unpursued or abandoned, the Western powers first began more assertively to try and open up China in the nineteenth century. Seeking trading concessions, privileges for their nationals, and permanent diplomatic presences, the reaction of the Imperial government to western outreaches was an attempt to follow the time-tested template of using barbarians to fight barbarians; inviting the French, Americans, and Russians so that they might fight with one another and thereby become weak enough that they might all be ejected.

This, of course, did not happen—as the ambition of these barbarians was not to conquer and rule China but to extract resources from it. Far from eager to see the Imperial government in Beijing fall, the Western powers helped to prop it up, understanding like the Manchu and Mongols before them that the vastness and complexity of the empire required a military and bureaucratic capacity beyond any of them. Despite their efforts, however, the loss to Great Britain and its allies in the Opium Wars (1839-42 and 1856-60), and their consequent “unequal treaties,” sparked off multiple internal rebellions (1850-64, 1851-68, 1856-72, 1862-67, 1895-96, and 1899-1901) as imperial legitimacy was tainted and central authority weakened.

The dawning of the twentieth century saw Revolution (1911-12), betrayal by their Western allies at Versailles (1919), warlord-ism (1916-28), invasion by Japan (1931), the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-45), and concurrent Civil War (1927-49). In short, the so-called “Century of Humiliation” (1839-1949) saw a China unable to act independently; and it was not until the eventual triumph of Mao’s Chinese Communist Party that China began, in his words, to “stand up.”

Western observers were surprisingly slow to recognize the ideological significance of the communist states fighting with one another: particularism, not universalism, was to be communism’s defining feature (note: even earlier it should have been telling that Stalin, to muster support for war against the Nazis, had called on Russian patriotism, not Marxist doctrine.)

Historical memory, as well as Stalin’s own hard driving realism in his negotiations with Mao, meant Sino-Soviet relations were always going to be precarious rather than fraternal. And when Khruschev turned on Stalin after the dictator’s death, Mao used the opportunity to assert China’s definite autonomy, denying the Soviets access to Chinese territory and eschewing cooperation. Competing for influence in the various revolutionary hotspots abroad further soured relations, as did Soviet backing for India.

Mao’s eventual decision to try opening to the United States, therefore, was prompted by the long-term deterioration in Sino-Soviet relations as well as a recognition of China’s national strategic interests. And as war with the Soviet Union became increasingly likely in the late 1960s, Mao sought an opening on the basis of a classical strategy of Chinese history: engaging the far enemy while fighting the near.

Engagement with the United States had the additional benefit of helping make China rich again; and especially with the disappearance of a common foe and the immediate examples of U.S. military unilateralism in the 1990s, Chinese leaders began to use China’s newfound wealth and technological capabilities to harness an anti-access/area-denial strategy to protect and preserve its regained autonomy, a capability it lacked for centuries and which in effect made the South China Sea into a Western lake.

A policy of “Full Spectrum Dominance” this is not. Rather, China has sought ways to asymmetrically push back against the superior forces deployed against them in defense of their long-standing interests.

It seems incredible that more than thirty years after the fall of the Soviet Union and decades after the Chinese embrace of state capitalism, that anyone could fall for the obvious and worn tropes of the dangers of “communists” taking over the world. And yet each day millions of Americans now tune in to lurid descriptions of the allegedly perfidious activities of, not Beijing or Xi or China, but the Chinese Communist Party.

But this is nonsense. Xi rouses the population with nationalist talk, not Marxist or Maoist talking points. National pride aside, he and his cronies are interested in enriching themselves and being in power, and much like being a member of the Republican or Democratic Party, are required to effectively loot the country.

As Samuel Huntington observed in 1996, a reconstituted and powerful China interested in resurrecting its classical sphere of influence was already a “cultural and economic reality” in the process of becoming “a political one.” (169) Tellingly, he went on to predict: “The dangerous clashes of the future are likely to arise from the interaction of Western arrogance…and Sinic assertiveness.” (183) For, “What is universalism to the West is imperialism to the rest.” (184)

This prescience aside, if FDR could cut deals with Stalin, and Nixon could sit down with Mao, Joe Biden or Donald Trump should be able to get along with the likes of Xi (or Putin for that matter), lest a clash of civilizations end civilization entirely.