When the Rev. Jesse Jackson died this week in Chicago at age 84, the tributes were predictable. Jackson was a protégé of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., a two‑time presidential candidate, and the most prominent black civil‑rights leader for decades. The Associated Press obituary noted that he continued to speak out for the poor and underrepresented and maintained a schedule of protests and speeches until his body failed him. His family called him a “servant leader” whose crusades spanned voting rights, jobs, education, and health care. At first blush, the narrative is obvious: the Rainbow PUSH founder who marched with King, championed the oppressed and attempted to build a political “rainbow coalition.”

But Jackson’s life was not a simple morality play. Two themes defined his half‑century in the public arena: a principled opposition to overseas war and an equally stubborn devotion to hard‑left domestic policies that turned the free market into an enemy. In death, the man deserves credit for his peace advocacy—but his domestic record cannot be ignored.

Jackson didn’t just march against wars; he ran for president to reshape his party from within. Before his first bid, he helped add roughly two million black voters to the rolls, then built a “rainbow” of activists—progressives, labor unions, minorities, and anti‑war groups—to back him. He used this bloc to demand a “People’s Platform” that insisted on higher corporate taxes, single‑payer healthcare, and wage controls. Even some black leaders dismissed him as a fringe figure, but he leveraged that base to force the Democratic party to adjust delegate rules.

In 1984 Jackson commanded about 18% of the primary vote and led in more than thirty districts with heavy black majorities. His convention speech demanded fair districts and blasted “second primaries,” and he warned Democrats that black voters could “win without the party”—but that the party could not win without them. His first run proved he could translate protest into votes, but it also showed he would use electoral clout to push ever‑bigger government.

By 1988, more black politicians supported him and the field lacked a clear front‑runner. He professionalized his campaign and broadened his base to farmers and rural whites. Strategists noted that with a divided white vote he could win Southern states with just 20-30% support. He went on to win primaries in thirteen states, forcing Democrats to replace winner‑take‑all contests with proportional delegate allocation. Although party leaders ultimately backed Massachusetts Governor Michael Dukakis, Jackson’s campaigns showed how a multiracial coalition could compel concessions. His strategy would inspire future Democrats like Barack Obama—and cement the identity‑based alliance that today dominates the party.

Few civil‑rights leaders were as consistent in questioning U.S. intervention abroad. In the 1980s Jackson helped revive the anti‑war movement, urging a shift from “military interventionism, nuclear brinkmanship and Cold War posturing” toward diplomacy and reductions in Pentagon spending. Campaigning for the Democratic nomination in 1984, he described the CIA’s clandestine campaign against Nicaragua as an “undeclared war against the people of Nicaragua…[that] must be stopped.” This was not fashionable rhetoric in the era of Ronald Reagan; it was a serious critique of covert wars being waged in the name of anti-communism.

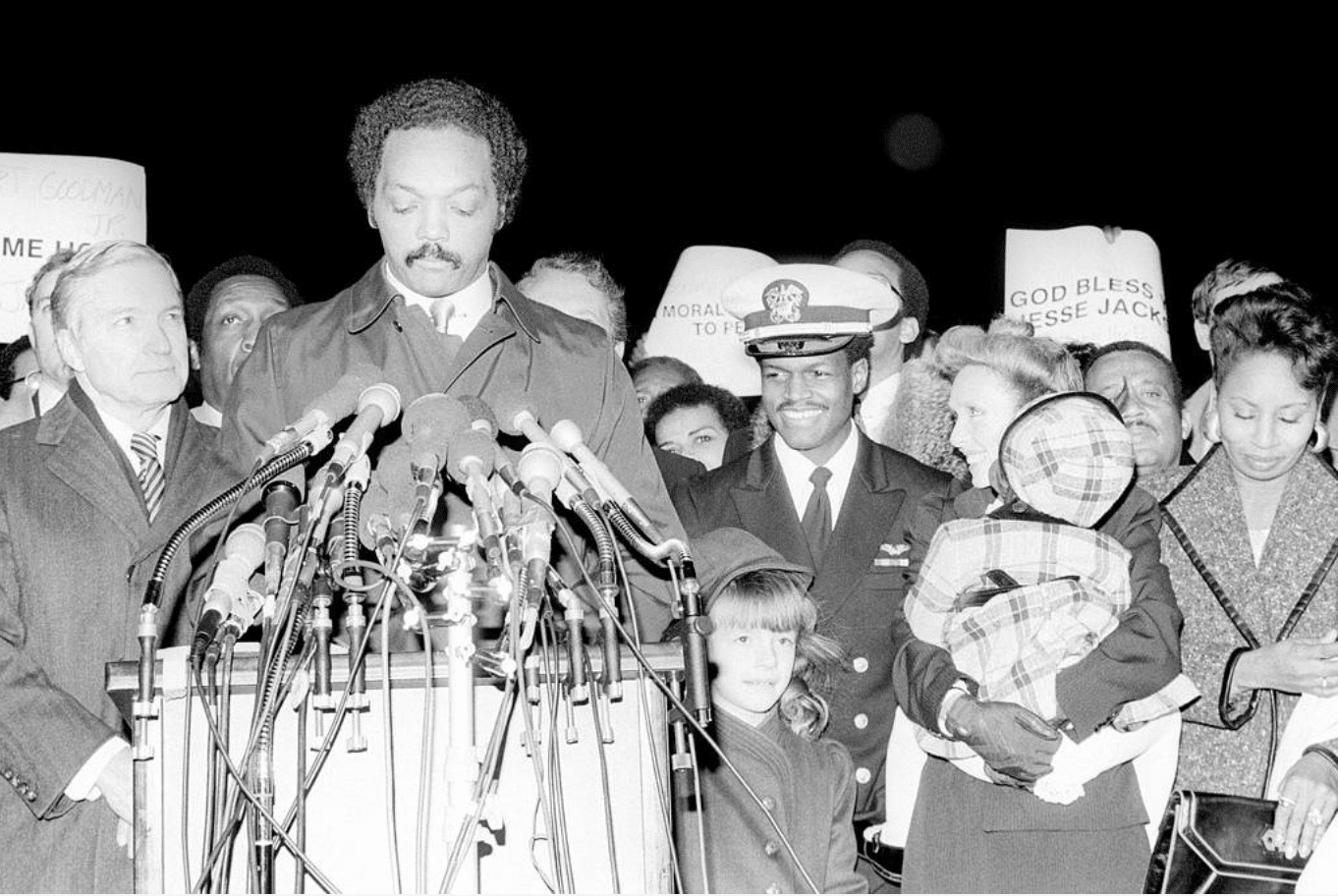

Jackson also put himself on the line for hostages. In 1990, as Saddam Hussein held American civilians in Iraq in the run-up to the Gulf War, Jackson asked diplomats how he could help. The U.S. chargé in Baghdad later recalled that they told him to get the hostages released; Jackson travelled to Baghdad, met Iraqi officials, and returned with several freed hostages. He repeated such missions in Cuba and Syria, seeing hostage release as a way to avoid escalation. When he met Yasser Arafat in 1979 he hoped to broker ties between the Palestine Liberation Organization and Washington.

Perhaps his most public anti‑war moment came on the eve of the 2003 Iraq invasion. At a large Washington protest, Jackson told a crowd that “we need a regime change in this country” and argued that a pre‑emptive strike would cause the United States to “lose all moral authority.” He said killing innocent people to depose Saddam Hussein would be “amoral.”

His antiwar rhetoric even extended to Israel. During his 1984 campaign he endorsed a Palestinian state and questioned U.S. military aid to Israel, arguing that Israeli weapons were used to maintain apartheid in South Africa. Those positions alienated pro‑Israel interests, but they were part of a consistent non‑interventionist vision. Late in life, as Israel’s war on Gaza raged, Jackson appeared before the Chicago City Council to support a cease‑fire resolution—a rare act for an aging civil‑rights leader.

Whatever one thinks of his politics, Jackson deserves credit for consistently opposing unnecessary wars. In a country where presidents from both parties have embraced military adventurism, he insisted on dialogue over bombs and risked political capital to rescue hostages. That record is worth honoring.

Jackson’s domestic agenda, however, reflected a very different ethical compass. In the 1980s he argued that the U.S. economy was rigged and that only massive federal intervention could correct it. He pushed for government‑run single‑payer health care, boasting that a national healthcare system would put “medical spending decisions under federal control.” He demanded a new federal investment bank financed with taxpayer‑insured pension funds to direct capital to preferred projects. He advocated raising the minimum wage, imposing “comparable worth” regulations and forcing equal pay across occupations. Few Democratic candidates dared to champion such sweeping central planning; in 1987 The New York Times described him as “the most unabashed advocate of increased government spending.”

In 1988 Jackson offered a detailed blueprint. He lamented that half of new jobs paid less than $7,400 a year and argued that welfare recipients had no incentive to work. His answer was not deregulation and tax relief but bigger government: raising the minimum wage, introducing “family allowances” to supplement earnings, and establishing a $5‑10 billion federally funded childcare program. He urged doubling the federal education budget to about $40 billion annually and increasing teacher pay. For health care, he proposed a universal system guaranteeing “cradle‑to‑the‑grave” coverage, with private institutions contracting with the government and the government essentially setting the rules.

His tax proposals were equally radical. Jackson called for a $40 billion annual tax hike and higher corporate and personal income taxes on high earners. He supported tariffs and penalties against multinational corporations that moved production overseas, explicitly opposing free trade. He wanted a higher minimum wage, pay‑equity regulations, and a large expansion of public employment. In short, his program resembled the economic platforms of European socialists, not the American tradition of limited government and individual enterprise.

Free‑market economists criticized these plans for ignoring incentives and punishing productivity. Raising wages by government fiat reduces employment for the very workers the policy aims to help, while universal health care financed through higher taxes crowds out private investment. A government‑run investment bank invites political misallocation of resources. And tariffs on overseas production amount to hidden taxes on American consumers. Jackson’s policies would have replaced voluntary exchange with bureaucratic edicts and shifted wealth from those who earn it to those who lobby for it.

Jackson did not merely advocate socialist policies; he sought to compel private firms to implement them. His tactic was corporate confrontation. In 1982, as head of Operation PUSH, Jackson called for a boycott of Anheuser‑Busch. He demanded that the brewer release detailed employment and financial records on black participation and insisted that black businessmen donate $500 to his organization to demonstrate their commitment. Local newspapers accused him of threatening to stop trading with Budweiser unless the company met his demands. The boycott ended only after Anheuser‑Busch reached an agreement with Jackson, raising questions about whether social justice, or political leverage, was the real objective.

This pattern repeated across industries. During the 1990s and early 2000s Jackson targeted technology companies for lacking diversity. He would purchase a handful of shares, show up at shareholder meetings and denounce “all‑white” leadership teams. After such protests, companies often “end up buying him off with donations and contracts.” Jackson was accused of exploiting corporate executives who feared being branded racist and described his activism as a “shakedown.” Whether one agrees with the tone, the observation that businesses responded by writing checks to Rainbow PUSH underscores the transactional nature of Jackson’s activism.

Jackson’s pressure campaigns were not limited to corporate boardrooms. When he ran for president in 1984 and 1988, he used racial politics as a wedge. He described economic disparities as evidence of systemic racism and argued that only a “rainbow coalition” of minorities and liberal whites could fix them. Critics said his rhetoric inflamed racial tensions and cast markets as oppressive instruments of white supremacy. A socialist like Jackson would never admit that markets are color‑blind; they reward productivity, not race. By demanding racial quotas and government redistribution, Jackson undermined the principle of voluntary cooperation and turned politics into a zero‑sum struggle.

Perhaps the most damaging episode in Jackson’s career was his handling of relations with American Jews. During his 1984 campaign he referred privately to New York City as “Hymietown,” using a slur for Jews. When the remark became public, he first denied making it and then apologized, telling a synagogue audience that “it’s human to err, divine to forgive.” The apology was undercut by his refusal to repudiate Nation of Islam leader Louis Farrakhan, who had introduced him at a rally and later called Judaism a “gutter religion”; Jackson’s campaign denounced the comment but not Farrakhan. The Jewish Telegraphic Agency noted that these actions created a lasting chill with American Jews, who had been allies of the civil‑rights movement.

Even some of Jackson’s long‑time allies expressed unease at what looked like self‑serving activism. Business executives quietly complained that Rainbow PUSH’s campaigns ended after they wrote checks. Economists pointed out that his economic proposals would entrench dependency rather than foster opportunity. And many civil‑rights veterans were uncomfortable with his closeness to Farrakhan and his willingness to blur lines between advocacy and extortion.

It would be simplistic to dismiss Jesse Jackson as either hero or charlatan. His anti‑war activism deserves recognition; he stood against imperialism when both parties embraced it, risked his reputation to negotiate hostage releases, and pressed for diplomatic solutions to conflicts. That record puts him in the company of those who believe that the United States should mind its own business abroad, a view that is now gaining traction across the political spectrum.

Yet his domestic agenda represented a war against the market and, by extension, the people who depend on it. Jackson’s calls for universal health care, massive tax increases, protectionist trade barriers and racial quotas were rooted in a belief that government coercion can engineer fairness. Americans should reject that premise. Voluntary exchange and property rights are the surest paths to prosperity and state interference breeds corruption, privilege, and division. Jackson’s corporate “shakedowns,” nepotistic politics, and racial baiting illustrate those dangers.

As America reflects on Jesse Jackson’s life, it should embrace the part of his legacy that championed peace abroad. At the same time, it must learn from the failures of his war at home: the misguided belief that freedom can be purchased with other people’s money, that corporate coercion yields justice, and that identity politics is a substitute for individual rights. Requiescat in pace—and may future leaders pursue peace without waging war on liberty.