Last month the DC hawks’ favorite think tank, the Atlantic Council, released their long anticipated study “Sanctioning China in a Taiwan Crisis: Scenarios and Risks.” Produced in collaboration with the Rhodium Group, the final product is a highly detailed forty page analysis, informed not only by theoretical considerations but significant time spent by the authors talking with policymakers in G7 governments. Broken up into sections respectively devoted to detailing the different range of sanctions available, their probable impacts, and the hypothetical challenges to their implementation, the study is worth examining and quoting at some length.

The authors begin by asserting that, due in large part to “China’s increased use of military and economic tools to put pressure on Taiwan, Beijing’s draconian handling of Hong Kong, and evolving Taiwanese perspectives on their national identity and relationship with the mainland,” in their opinion the “long-standing guardrails around the China-Taiwan status quo have weakened.” (Page 3) And that, as a result, “Policymakers in G7 capitals are increasingly discussing Taiwan crisis scenarios, and starting to explore the range of options available to them in responding to Chinese actions against Taiwan, both beyond and below the level of invasion.” (Page 32)

Setting aside any degree of responsibility that should be accorded to Washington for its role in these negative developments—a possibility the authors obviously ignore—there is much to this. On the one hand, as its capabilities have grown, Beijing has begun asserting its hard power, economic and kinetic, in its disagreements with its neighbors (Australia 2018-present, India 2020-21, et cetera); further, Beijing did deal harshly with Hong Kong (2019-20), and particularly among Taiwan’s Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) voters there is a desire to revisit the agreements made decades ago regarding the “One China Policy.” While on the other hand, Washington’s use of sanctions has grown over the years, its foreign policy increasingly reliant on what scholar Nicholas Mulder rightly calls the “economic weapon” (as opposed to such euphemisms as “economic statecraft” or “tools,” which the authors at the Atlantic Council prefer). And despite the cautionary words increasingly coming from within the foreign policy elite itself, warning that sanctions are actually harming U.S. and Western interests, the Atlantic Council report unsurprisingly advises staying true to form in dealing with China.

Before diving into the nuts and bolts of what the Atlantic Council propose, a few further considerations are in order.

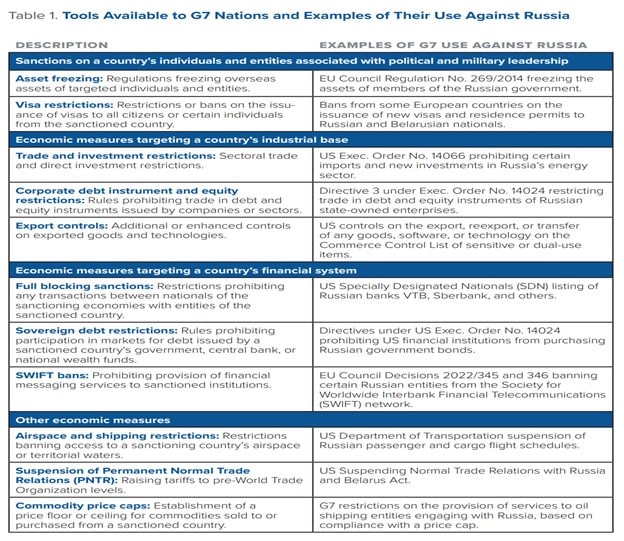

First, the authors make numerous comparisons between Russia/Ukraine and China/Taiwan. Included at the end of this article, for example, is a table taken directly from the study laying out what the authors view as a set of sanctions approximately analogous to those imposed on Russia for its repeated violations of Ukraine’s sovereignty (2014-present). But China is not Russia; for one thing its economy is ten times the size of Russia’s; for another, China is a central pillar, if not the central pillar, in world trade today. And while the authors do acknowledge this reality, as will be shown it does not show through much in their recommendations.

Second, sanctions have multiple purposes, and there are multiple types. Signaling, deterrence, and degradation number among the primary functions of sanctions, while individuals, economic sectors, or certain products can serve as the target of a sanctions regime. These can vary in intensity and scope, while the purpose and nature of sanctions can be altered as a situation develops (such as in Ukraine, where the authors write the purpose changed from deterrence to degradation). In their report the authors present sanctions packages whose intent varies, from signaling to deterrence to preemptive degradation, and are aimed with varying scope and intensity at either China’s financial sector, industrial base, or high-level individuals in the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and People’s Liberation Army (PLA).

Lastly, for all the work put into designing such sanctions regimes, the authors quietly note the obvious: whatever else they may try, “absent military intervention from the United States and allies, Taiwan is unlikely to withstand a full-scale invasion for the length of time necessary for sanctions alone to meaningfully degrade China’s military capacity.” (Page 5)

All that in mind, let’s dive in—starting with the simplest case, that of sanctions against individuals. Sanctions against individuals would be the easiest to put in place and have the lowest cost; indeed, the authors note that various Chinese officials, such as Chen Quanguo and Zhu Hailun (both CCP Politburo members), have already been placed under some sanctions, ranging from travel restrictions to asset freezes. Such limited sanctions do not and likely would not seriously disrupt trade and, as seen in the case of expropriating Russian assets, can be coordinated and executed fairly easily (at least among members of the G7). However, as the authors note, these sanctions are unlikely to accomplish much of anything beyond signaling displeasure with Beijing’s behavior for the simple fact that high level political leaders who might be targeted are likely to be aligned with Xi regarding Taiwan policy. (Page 21)

Next come sanctions aimed at China’s industrial base. Here the costs of even a narrowly targeted sanctions package have costs that add up quickly. As the authors write, “Our findings point to significant economic risks from a broad sanctions package, as well as deep interdependencies between China and G7 economies in potentially targeted sectors.” (Page 23) So interconnected are the global supply chains with China and Taiwan that even the accidental long-term disruption of TSMC’s activities would cost somewhere north of $500 billion annually (or fully half a percent of global GDP). Because of this inherent danger to G7 economies, as well as to the rest of the world, Washington and its partners will, in the opinion of the authors, be forced to rely on a narrower set of industrial sector sanctions targeting specific companies, most likely ones with ties to the PLA. Ideally, they note, sanctions could be applied in a sector where the West enjoys an asymmetric advantage in terms of trade, such as China’s aerospace industry. (Page 28) There, Chinese exports feature minimally or at least less significantly than its G7 imports. Though even these would cost G7 producers tens of billions in lost revenue, they are more likely to be enacted than others because wider sanctions would be difficult to coordinate with countries like Germany, France, or South Korea and “Could in fact strengthen support for the government [in Beijing] rather than undermine it” by threatening millions of jobs in industries heavily reliant on trade with the West. (Page 27)

Lastly are sanctions aimed at China’s financial system. Much like the limited individual or limited industrial sector sanctions packages outlined above, the authors admit at the outset that limited financial sanctions wouldn’t go much beyond signaling Washington’s displeasure. However, for all that a broad based sanctions package would cost the globe—somewhere slightly above two percent of world GDP annually by the authors’ own estimates—deep and wide-ranging financial sanctions could have results even worse:

“The imposition of broad-based financial sanctions on Chinese banks would create significant dislocations within the global financial system and would likely require a coordinated policy response among developed market central banks in order to manage the fallout…consequences could include a tightening of global trade financing conditions; weakness in emerging market currencies and balance of payments problems in emerging markets; major supply chain disruptions and interruptions to global manufacturing of consumer goods; and inflationary short-term impacts from interrupted China-world trade.” (Page 14)

Particularly at a time when emerging markets are already under the most pressure in decades, such additional pressure could prompt multiple failures and could be what ultimately detonates the global debt bomb that has accumulated over the past fifteen years. In addition to the threat of the central banks of the developed world being given the green light to continue running amuck, the authors believe that because “Even limited economic countermeasures against China would have global economic spillovers. This means any sanctions program would likely need to be paired with measures to support industries at home as well as third countries affected by lost trade and investment with China.” (Page 31) In short, carte blanche is to be given to the government writ large to intervene as it sees fit.

Combined with the possibility that “China may scale up [its] alternative currency and financial settlement systems” as a result of Washinton’s aggression, the dangers to the world economy, and the fact that China’s terms of trade would probably improve along with a weaker exchange rate, mean the authors are skeptical of both the feasibility and efficacy of broad based financial sanctions.

Besides, or rather inextricably interconnected to, the probable cost of a given sanctions package, is the feasibility of getting other governments to sign on to Washington’s preferred policy. The so-called “coordination problem” features prominently, the authors early on noting that a willingness to sanction China over Taiwan remains a “minority” position among even its G7 allies (Page 4); further, as the case of Russia has shown, outright “trading with the enemy” has been occurring, as has cheating or “evasion.” Further complicating the analysis is the uncertainty regarding the nature of a future crisis between Taipei and Beijing: with much activity taking place in the “gray zone,” G7-planners express unwillingness to go along if it appears the U.S. and Taiwan have provoked the crisis.

In conclusion, being a product of the Atlantic Council (essentially NATO’s own think tank), mistaken assumptions abound. And where the analysis is level-headed the authors are forced to admit that doable sanctions will have little to no impact, sanctions strong enough to make any difference are likely to have globally ruinous effects, and that to save Taiwan the United States would have to intervene directly anyway.