“Official Truths are often powerful illusions.”- John Pilger

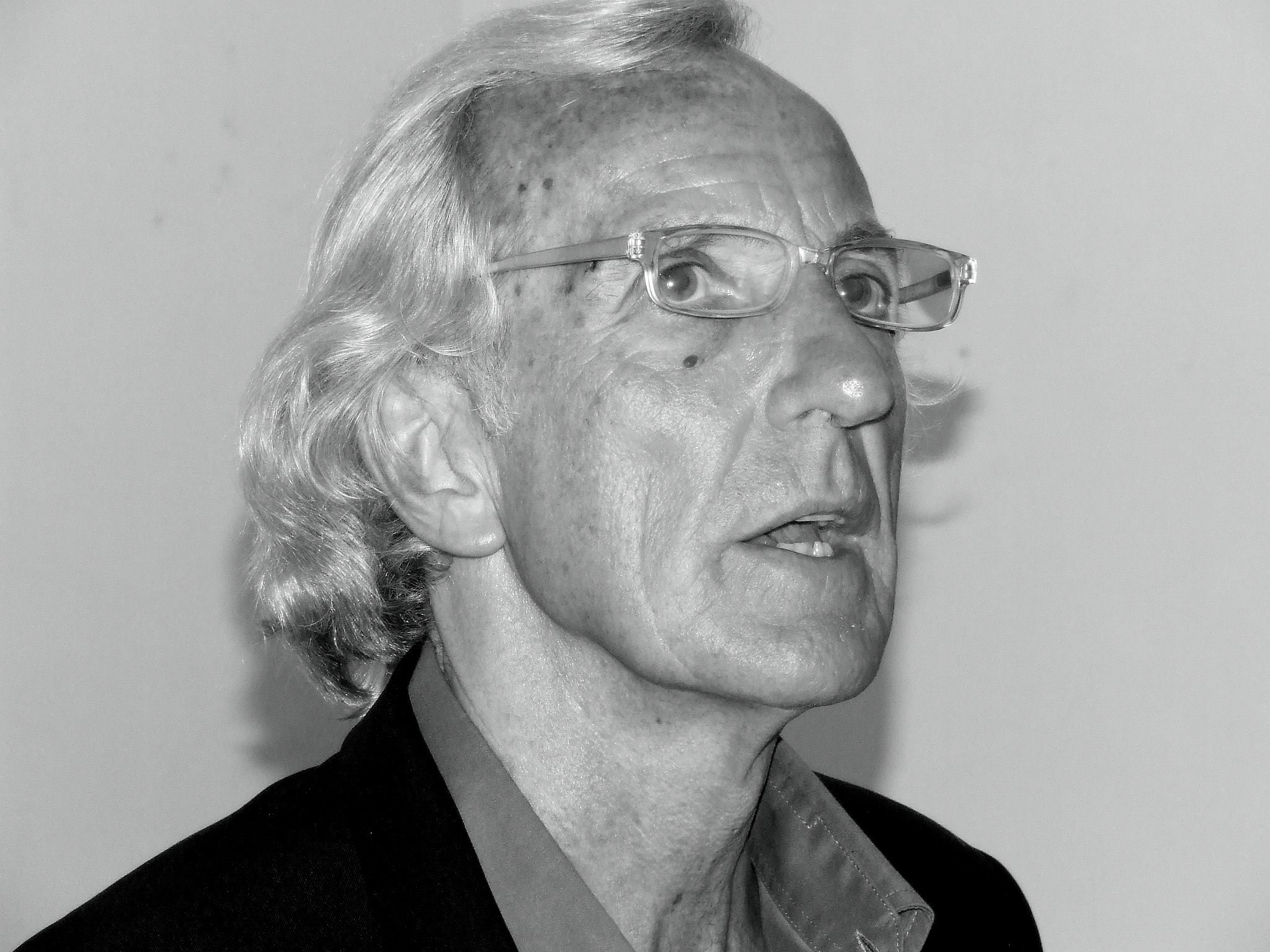

For most of his life, John Pilger spoke out against power and championed those who get lost in the shadows of history. The Australian-born journalist (though truly a citizen of the world) passed away in December at the age of 84. It was a tragic loss. Pilger worked for some of the more famed media outlets, from Reuters to the Daily Mirror, though he always kept his own unique voice when reporting and witnessing events. It was during the Vietnam War that his dissident words ascended among his peers, with a film making style and integrity that put shame on the powerful while humanizing their victims—victims that are often relegated to the dustbin of history, at best statistics in the ledger of other’s greatness. John Pilger always saw them as people, as human beings that mattered.

Writing numerous books and making several documentaries, he would often attack Western foreign policy, criticizing wars and the exploitation occurring in the developing world. It was with his compassion and focus on the conquered peoples, such as Indigenous Australians, that Pilger was especially adept. For all his life, he was tireless and relentless in his expression against war crimes, imperialism, and corruption. Despite the countless words he typed out on heavy subjects, every injustice he witnessed, and the overbearing nature of it all, he never deteriorated into cynicism or lost sight. With his words he unveiled a compassion and a dignity for people who, despite their hardship, retained the human spirit.

When narrating or giving an interview, he could sound calm and soothing, but he would not shy away from argument when required. Take for example his 2003 interview with Kim Hill. Pilger’s anti-war position was challenged by the pro-agenda Hill, who believed the coming war with Iraq was inevitable, a necessity, and a good thing. The establishment and its many media cheerleaders lusted for the destruction of Iraq and perhaps even the whole Middle East. In the interview Pilger pushed back on the claims that the invasion would be another, “just war.” They are always “just wars” until the generation that fought them grow weary and suddenly they become regretful mistakes.

He was always consistent, a man of the left in the traditional sense even while others meandered. For John Pilger, loyalty remained to principles of justice, and to those who were often without voice, were ignored, or crushed beneath power. The people of the Chagosian archipelago for example, who had their home islands stripped away and were forced to become refugees because the British Empire in its twilight decided to “nationalize” and possess that which did not belong to them. Illegal even under the laws of the Crown, yet with silence from outsiders, the people of the Chagos islands were dispossessed so that Britain and now the United States may have another military base, an anchored platform used for the many wars of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. Colonialism adjusted itself and adopted the language of the international order, but Pilger saw it for what it was.

“History is hosed down with official denials. Of course they are worthless unless they are subjected to scrutiny. Journalism is not about accepting the glib assurances of politicians and intelligence bosses.” John Pilger wrote that in his book, A Secret Nation, covering the coup of Gough Whitlam, the sitting Australian prime minister who was over thrown by the governor general and replaced by the opposition leader. It was a coup that had American and British government finger prints over it, an event in Australian history swirling in controversy but soothed acceptance. The Constitutional Crisis, as it’s known locally, was certainly a coup by any other name. Journalists like Pilger continued to report and unveil the nefarious nature of the coup, even as the public went back to their beers or forgot when a prime minister was overthrown.

Pilger understood the nature of power and government. Big business and individuals will would turn the other way or knowingly work with warlords and governments actively committing human rights violations or even war crimes as long as money was to be made. Pilger was often complicated and nuanced in his revelations of corruption and the abuse of power, and he did not omit facts out of ideological bias. A communist, fascist, or liberal democratic regime was fair game for his condemnation so long as they abused power and hurt the innocent. That is the anarchist indictment on government that hides among the pages of Pilger’s writing. Though he was always looking for the angels to fix the process, to obey the law and to correct the injustice, there is among his many examples of terrible power an understanding that absolute authority or the monopoly itself is the problem.

Often a champion for labor rights, the worker, and a “fair go,” Pilger had the instincts of a good “lefty,” especially one from his era when the union was supposed to represent the worker and their families. He thought that “free” healthcare, education, and public services must be base requirements for a society that protects the most vulnerable, to “uplift” them so that they may transcend poverty. As Pilger puts it in Distant Voices, “Poverty kills.” Not above criticizing sacred institutions such as the British National Health Service, he would reveal its dangerous neglect and inefficiencies, though with the angle of reforming what he believed could be a beautiful thing. He did not share the libertarian realization that monopoly is flawed and corrupt each and every time, but his words could dangle close to an “if only” embrace. Ever tireless and empathetic to those who suffer, who are at risk and who are lost beneath the weight of such powerful creatures, Pilger’s key strokes are were sword and his wit the shield for those who have few champions.

Up until his last breath, Pilger was questioning the menace of propaganda in the war between Russia and Ukraine, and challenging the “accepted” narrative that Moscow is by default evil. His documentary The Coming War with China warns of a new cold war and the simmering risk of an all out conflict between the West and East. The ever present humanitarian tragedy in Gaza was always a concern for him, especially in the weeks before his passing. Always a supporter of free speech and government transparency, he had been an advocate for the release of Julian Assange, embracing Wikileaks and his fellow Aussie from the moment both became household names. With a passionate mind for justice, he also held a historian’s memory, understanding that the past is a precious clue as to why we are here and where things may lead. Such knowledge and wisdom are reflected in his writings and speeches, and those of us who read and heard him are better for it.

John Pilger once recalled, “I grew up in Sydney in a very political household, where we were all for the underdog.” Though he did move from Sydney, that upbringing of discourse and a sense of right and wrong never seems to have left him. Every step of the way, he was defined by a career that advocated for the underdog, never letting that a career separate him from his principles and sense of justice.

In December the world lost a champion. Thankfully John Pilger never was silent, and leaves a body of work that will echo deep into the future. With tenacity and dignity he has gone on to inspire others to speak and write with a courage that he forged in an age when cowardice is profitable and mercenary obedience to power so common. John Pilger and those he inspired are the heroes against power. Though he never fired a bullet in anger, his typewriter and keyboard kept punching on. Rest now Mr. Pilger; the world thanks you.