“I must follow the journalistic instinct of being skeptical of everything until I personally have proved it true.”- Irwin Fletcher

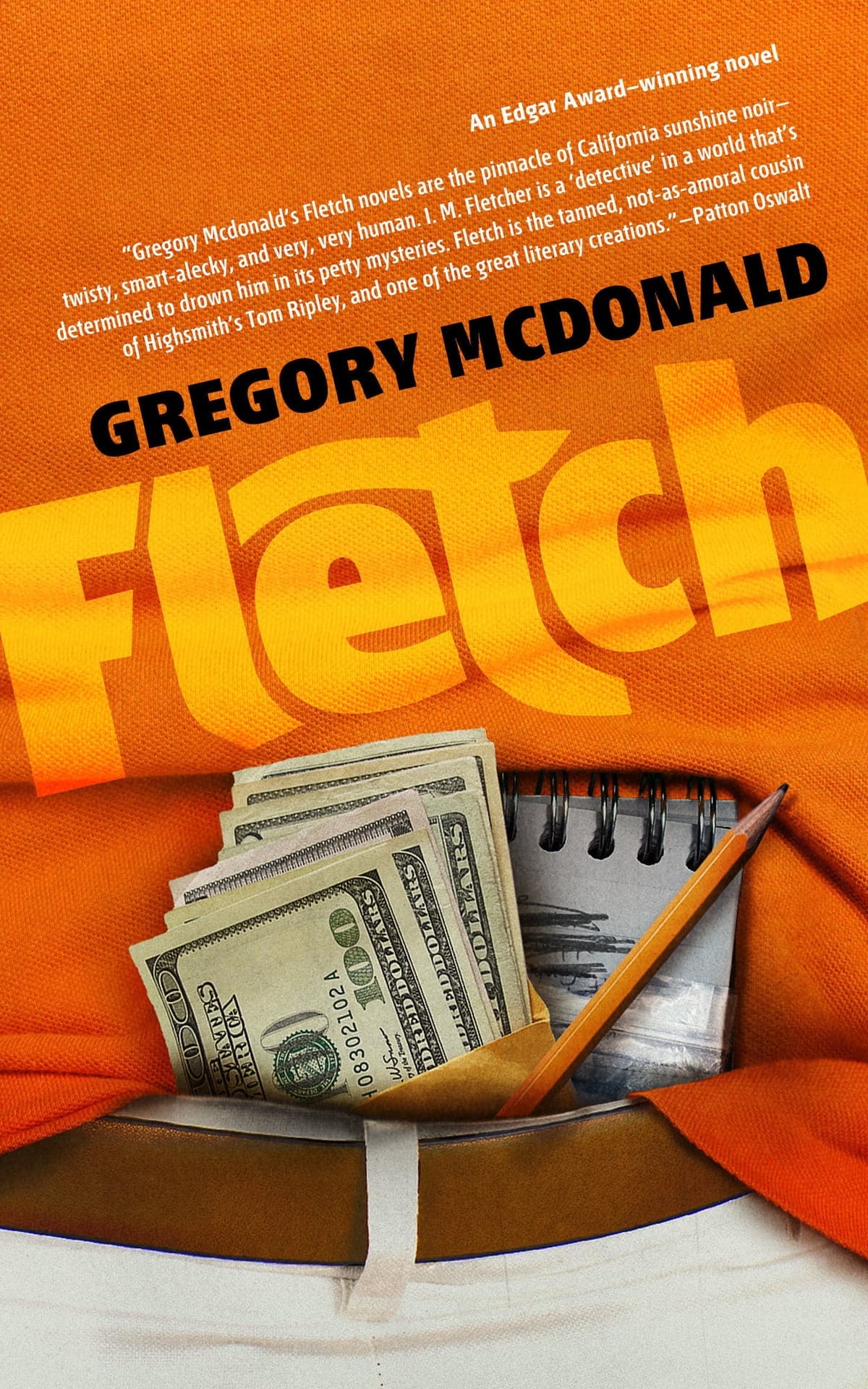

In the post-Watergate world, fiction was full of lone wolf reporters, the courageous typewriter and camera that pointed where it was unwelcome. When author Gregory McDonald wrote his first “Fletch” novel in 1974 about reporter and former marine Iriwn M. Fletcher (AKA “Fletch” or “Jane Doe”), it would develop into a series of books, two movies starring Chevy Chase, and a remake to be released this year.

In the first book and movie, a world of police corruption is unravelled after a man approaches Fletch, requesting that the undercover reporter murder him so that he can claim insurance for his family. The man alleges to be dying of bone cancer. This request stirs a curiosity in Fletch which unravels a plot of double cross, fraud, and a police supplied drug epidemic.

Written in a time when even the highest office was no longer above investigation and condemnation, Fletch followed his instincts, writing on what he discovered while undercover risking reputation, income, and his life. Though for a time it was celebrated, when Daniel Ellsberg endured similar risk when he turned over the Pentagon Papers. The New York Times then published the information, revealing the hubris and depth of deception that the U.S. government possessed in its war on South East Asia. The editorial staff of the Times could have sat on the information and participated with the government, and perhaps in the twenty-first century they may very well have done so. Actions like Ellsberg’s, once celebrated, landed Julian Assange of Wikileaks in prison awaiting extradition.

Do not confuse courage and integrity for truth with moral character. The book version of Fletch is not a good man. In the first novel he uses a fifteen-year old addict, including having sex with her. His empathy for her was related to what information she could provide. She was not a human being, only a source. When she dies, he loses the information that she carried with her. The singular pursuit of revealing information can easily be romanced and seem noble. It can also come at a cost to human dignity and the human ability to compromise to the greater good. One teenage junkie can be sacrificial beneath a greater story. Fletch even takes the money and runs after exposing the corruption, only to return where he almost began in the subsequent novels. Fletch is cynical and written from the purgatory of distrust and numbness. Maybe that is where we are now.

The 1980s would celebrate the tradition of the rogue reporter, romancing them with an adventurer’s avatar who dodges bullets, suffers torture, and conducts espionage like James Bond in order to find the facts and reveal evil. They were champions of the innocent, heroic untouchables who were incorruptible and fearless. Whether it was James Woods in Salvador or Nick Nolte in Under Fire, these were individuals of courage. The media did not have to be a propaganda mouth piece for the regime of rules or advertising copy announcers. The relationship between the suffering and the general public required a conduit of reporters to weaken the powerful, shame them, and even over throw them. It was the aftermath of Bernstein and Woodward, names of now journalistic fame thanks to their efforts in breaking the Watergate scandal.

The massacre of innocent civilians in My Lai, Vietnam was a sobering reality for those who were able to read about it. The rape and murder of women and children by U.S. soldiers could have been another event of unmarked graves if it was not for the investigative curiosity of journalist Seymour Hersh. The U.S. government had been keeping details of the massacre concealed when Hersh heard rumors about the court martial of Lieutenant William Calley for his role in the murders. Once Hersh had interviewed and investigated, he reported on a dangerous event that undermined the U.S. government’s policy in Vietnam. Sparking criticism and reactions all the way up the White House, the courageous pen of a reporter challenged the highest authority again and reported the truth.

Men like Robert Fisk lived this life, though he would die at a time when reporters like him became a rarer species. He was a man not seduced by becoming embedded with “friendly forces” or those loyal to a particular side in a war.

We are fortunate to have many who still continue this legacy, risking themselves for the pursuit of truth. In the case of Shireen Abu Aqleh who was likely assassinated by the Israeli military while she was covering an IDF raid in occupied Palestine, or the brutal murder-torture of Jamal Shashoggi by the Saudi government, not to mention the many reporters murdered in horrific manners and numbers by cartels in Mexico, terrorists, criminals, and governments alike often target journalists and reporters for the words that they write. Failing that as a threat, censorship and professional practices within media organisations act as another deterrent to ensure a bias and loyal media towards the government or a particular regime.

Modern technology and access to the internet has given many of us the ability to seek out those who report the truth for us. They exist (if one is willing to look for them). They may specialize in certain subjects or they may be broad with a curiosity for information. They may focus on corporate corruption and misconduct, or to the crimes of specific national governments. As the reader and distant voyeur we have the ability to hear and read them, to witness from afar the horrible things being done by those who are powerful and have so much control against the lives on others. Many of them are independent and rely upon the private donations and support of their readership, free of the editorial interests of corporate or government regulations.

So as the new Fletch movie comes out, perhaps we can celebrate the tradition of the past by championing Julian Assange, who in decades past would have been considered a hero. He is a champion for free information and truth, no matter how hideous or dangerous it may be. But with more access to media and information the mainstream culture has turned away from a desire to be informed from as many sources as possible. Instead, it prefers generating a digital realm of bias and comfort input. It’s undesirable to be challenged, to read or hear the truth even (especially) when it goes against the grain. Instead such a media culture keeps men like Jimmy Saville protected until his death and a man like Julian Assange behind bars because he published the facts about war crimes and corruption. A good journalist puts a mirror to the face of power, evil, and society itself. How we react to that reflection says more about us than those who hold up the mirror.

“Four hostile newspapers are more to be feared than a thousand bayonets…”- Napoleon Bonaparte