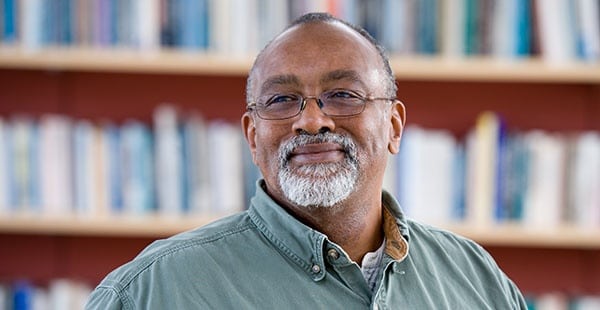

Glenn Loury, the economist at Brown University, often has interesting things to say. His YouTube Glenn Show episodes with linguist and social commentator John McWhorter feature valuable insights and eye-opening data about race, woke “anti-racism,” and related matters.

Loury is a neoclassical economist who is generally pro-market. He harbors some doubt about government solutions to social problems. But judging by what he says about immigration, his political theory is appallingly collectivist. This is alarmingly clear from his most recent video with McWhorter. (The transcript is here.)

Loury wants to separate the case for tight border control from the polarizing right-wing TV personalities like Tucker Carlson who constantly bang on about it. Loury’s purpose is to show that a perfectly nonracist case can be made for the government controlling “the border.” (The U.S, has more than one border, but Loury uses the singular form.) He says, in the typical alarmist right-wing manner:

Is it good for the country that we don’t have control of the border and that people come in the thousands and tens of thousands and ultimately in the millions without authorization?

So here’s an argument that I don’t think is a “swarthy hoard” argument. I am an American citizen. That’s a very special endowment which I have inherited in virtue of my birth. This is my country. There are 330 million or so of us. We should get to decide what the future of the composition of our polity is going to be through legitimate democratic deliberation. That’s what we elect representatives for. That’s the purpose of law.

He goes on to say that the American people should decide democratically, that is, collectively, who will and won’t “add[] positive value to the collective enterprise of the country.” It sounds more like he’s talking about a member-owned country club than about a (theoretically) free country.

I see three problems here. First, political decision-making in a representative democracy doesn’t work in the pollyannish way that Loury seems to imagine. Second, voters, politicians, and bureaucrats couldn’t acquire the information needed to ascertain who will and won’t “add[] positive value to the collective enterprise of the country.” And third, Loury’s approach runs roughshod over individual liberty, private property, and the pursuit of happiness. Aren’t those values our actual very special endowment inherited in virtue of our birth?

James Buchanan said that he helped found the Public Choice school of economics to achieve a “politics without romance.” By that he meant that if we are to understand the political realm, we must drop the civic-books fairy tales about well-informed voters and public-spirited politicians and bureaucrats. Instead, we must take people involved in politics as they really are. Politicians and bureaucrats do not become saints when they leave the private sector for government jobs. Even when they are not simply corrupt, they still have career ambitions and other self-interested motivations, like those outside the government.

A related point comes from the Austrian school of economics, specifically Ludwig von Mises and F. A Hayek, who showed beginning a century ago that central planners can’t possibly know all that they would have to know to guide a society’s commercial activities. It’s called “the knowledge problem,” and it’s why socialism and communism fail. The point also applies to governments that presume to plan immigration according to who will be productive and who will be parasitical. That “data” simply is not on deposit anywhere for the bureaucrats’ taking. Remember that we’re talking about human beings and a future that has yet to unfold.

Moreover, voter decision-making is distorted by perverse incentives inherent in the democratic system. As Bryan Caplan shows in The Myth of the Rational Voter: Why Democracies Choose Bad Policies, voters tend to indulge their unexamined irrational biases rather than spend their free time studying which positions and candidates would be best for their communities. But why would they indulge their irrational biases? They do so because it is costless to each of them: since no single vote is likely to be decisive, why would busy people trade time with family and friends for pointless research that will have zero impact on an election? One of those irrational biases is the bias against foreigners. (Caplan explains his data-rich thesis here. See my review of Caplan’s book.)

The point of all this is to show that Loury’s idealized democratic vision — in which well-informed voters with a birdseye view of the social landscape elect wise and altruistic representatives guided only by the general welfare who will deliberate on an immigration policy aimed solely at creating the scientifically determined optimal population for America, a policy that will then be administered by humane bureaucrats in the executive branch under the guiding hand of an enlightened president — is a chimera. Rather, the political arena is a sausage factory full of largely unaccountable career-, prestige-, and power-seekers; special interests; and voters, each of whom pays only a tiny bit of the full price of their foolish choices.

Lastly, Loury overlooks the neglected cost of a collectivist approach to immigration. What cost? The cost to individual Americans who would sell or rent to, buy from, hire, work for, and socialize with immigrants. (The terrible cost to those locked out is obvious). Don’t those Americans have rights? Why should their freedom to engage in voluntary relationships with non-Americans require government permission, even if that system is given a democratic gloss? As Chandran Kukathas emphasizes in his book Immigration and Freedom, restrictions on actual and would-be immigrants necessarily are restrictions on American citizens too. It is impossible to enact the former without enacting the latter.

Watch Loury in action:

If we don’t have control, and we simply allow anyone who has the resources to get themselves to the Mexican side of that border and wade across that river into the country, we will look up in 20 years, in 50 years and find that we are a different country than we had been in ways over which we did not exert the legitimate discretion that is our inheritance as citizens of the country. [Emphasis added.]

That’s a social engineer speaking.

Loury thinks he’s accomplished his goal: since blacks, he alleges, suffer disproportionately from “uncontrolled immigration” (as if we have that) “through the labor market or through competition for public resources,” border control could hardly be racially motivated. Does he not see the problem here? Border control might still be motivated by animus toward Mexicans, Latinos generally, or brown people, rather than black people, although I accuse Loury of none of that.

As for his concern about the labor market and public resources, that is, tax revenue, Loury should know better. Immigration experts associated with the Cato Institute and elsewhere have shown repeatedly over many years that immigrants hugely benefit Americans generally on net and in fact the whole world. Immigrants are producers as well as consumers, and their crime rates and consumption of tax-funded benefits are relatively low. If Loury is worried about new arrivals’ going on the dole or lowering the wages of the high-school dropouts, he could propose, as second-best solutions, relevant welfare restrictions on new arrivals (they exist for the most part already) or assistance to the small number of low-skilled workers adversely affected in the job market. He could also propose that the government abolish myriad obstacles to creating businesses and housing. Instead, he proposes to keep people he deems unproductive out of the country, people who desperately want to make better lives for themselves and their families in America. Shame on him.

Again citing Caplan, significant wealth creation is to be expected from even the poorest immigrants in America because their productivity vastly increases when they move from capital-poor to capital-rich environments. Machines magnify the power of human labor. Moreover, the more people in a productive environment, the more minds there are to contribute new ideas that will combine with other ideas to become even better ideas. The result is a rising living standard for all. As Julian Simon put it, human ingenuity is the “ultimate resource.”

Thus, as Caplan says, an open-border policy is the most effective antipoverty program imaginable. Keeping poor people locked in undeveloped countries is simply cruel. (See Caplan’s graphic novel, Open Borders.)

Loury doesn’t mention culture in his case against freedom of movement, but it’s hard to believe that he doesn’t also have that in mind. Suffice it to say here that asking politicians to conserve “the culture” seems, to say the least, ill-advised — even if it were possible.

I’ll close with one more quote from Loury:

So who I don’t want to come? Anybody who doesn’t have my permission to come. Beyond that, if you were to ask me, and there are more people who want to come than there are “places” for them to come, and we have to decide how many places we want to make available for people to come, I would say, people who are going to come and be a dependent on the rest of us for their support are less desirable than people who want to come and who are going to start businesses or bring skills or things of this kind.

Here we see Loury falling back on the discredited fixed-pie model of society. More people than places for them? Immigrants in a free market create their own places. We also see Loury the soothsayer, for he apparently knows who will be dependent and who will be productive, who will start businesses and who won’t. Wouldn’t it be nice if the rest of us could see the future so clearly?