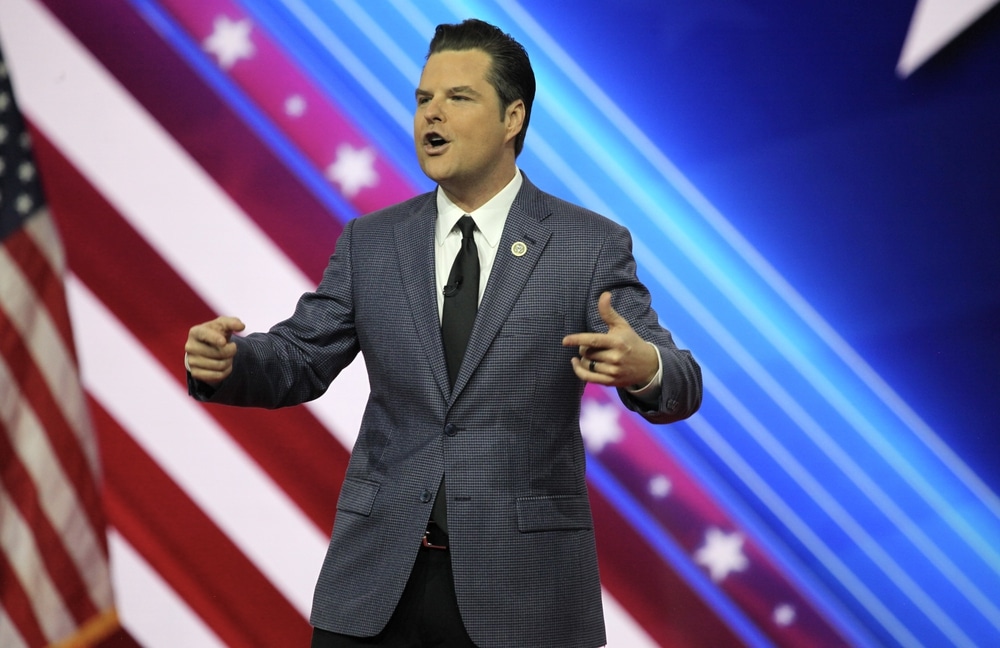

On Tuesday, Representative Kevin McCarthy (R-CA) was ousted as Speaker of the House. This came days after the former Speaker struck a forty-five-day spending deal with House Democrats to keep the government funded. The last-minute deal and successful motion to vacate are the latest acts in a weeks-long showdown between the former Speaker and Representative Matt Gaetz (R-FL).

The origin of this Gaetz-McCarthy showdown is a concession McCarthy and his allies made back in January to shore up the votes McCarthy needed to become House Speaker. According to CNN, the bloc agreed to “move 12 appropriations bills individually.” This was a major concession.

Traditionally, Congress would consider discretionary federal spending items on an issue-by-issue basis and then “appropriate” the funds for them. Under this system, the number of appropriations bills passed has to be equal to the number of subcommittees within the House and Senate Appropriations Committees. For more than a decade, that number has stood at twelve. Because of the 1974 Congressional Budget Act, the deadline for enacting these spending bills is always October 1. That means that, by law, Congress must pass twelve spending bills by October 1st to fund the government.

But Congress rarely meets the deadline. Because of this, congressional leaders have fallen back on two special types of spending bills—omnibus bills and continuing resolutions (CRs). Omnibus bills combine all twelve spending bills into one big package so that they’re all voted on at once. It’s a process that is supposed to be faster and more straightforward.

But even after eliminating most of the appropriations work, Congress has rarely approved the federal budget before the October 1 deadline. CRs are spending bills that also condense all federal spending into a single vote. They temporarily renew the last fiscal year’s funding. The appropriations committees use CRs to buy time to put together an omnibus bill.

Although speed and efficiency may be the excuse for these bundled spending bills, in effect they allow for, in the words of Clay Jenkinson, “a good deal of legislative mischief that would not stand up under a more deliberative process.”

Appropriations committee members can work with party leaders and lobbyists to shovel their ever-growing legislative agendas into these massive bills, throw in handouts to their friends and donors, and send the thousand-page bills off to Congress just hours before the vote.

And the all-or-nothing format of these bills leaves legislators no flexibility. To get the programs they want, they must green-light everything they don’t want. This setup makes the endless growth of government spending all but inevitable.

And that’s why a return to separate appropriations bills was a central demand of the House Republicans holding up McCarthy’s Speaker vote earlier this year. It is also why McCarthy’s plan to pass a CR before Sunday’s deadline faced resistance.

On a podcast last month, Gaetz said: “We made a commitment in January as part of the Speaker contest that we would not govern by having one up-or-down vote on every disparate agency of government through continuing resolutions or omnibus bills.”

McCarthy tried to appease his party’s right flank by bringing some members of the House Freedom Caucus on board to help craft a CR that included increased funding for border security and other initiatives sought by conservatives. But Gaetz and his allies refused to budge.

That left McCarthy with a choice: keep his word and endure some of the bad optics that come with a government shutdown or go around the conservative holdouts and work out a CR with the Democrats. He chose the latter, leading to the vote that cost him the gavel on Tuesday.

Perhaps the most striking part of this whole ordeal is how modest Gaetz’s demands are. Much of the media coverage these last few weeks would have you think he’s requiring massive spending cuts or deliberately trying to crash the economy out of some maniacal hatred for McCarthy. Instead, he’s just asking for his party’s leadership to abide by a previously agreed-upon procedural change, a procedural change that barely scratches the surface of what the federal government’s dire fiscal situation requires. As Ron Paul outlined in his column on Monday:

Federal spending is so out of control that it only took three months for the federal debt to increase by one trillion dollars to over 33 trillion dollars. In contrast, it took almost 200 years for the federal debt to reach one trillion dollars. So, the federal government racked up more debt in the last three months than it did from the ratification of the US Constitution until Ronald Reagan’s first term!

The scale of the national debt is a ticking time bomb. Ending omnibus bills and continuing resolutions is a solid first step toward dealing with this situation, but substantial spending cuts need to follow.

Above all, the government’s power to create money must be abolished. In his book Capitalism, George Reisman says, “All talk about balancing the federal budget is just so many empty words” as long as government spending is not constrained by tax revenue. “Even proposals for constitutionally balanced budgets cannot be taken seriously.” A return to a monetary unit beyond political control is required if this era of government by deficit is to end.

That’s the level of change necessary, but it won’t be easy or pleasant for politicians. They’ll have to stop kicking the can down the road and face the fact that our current economic trajectory is unsustainable. That will require the courage and maturity to face pain today to avoid a lot more pain in the future. If they fail to do so for a simple procedural change, they’re clearly not up for the job.

This article was originally featured at the Ludwig von Mises Institute and is republished with permission.