How nations approach foreign policy, including war, shifts dramatically with time. A shift in American foreign policy seems to be speeding up or, perhaps, the change is merely reaching the logical conclusion of policies developed in the post-World War II decades. Since the 1990s, there has been a growing interest in the relationship between geopolitics, such as territorial incursions, and geoeconomics, such as economic sanctions.

The preceding are stripped down definitions of “geopolitics” and “geoeconomics” that apply specifically to foreign policy or war; various sources would offer different ones. Some “clarifications” actually confuse the meaning further. The Marxist economist Max Beer (1864-1943) tried to explain the effects of global markets on working class consciousness, for instance:

“There is, indeed, an interaction between matter and mind. In this interaction the geo-economic conditions are the legislative, the mind is the executive; the material factors precede, the mind follows, interprets, transforms external facts into logical truths and ethical maxims, and then into motives of the actions of man…Still, both sets of conditions are so closely interlaced with each other that we may call them geo-economic conditions, always, however, bearing in mind that the economic elements are the more active and fluid.”

Whatever definitions are used, however, these are terms we are likely to hear more frequently and ones upon which policy will be based. Often, the policies will be justified by reassuring words like “deterrence,” “patriotism,” and “stability.”

In 2016, an influential book by scholars Robert D. Blackwill and Jennifer M. Harris, War by Other Means: Geoeconomics and Statecraft appeared from the Council on Foreign Relations. It argues a commonly heard position. “Russia, China, and others now routinely look to geoeconomic means, often as a first resort, and often to undermine American power and influence…The global geoeconomic playing field is now sharply tilting against the United States and unless this is corrected, the price in blood and treasure for the United States will only grow.” Blackwill and Harris contend that the United States must merge economic and financial instruments with its foreign policy or risk losing ground as a world power. This is their definition of geoeconomics and necessary statecraft: the tilting of the global economy to preserve a particular nation’s power and influence.

A concrete example of this sort of partnership is the BRICS New Development Bank (NDB), with the financial system’s foundation being laid about ten years ago by the governments of Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa. Its geopolitical purpose was to sidestep the world’s default currency (U.S. dollars) and banking system (Swift) that was being used by the United States and other Western nations for political advantage. Another example of geoeconomic active is the freezing of hundreds of billions of Russian assets in the European Union in response to the 2022 invasion of Ukraine. One geopolitical purpose was to apply political pressure on Russia. Another was to finance the war in Ukraine without draining the EU economy; this has already started. A headline in ABC News reads “EU sends first $1.6 billion from frozen Russia assets to Ukraine.” And, so, financial institutions move one step closer to becoming practical extensions of foreign policy.

In one sense, the foregoing approach to foreign policy is correct. An intimate connection does exist between geopolitics and geoeconomics. Unfortunately, the conclusions advanced about this connection are disastrously wrong.

What is the correct connection?

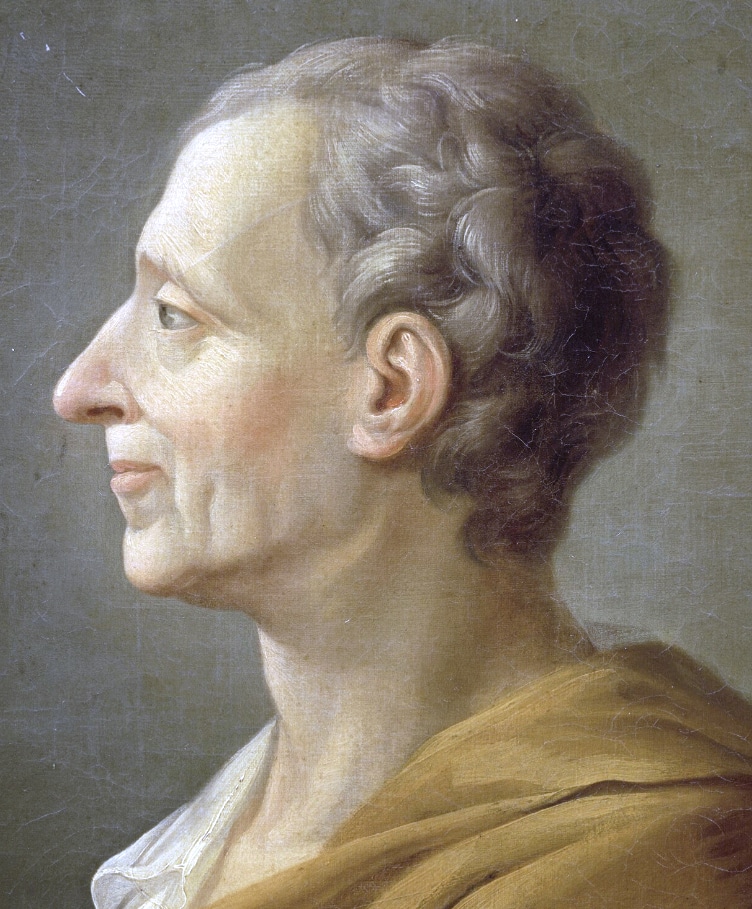

Charles Louis de Secondat, Baron de La Brède et de Montesquieu is usually referred to simply as Montesquieu. In his influential book Spirit of the Laws, the eighteenth century French political philosopher argued, “The natural effect of commerce is to lead to peace. Two nations [or individuals] that trade together become mutually dependent: if one has an interest in buying, the other has an interest in selling; and all unions are based on mutual needs.” This concept is called “doux commerce” or “sweet trade” in which a thriving global market place is recognized as a civilizing factor that increases the prosperity of all who participate in it.

As for deliberating pitting one man against another in some name of patriotism, as Blackwill and Harris seem to suggest, Montesquieu wrote, “If I knew of something that could serve my nation but would ruin another, I would not propose it to my prince, for I am first a man and only then a Frenchman…I am necessarily a man, and only accidentally am I French.” His humanitarianism was stronger than his concern for promoting a government’s self-interest.

“War by other means” is a different model of global interaction that seeks to strengthen an ally or to damage an enemy without resorting direct military conflict. The strategy diametrically opposes “sweet trade” as it usually involves tariffs, blockades, or other economic sanctions. The other means also include conventional indirect warfare, such as propaganda and espionage, but it increasingly includes the forging of geopolitical-geoeconomic relationships.

It is not possible to pinpoint n historical starting date of “war by other means” since strategies like starving a blockaded enemy into submission are probably as old as human conflict itself. Harry S. Truman’s assumption of the presidency after the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1945 is an important moment, however. Both American power and global communism were surging back then, with many Americans viewing the Soviets as “the new ultimate enemy.” Containment of communism became America’s main foreign policy goal. The Truman Doctrine (1947) and the Marshall Plan (1948) massively accelerated the linking of geopolitics and geoeconomics. The Truman Doctrine established aggressive programs to counter communism through strategies such as bribing governments and propping up pro-American regimes. The Marshall Plan transferred huge blocks of wealth from American to Western Bloc nations in Europe; this was deemed to contain communism, which Truman believed grew out of poverty. Thus, from 1947 to 1989, the so-called Cold War laid groundwork for “war by other means” to become embedded in the foreign policies of various nations.

Again, the Truman view of peace and stability is utterly incompatible with that of Montesquieu; the existence of one approach would eventually destroy the other. And Truman’s approach would also damage the civil society of any nation that adopted it. Why? The Spirit of the Laws explains a main reason; “Commerce is a cure for the most destructive prejudices; for it is almost a general rule, that wherever we find agreeable manners, there commerce flourishes; and that wherever there is commerce, there we meet with agreeable manners. Let us not be astonished, then, if our manners are now less savage than formerly. Commerce has everywhere diffused a knowledge of the manners of all nations; these are compared one with another, and from this comparison arise the greatest advantages.” A nation that attempts to preserve its global power and influence through the Blackwill and Harris strategy is actually walking a path to self-destruction.

Some people consider geoeconomics to be preferable to geopolitics because it reaches for a purse rather than for a gun. But a cursory examination debunks this position. For one thing, the choice is not an either/or one between two bad scenarios—that is, either plunder economies or secure advantages at the point of a gun. Moreover, both choices are being made today because they act to support of each other. The real choice is freedom, especially the “doux commerce” of individuals who trade value for value and so have no need for bribes or bullets.