The nineteenth century marked the most dramatic leap forward in human welfare ever witnessed. It was a century defined not by aristocrats or emperors, but by coal, cotton, contracts, and capitalists. In his lectures “War, Peace, and the Industrial Revolution” and “The New World of Capitalism,” historian Ralph Raico masterfully outlined how capitalism, industrialization, and free trade shattered the stagnant feudal order and lifted hundreds of millions from abject poverty. Despite the predictable outcry from the old regime—the landed aristocracy, royal monopolists, and reactionary intellectuals—the tide of liberty proved irresistible.

Raico reminds us that classical liberalism’s victories were not abstract victories of theory, but practical triumphs. What David Landes called “the European miracle” was not divine coincidence—it was the institutional result of decentralization, secure property rights, and the growing legitimacy of commercial freedom. In Raico’s telling, it was precisely because no empire reasserted Roman-style hegemony over Europe after the Middle Ages that real progress was possible. Political fragmentation created an environment of competitive governance where entrepreneurs could flee oppressive jurisdictions and take their capital and talents elsewhere.

Industrialization did not erupt by accident. It emerged in England—where private property had already been affirmed by the Magna Carta, where Parliament restricted royal taxation, and where common law defended contractual rights. As Raico emphasizes, the rise of capitalism coincided with the decline of arbitrary power. The forces of industry and commerce were not extensions of monarchy but reactions to it. And the elites knew it.

The enemies of this new order—what Raico calls “the losers”—were the landed aristocrats and old regime rentiers who feared their privileges slipping away. Their incomes were not derived from satisfying consumer demand but from rents extracted by legal privilege: tariffs, hereditary offices, government sinecures, and protected monopolies. They saw in the smokestacks and crowded factories not opportunity, but a threat to their hierarchical control.

Desperate to maintain their grip, these elites launched what Raico identifies as a vast propaganda war against industrial capitalism. They clothed themselves in moralistic garb and pretended to speak for “the poor” even as they resisted every policy that might allow the poor to better themselves. In England, the infamous “Blue Books”—reports commissioned by the aristocratic Parliament—depicted the horrors of the industrial working class, but as Raico and economist F.A. Hayek both point out, these reports were not disinterested scholarship. They were political weapons.

Hayek, in Capitalism and the Historians, demolished the Blue Books and the historiographical tradition they spawned. He exposed them as ideologically loaded and methodologically flawed. Far from being objective assessments, they were designed to make capitalism appear monstrous by comparing idealized feudal rural life to the harsh—but improving—realities of urban industrial existence. What they ignored was that industrial labor, for all its hardships, was a voluntary alternative to starvation in the countryside. For most workers, the factory was not hell—it was a step up.

Raico underscores that real wages for British workers rose dramatically throughout the nineteenth century. Life expectancy increased. Child mortality fell. Literacy soared. The claim that workers were “wage slaves” was always rhetorical sleight-of-hand—a way to equate peaceful voluntary exchange with chattel bondage. But unlike actual slaves, workers could leave, bargain, emigrate, or start their own businesses. And many did.

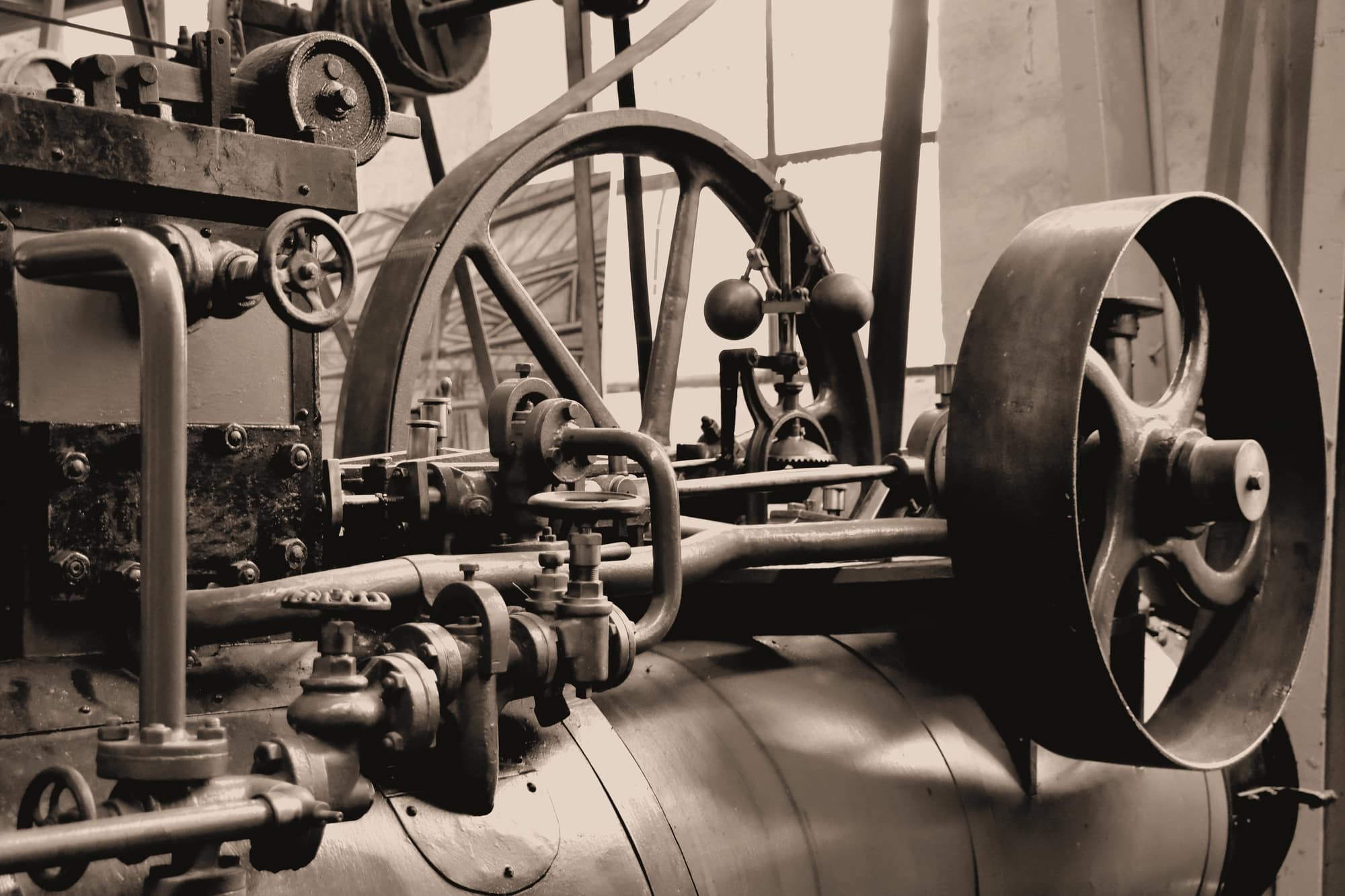

The transformation brought about by capitalism was not just economic, but moral. As Raico stresses, the capitalist order was the first social system in history that rewarded peaceful cooperation over violence. It was not the sword, but the plowshare—and later the steam engine—that advanced civilization. Free trade, too, played a revolutionary role. Under the guidance of men like Richard Cobden and John Bright, Britain repealed the Corn Laws—tariffs that enriched landlords at the expense of everyone else. This ushered in an unprecedented age of global commerce and relative peace.

Raico juxtaposes this with the behavior of the ancien régime. In pre-capitalist societies, elites sustained themselves by conquest, taxation, and plunder. The state was a predatory enterprise. In contrast, the capitalist entrepreneur must persuade consumers to part with their money. He must innovate, economize, and compete. No longer could status alone guarantee income—under capitalism, one had to serve.

But the intellectual class often failed to appreciate this. Many intellectuals, jealous of their declining influence in a society increasingly governed by merchants and manufacturers rather than theologians and monarchs, sided with the old order. Raico cites Hayek’s insight that intellectuals are particularly prone to despise capitalism because it distributes rewards in ways they cannot control. They called for protectionism, regulation, and moral “reform”—not to uplift the poor, but to reassert their authority.

The irony is that, by demonizing capitalism, they often harmed the very people they claimed to defend. The reimposition of tariffs, for example, raised food prices and stifled industry. Anti-capitalist labor laws in their early forms often banned child labor in ways that ignored household poverty—leaving children to starve or steal rather than work in improving conditions.

Capitalism, properly understood, was not the enemy of the poor. It was their escape route. As Raico passionately argues, it was through market-driven growth that humanity finally broke the Malthusian trap. For centuries, population growth had kept wages at subsistence. But with capital accumulation, technological innovation, and expanding trade, for the first time in history, productivity began to outpace population. The results were astonishing: a doubling, tripling, and quadrupling of living standards over a single century.

The old elites fought this tooth and nail—but lost. And thank God they did. The nineteenth century, for all its faults, was a monument to liberty’s power. Capitalism did not enslave mankind—it liberated it. That its enemies came wrapped in the banners of church, crown, and compassion should remind us: privilege always speaks the language of virtue when it’s threatened.