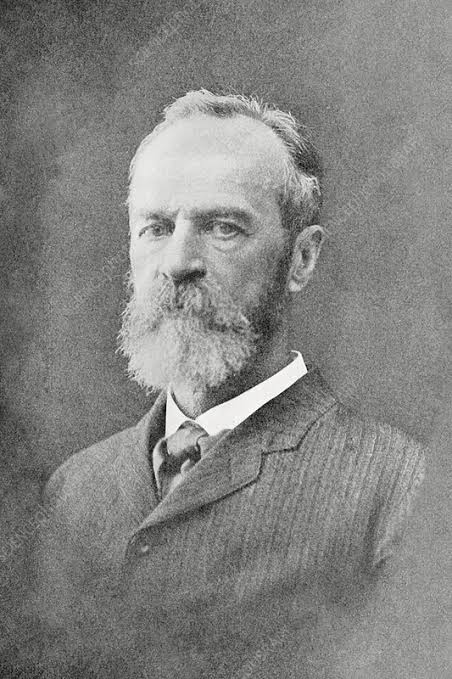

Readers may have wondered about a quote I used from Ludwig von Mises recently. In his book Liberalism Mises distinguished the (classical) liberal case against war from what he called the “humanitarian” case against war. To understand Mises, let’s examine a “humanitarian” on the war question: philosopher, psychologist, and eugenicist William James (1842-1910). Is it relevant to the largely illiberal antiwar movement today? Let’s see.

Whether Mises was thinking of James when the great economist wrote the “peace” section of Liberalism (1926), I cannot say. He may well have. James had given a lecture titled “The Moral Equivalent of War,” which appeared in his book Memories and Studies (1911). It’s an instructive lecture, and antiwar thinkers and activists should read it. James said:

The war against war is going to be no holiday excursion or camping party. The military feelings are too deeply grounded to abdicate their place among our ideals until better substitutes are offered than the glory and shame that come to nations as well as to individuals from the ups and downs of politics and the vicissitudes of trade. There is something highly paradoxical in the modern man’s relation to war.

James believed that while no American would wish for another “war for our Union” (that is, war of secession), neither would anyone vote to have it “expunged from history, and the record of a peaceful transition to the present time substituted for that of its marches and battles.” In other words, James said, modern Americans have a love-hate relationship with war. War’s blood, death, and destruction were not enough to put them off its inherent bravery, heroism, and discipline—virtues that men have celebrated for millennia. The war ethic is hardwired into us, James thought.

The question James raised was how could society have the glory without the gore.

Modern war is so expensive [James continued] that we feel trade to be a better avenue to plunder; but modern man inherits all the innate pugnacity and all the love of glory of his ancestors. Showing war’s irrationality and horror is of no effect upon him. The horrors make the fascination. War is the strong life; it is life in extremis; war-taxes are the only ones men never hesitate to pay, as the budgets of all nations show us. [Emphasis in the original.]

James thought he had a solution. “In my remarks, pacificist though I am,” he said, “I will refuse to speak of the bestial side of the war-regime (already done justice to by many writers) and consider only the higher aspects of militaristic sentiment.” (Emphasis added.)

Higher aspects indeed. Today’s neoconservatives and other militarists would agree.

Reflective apologists for war at the present day all take it religiously. It is a sort of sacrament. Its profits are to the vanquished as well as to the victor; and quite apart from any question of profit, it is an absolute good, we are told, for it is human nature at its highest dynamic. Its “horrors” are a cheap price to pay for rescue from the only alternative supposed, of a world of clerks and teachers, of co-education and zo-ophily, of ” consumer’s leagues” and ” associated charities,” of industrialism unlimited, and femininism unabashed. No scorn, no hardness, no valor any more! Fie upon such a cattleyard of a planet! [Emphasis added.]

So far as the central essence of this feeling goes, no healthy minded person, it seems to me, can help to some degree partaking of it. Militarism is the great preserver of our ideals of hardihood, and human life with no use for hardihood would be contemptible. Without risks or prizes for the darer, history would be insipid indeed…. [Emphasis added.]

Note that James was describing a worldview, which he seemed to share, that denigrates the supposedly boring bourgeois life without hardihood, the private individualist life of free association, family, friends, community, productive work, and increasing consumption. How insipid! Who could stand that? If that’s the alternative to war, give us war!

Pacificists, said James, made a big mistake by failing to appreciate what would be lost if peace reigned: the “supreme theatre of human strenuousness…, and the splendid military aptitudes of men.”

The military party denies neither the bestiality nor the horror, nor the expense [of war]; it only says that these things tell but half the story. It only says that war is worth them; that, taking human nature as a whole, its wars are its best protection against its weaker and more cowardly self, and that mankind cannot afford to adopt a peace-economy. [Emphasis in the original.]

Get that? War protects us from our cowardly selves! Peace is prohibitively expensive! So, Professor James, do tell us how the case against war should be made so as not to alienate those who know its true value.

I do not believe that peace either ought to be or will be permanent on this globe, unless the states pacifically organized preserve some of the old elements of army-discipline. [Emphasis added.]

Hang on. Look at what he said: peace ought not to be established if the “old elements of army discipline” are eliminated. He went on:

A permanently successful peace-economy cannot be a simple pleasure-economy. In the more or less socialistic future towards which mankind seems drifting we must still subject ourselves collectively to those severities which answer to our real position upon this only partly hospitable globe. [Emphasis added.]

When he said we must “subject ourselves collectively” to severities, he really meant that some people, the rulers, should subject other people, the ruled. May we who are ruled decline?

We must make new energies and hardihoods continue the manliness to which the military mind so faithfully clings. Martial virtues must be the enduring cement; intrepidity, contempt of softness, surrender of private interest, obedience to command, must still remain the rock upon which states are built—unless, indeed, we wish for dangerous reactions against commonwealths fit only for contempt, and liable to invite attack whenever a centre of crystallization for military-minded enterprise gets formed anywhere in their neighborhood. [Emphasis added.]

Obedience and the surrender of private interest must be preserved even when war is abolished? Apparently so.

The war-party is assuredly right in affirming and reaffirming that the martial virtues, although originally gained by the race through war, are absolute and permanent human goods. Patriotic pride and ambition in their military form are, after all, only specifications of a more general competitive passion. [Emphasis added.]

Yet a better form of patriotism may come along, he said, and already has done so for some people. He called it “civic passion.”

It is only a question of blowing on the spark till the whole population gets incandescent, and on the ruins of the old morals of military honor, a stable system of morals of civic honor builds itself up. What the whole community comes to believe in grasps the individual as in a vise. The war-function has grasped us so far; but constructive interests may some day seem no less imperative, and impose on the individual a hardly lighter burden. [Emphasis added.]

So choose your vise: war collectivism or peace collectivism. Individualism, freedom, and unrestricted consensual market relations are not on the menu.

Thus socialism fulfilled James’s humanitarian requirements. It is war by other, bloodless means. It would provide military discipline and social unity without the mangled bodies. So, for example, “accidents of birth and opportunity” (that is, inequality) could be addressed by “a conscription of the whole youthful population to form for a certain number of years a part of the army enlisted against Nature, the injustice would tend to be evened out, and numerous other goods to the commonwealth would follow.” (Emphasis in the original.)

Yes, a civilian draft for our own good, of course.

Such a conscription, with the state of public opinion that would have required it, and the many moral fruits it would bear, would preserve in the midst of a pacific civilization the manly virtues which the military party is so afraid of seeing disappear in peace. We should get toughness without callousness, authority with as little criminal cruelty [!] as possible, and painful work done cheerily because the duty is temporary, and threatens not, as now, to degrade the whole remainder of one’s life….

The martial type of character can be bred without war….

We should be owned, as soldiers are by the army, and our pride would rise accordingly. [Emphasis in the original.]

I sense that today’s progressives and national conservatives would applaud our being owned by the great collective. An aside: James didn’t say how dissenting individualists would be treated. A bloodless firing squad perhaps?

Now we can see what Mises meant when he wrote:

There are high-minded men who detest war because it brings death and suffering. However much one may admire their humanitarianism, their argument against war, in being based on philanthropic grounds, seems to lose much or all of its force when we consider the statements of the supporters and proponents of war. The latter by no means deny that war brings with it pain and sorrow. Nevertheless, they believe it is through war and war alone that mankind is able to make progress. War is the father of all things, said a Greek philosopher, and thousands have repeated it after him. Man degenerates in time of peace. Only war awakens in him slumbering talents and powers and imbues him with sublime ideals. If war were to be abolished, mankind would decay into indolence and stagnation.

It is difficult or even impossible to refute this line of reasoning on the part of the advocates of war if the only objection to war that one can think of is that it demands sacrifices. For the proponents of war are of the opinion that these sacrifices are not made in vain and that they are well worth making. If it were really true that war is the father of all things, then the human sacrifices it requires would be necessary to further the general welfare and the progress of humanity. One might lament the sacrifices, one might even strive to reduce their number, but one would not be warranted in wanting to abolish war and to bring about eternal peace.

So what’s the alternative case?

The liberal critique of the argument in favor of war is fundamentally different from that of the humanitarians. It starts from the premise that not war, but peace, is the father of all things. What alone enables mankind to advance and distinguishes man from the animals is social cooperation. It is labor alone that is productive: it creates wealth and therewith lays the outward foundations for the inward flowering of man. War only destroys; it cannot create. War, carnage, destruction, and devastation we have in common with the predatory beasts of the jungle; constructive labor is our distinctively human characteristic. The liberal abhors war, not, like the humanitarian, in spite of the fact that it has beneficial consequences, but because it has only harmful ones. [Emphasis added.]

The peace-loving humanitarian approaches the mighty potentate and addresses him thus: “Do not make war, even though you have the prospect of furthering your own welfare by a victory. Be noble and magnanimous and renounce the tempting victory even if it means a sacrifice for you and the loss of an advantage.” The liberal thinks otherwise. He is convinced that victorious war is an evil even for the victor, that peace is always better than war. He demands no sacrifice from the stronger, but only that he should come to realize where his true interests lie and should learn to understand that peace is for him, the stronger, just as advantageous as it is for the weaker.

Give me a (full) liberal over a humanitarian every time.