The Washington Naval Treaty is usually treated, when mentioned at all by historians, as an unmitigated failure, but—although he says this in the most pianissimo tones—I think John Jordan’s Warships After Washington: The Development of the Five Major Fleets, 1922-1930 makes a strong case that in achieving its limited ambitions the treaty was very effective, and actually served the goals of all the contracting powers fairly well.

The treaty, generally, is regarded as a failure because World War II happened. That’s rather a great burden to place on an agreement which mostly deals with the technicalities of ship tonnages and armaments. (The actual treaty is included in the book as an appendix; it’s a fairly neat example of concision and clarity in a government document.) But the Five Power Treaty (as the main and most famous Washington Treaty was technically known) was not the later Kellogg-Briand, which outlawed war as an instrument of national policy, nor was it entered into out of pure idealism. The Washington Naval Treaty was designed in the way any agreement ought to be: it had a specific goal, the limitation of capital ship construction by the five major powers to certain total tonnages, a specific set of rules about how that goal was to measured, and a limited time period after which the agreement could be renegotiated. (The treaty was to expire in 1930, leading to the London Naval Conference and the less-successful London Naval Treaty.)

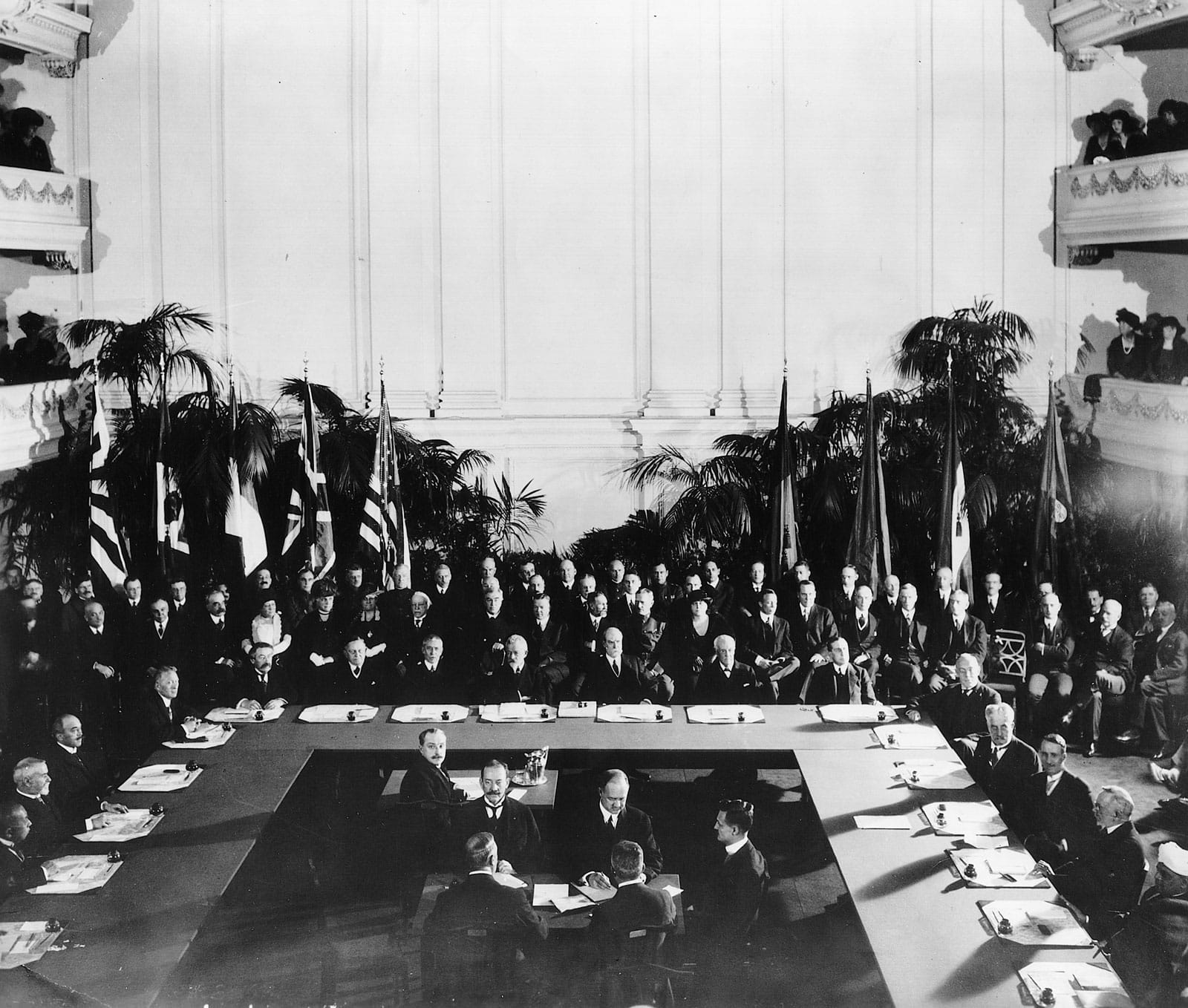

I was somewhat disappointed with Jordan’s discussion of the actual negotiations which led to the treaty, which featured an American delegation including Charles Evans Hughes, Henry Cabot Lodge, and Elihu Root. The other delegations were somewhat less star-studded, but the British did send Arthur Balfour, who had also been integral to the Versailles negotiations. It helped the Americans that the negotiations were being conducted a short walk from the Capitol, and were also notable for the American use of cryptography to break Japanese diplomatic codes during the talks; the Americans were able to form a pretty accurate impression of the minimum Japan would accept, and were thus able to hold them to it. The revelation of this espionage by Herbert Yardley, one of the main cryptographers, in his 1931 book The American Black Chamber, was a cause of tremendous upset to the Japanese (where his book was something of a bestseller) both because of the revelations and because (according to Rear Admiral Edwin Layton in his book And I Was There) the Japanese ambassador had paid him $7,000 for the same information the year before on the promise that he would keep it secret. Regardless, Jordan doesn’t dwell on the politics of the treaty, but focuses more on the actual effects on naval construction during the 1920s.

It’s impossible to discuss the treaty itself without considering the state of all of the contracting powers in 1921. In short, they were in poor shape. Britain had the largest fleet afloat, but increasingly her fiscal capacity (to say nothing of her will to pay for guns over butter) was sapped. Moreover, the naval developments of the war years had demonstrated that much of her fleet would soon be out of date. In some ways, the political winds had turned against her too. While she had eliminated Germany’s fleet as a threat to the Home Islands, further afield trouble loomed: the Entente Cordiale was fraying as France attempted to pursue a more aggressive anti-German policy in the aftermath of Versailles, Italy was unhappy with her share of the spoils in the postwar settlement, and the Anglo-Japanese alliance was breaking down (some argued it was already beyond repair). These developments meant that the relative friendliness of the major powers in the Mediterranean and the Pacific could no longer be counted on, making the kind of concentration of the whole British fleet in home waters as had been done during the war no longer possible.

For the French, the story was far worse; the industrial regions of the north had been devastated. If the fleet had been neglected pre-war, it was entirely forgotten during the existential struggles of 1914-1918. As Jones writes, “France…entered the Washington Conference with the worst possible negotiating hand.” In some ways this actually helped France during the negotiations—since none of the three main powers regarded them as a major participant, nor were they regarded as a threat. Italy was, on the other hand, on the upswing, with a new program of modern construction and an increasing qualitative superiority to the French, especially in smaller fleet units.

Finally, Japan and the United States, who were seen as the “protagonists” of the treaty (and not only in hindsight), both emerged from the war with stronger navies and enhanced international standing, yet each was also facing fiscal constraints and great uncertainty about their future international role. The United States had begun an ambitious naval construction program in 1916, under which Congress had committed to build ten new battleships and six new battlecruisers in order to fully-modernize the U.S. Navy (USN); many of these were already in various stages of construction when the conference began. (France, on the other hand, had no capital ships under construction.) Japan was also moving towards an ambitious “eight-eight” fleet of eight battleships and eight battlecruisers in order to counter the USN and Royal Navy (RN). In spite of this, both Congress and the Imperial Diet were questioning the need for these ambitious commitments, made in wartime, now that peace was settling over the world again.

The conference was convened not just in the spirit of utopian idealism (Lodge, one of the main sponsors, had killed American ratification of the League Covenant because he thought it too utopian) but as much if not more in the spirit of fiscal pragmatism. Everyone wanted to reduce arms expenditures, but nobody wanted to do it at the risk of their security. The treaty is most famous for the agreed 5:5:3 ratio in capital ships between Britain, the United States, and Japan. This is a bit misleading, since it was in fact a 5:5:3:1.75:1.75 ratio in capital ship tonnage between all five powers, with Italy and France being held to parity with one another. The idea, at bottom, was that no power would be able to build a fleet which could certainly crush any other power’s fleet, although the powers with greater international maritime obligations (the United States and Britain being two-ocean powers and Japan being an island nation) were to have somewhat more than the others.

There was something in here for everyone to resent: the Japanese were most notably unhappy with their ratio, since they believed they needed at least 70% of the USN’s tonnage in capital ships in order to successfully defeat the United States in a naval conflict. The divisions over the ratio would split the Japanese naval brass into two groups: the Treaty Faction, who believed that the 60% ratio was the best Japan could reasonably expect, and that a naval arms race with the United States or Britain would be doomed, and the Fleet Faction who believed that Japan ought to renounce the treaties and start building/ As a smarter man than I said of this division, “I’m increasingly coming round to believe the main difference between the two factions was an ability to count and engage with reality, if you couldn’t do either you were Fleet Faction.” But the French resented being held to parity with arriviste Italians, as well as the treaty’s non-recognition of its status as a major colonial power with obligations in Africa and the Pacific. The Italians, for their part, found the restrictions on new construction somewhat galling, especially as many of their capital ships were proven to be out of date by the events of the war.

For the British, the treaty didn’t go far enough; despite their lead in submarine technology, they had initially hoped to get the submarine banned as a weapon of war (they would try again in London in 1930—interestingly enough, in both cases France would lead the charge against the proposal), as well as to place tonnage limits on all categories of units, not just capital ships. In essence, the British had desired to use the treaty to uphold the Two Power Standard, the erstwhile naval maxim that the Royal Navy should be able to defeat the two next largest fleets in the world combined. The United States made the fewest concessions (somewhat oddly, given that Congress would be reluctant at best to fund further naval expansion until the Two Ocean Navy Act of 1940), with the most historically-notable one being that the United States would not build any more fortifications in the Pacific west of Hawaii, including in the Philippines.

But the proof of the pudding is in the eating and the proof of an agreement is in how closely it is hewn to. Most discussions of the naval treaties (correctly) assert that all the powers cheated on their tonnage limits, especially on the cap of 10,000 tons for cruisers. Jordan devotes much discussion to how difficult every power found it to build a truly balanced warship weighing 10,000 tons a number, which was settled on (as far as I can tell) because it’s a pleasantly round one and was a little bigger than most of the cruisers the powers had already built. The cheating, as I said, was real enough, although much of it was more of a legalistic bending of the rules than an outright defiant breaking of them. (There’s a convincing argument that at least part of the reason the Japanese cruisers ended up so grossly overweight was that the Japanese were bad at calculating their ships’ true tonnage; they still would have cheated, but they believed they were cheating by less than they actually were.) Regardless, the major restrictions of the treaty were essentially upheld throughout its life; no power built more capital ships than it had been allotted (indeed, the United States never built up to its quota) and while cruisers were built not in strict conformance with the stated rules respecting displacement, no power fielded an obviously superior and non-compliant class of ship which menaced the balance of power as contemplated in the treaty.

Jordan offers a plethora of interesting insights into how the treaty affected naval design and thinking during its ten year life, and if you have any interest in the development of seapower, it’s a worthwhile read for the technological innovation on display. From the perspective of a non-naval engineer, what really stands out to me is the degree to which the entire enterprise seems to have been unfairly maligned. The traditional picture of the naval treaty era is one of gleeful building of grossly noncompliant warships by the scheming Italian fascists and Japanese militarists, while the indolent democracies slumbered ignorantly. A more unfair characterization of the decade is hard to imagine; while the treaty did not totally prevent jockeying for position in the world of naval affairs, all nations avoided a ruinously costly arms race while maintaining fleets which at least guaranteed they could not be attacked by any other power with impunity.

What is most striking is how favorable the treaty was to Japan; the Americans essentially conceded their forward bases (Guam, Wake, the Philippines) from which they might have been more effectively able to strike at Japan, in exchange for a pretty paltry 5:3 superiority in capital ship numbers, one which wasn’t actually achieved during the era of the naval treaties anyway due to congressional lassitude on naval funding. All this in spite of the fact that the Americans were reading Japan’s mail! The sense of national humiliation on the part of the Japanese as a result of the treaty, and the resultant lasting sense that the civilian government had betrayed the nation, helped fuel terrorism by junior naval officers in the years after the treaty was ratified, a result which feels even more perverse when one considers the relatively good deal the Japanese got. But in some sense the Japanese militarists were just ahead of the curve.

It has been the very unfair fate of the Five Power Treaty to be consistently damned as ineffective or worse by people who failed to understand its goals or to actually measure its results. It deserves modestly better: the diplomats in Washington negotiated an agreement which achieved what they had set out to achieve. That it failed to prevent World War II was no more their fault than World War I was the fault of the 1865 International Telegraphic Convention.