In Economic Facts and Fallacies (2011), Thomas Sowell argues that housing regulation and zoning laws, not markets, are to blame for the modern scourge of unaffordable housing. Sowell is still right. Government housing regulations have exacerbated construction costs, reduced the elasticity of the housing supply, and worsened the vicious problem of homelessness.

A 2014 NBER (National Bureau of Economi Research) review of the current housing regulation literature confirmed what economists already knew: “regulation appears to raise house prices, reduce construction, reduce the elasticity of the housing supply, and alter urban form.” Complying with regulation is not only time consuming, but often requires detailed knowledge of local bylaws and the purchase of expensive permits. Restrictive zoning laws are particularly egregious, frequently and unnecessarily rendering certain areas unusable for housing. However, many seem to be unconvinced of the significance of this problem, preferring to blame rich investors, unsustainable population growth or growing incomes. Wouldn’t local regulations be unimportant compared with macroeconomic trends? Such claims are inconsistent with the evidence. A Reserve Bank of Australia working paper found that, “as of 2016, zoning raised detached house prices 73% above marginal costs in Sydney, 69% in Melbourne, 42% in Brisbane and 54% in Perth.” We know that regulations push up prices. Furthermore, they are frequently more influential than any demand side factor commonly blamed in the media.

In the 1970s, Californian governments regulated housing markets on a level not previously seen. Unsurprisingly, house prices exploded. This explosion cannot be blamed on population growth: over a ten year period starting in the 1970s, the average Palo Alto house price nearly quadrupled while population growth in that region was close to zero (Sowell 2011). The Las Vegas population almost tripled between 1980 and 2000, yet “real median house prices did not change” (Glaeser, Gyourko, and Saks 2005).

This takeoff cannot be blamed on incomes, either. Dallas has consistently achieved a growth of household incomes roughly 10 percent higher than the US average, while its house prices are generally lower than the US average (O’Toole 2006); the same is true of Houston. In the 1970s, real income in California grew more slowly than the national average, yet the takeoff took place (Sowell 2011).

Nor can this takeoff be blamed on inflation. The Foster City housing project of the 1960s (San Mateo, California), sold houses at prices between $22,000 and $50,000. In 2005, the average Foster City home price exceeded $1 million (Sowell 2011). These price increases dwarf the effects of inflation. In a ranking of America’s least affordable housing markets, seventeen were located in California. In a 2018 ranking, California was the third least affordable state in the US. Texas, the second largest economy behind California, was ranked twenty-third.

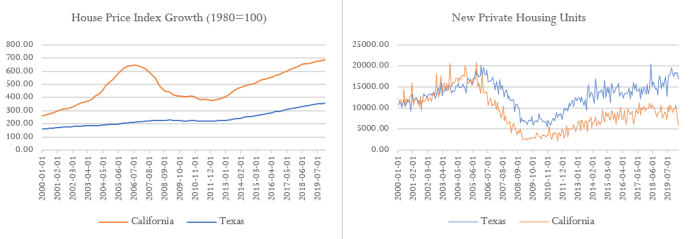

One need only compare house prices in California with those of Texas to see the lasting scars of so-called smart planning. Over the last twenty years, the Texas population has increased faster than that of California, and real GDP growth has been roughly the same in both states. Yet Californian house prices have grown faster ever year (see figure 2). The story becomes even clearer when we focus on individual cities. Despite being the fourth largest city (by population) in the US, the Houston market is ranked twenty-fourth in the world for affordability among major cities (those with populations greater than 1 million). This remarkable achievement can be largely attributed to the fact that Houston has no zoning laws.

Texas is not alone. Japan teaches us that population size does not dictate affordability. In the below table, we compare Tokyo with London.

| Urban Area | Tokyo | London |

|---|---|---|

| Population Density | 6,158 per square kilometer (source) | 5,701 per square kilometer (source) |

| Average Annual Salary (USD) | $50,655 (source) | $52,000 (source) |

| Monthly Housing Costs (USD) | $1,951.5 | $2,547.8 |

| Housing Price World Ranking | 16th | 5th |

Tokyo is the largest city by population in the world, with 37,435,191 people. But when world cities are ranked from highest house prices to lowest, Tokyo is sixteenth. Tokyo housing is more affordable than in Hong Kong, Paris, New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, Sydney, and Zurich. Over the last twenty years, Japanese real residential property prices have declined by roughly 1.40 percent per quarter. Over the same period UK and US real residential property prices have increased by 3.73 and 2.03 percent, respectively (see here). This incredible outcome is a consequence of Japan’s dynamic and deregulated housing market. Zoning regulations in Tokyo involve setting limits on nuisance levels rather than specifying how specific land can be used. Almost all Japanese property can be used for mixed developments; even in areas that are zoned as “industrial” there is nothing to stop a developer constructing a housing complex for willing buyers. Unlike other parts of the world where height restrictions are absolute, in Tokyo height restrictions are far more malleable so long as builders accommodate the neighboring properties’ rights to sunshine. Compare this with the effects of inflexible height restrictions in Manhattan: during the 1950s, competitive housing markets ensured that “tens of thousands of new units were built…, while prices remained flat” (Glaeser et al. 2005); however, height restrictions introduced in the 1970s meant that, “despite skyrocketing prices, the housing stock has grown less than 10 percent since 1980” (Glaeser et al. 2005). As Sowell (2011) points out, “the proportion of new housing units in buildings 20 stories and higher, which had been increasing in Manhattan from the beginning of the twentieth century until 1970, suddenly reversed and began a decades-long decline.”

There were 942,000 housing starts in Japan in 2018. In the UK, there were 194,000. In 2019, average rents in London were “upwards of £2000, while average rents in Tokyo [were] about £1,300.” The flexible housing market also means that old homes are being regularly knocked down for new homes to be built, ensuring that Tokyo’s dynamism is sustained.

In Nigeria regulations and restrictions on land and capital goods for construction had led to a housing deficit of over 17 million houses by 2015. The situation is not very different today. The 1978 Land Use Act stipulates the administration and control of all land in the country. Except land owned by the federal government, the law put all land under the control of the state governors. The governors, each under the advice of a “Land Use and Allocation Committee,” decide the use of land. Nigerians can only get access to the land by getting a certificate of occupancy (CO), which is valid for only ninety-nine years, after the governor has decided the use of that land. Housing development is slow, because if the governor has not stipulated what the use of barren land will be, it is practically impossible to get a CO and this disincentives construction. When people, to address their dire housing needs, take the law into their hands and construct homes for themselves, the governors forcefully evict them and destroy their homes.

Also, in Nigeria the importation of bagged cement, an important capital good in the construction of houses, is illegal. Cement is produced locally by a couple of companies with entrenched government connections. Hence “The government and indeed many Nigerians have almost come to accept that paying over the odds for cement is a sacrifice worth making in the name of having cement produced in the country” (Feyi Fawehinmi 2017). And just like any with other commodity, when the prices of cement are high, people will demand less.

The empirical evidence and the economic theory are perfectly consistent on this point: if you restrict how land can be used through strict zoning and planning laws, you will push up production costs and restrict supply, in turn creating housing affordability problems. This problem is not just about the cost of living, but also about inequality and social mobility. We know that most of the growing inequality in developed nations is caused by rising house prices. Inaccessible housing markets restrict job opportunities and entrench systemic inequality among groups that cannot afford to get a foothold. This problem will go away if the politicians and bureaucrats stop telling people how they can use their land. The empirical evidence and the current literature tell us that deregulated housing markets create affordable housing. We know how to solve this problem. We have for a while.

Mitchell Harvey is a newly admitted graduate student in Stanford University’s political economics PhD program. He has previously worked as a teaching associate and research assistant in the Monash University economics faculty. Tam Alex is an engineer and economist. His research interests include economic and energy development. He publishes the Nigeopolis, a magazine dedicated to advocating for the inalienable rights of Nigerians to life, liberty, and property. This article was originally featured at the Ludwig von Mises Institute and is republished with permission.