“Nothing so diminishes democracy as secrecy,” as Attorney General Ramsey Clark warned in 1967. As a journalist, I have battled federal agencies for decades to try to discover the sordid details of how Americans’ rights and liberties are being shafted. Most government cover-ups succeed because the game is rigged in Washington to blindfold citizens to most federal abuses and boondoggles. But sometimes I found ways to penetrate bureaucratic iron curtains.

A few decades ago, trade policy was one of the hottest issues in Washington. Pat Buchanan was revving up his presidential campaign and protectionism—closing American ports to the goods that the world produced—was one of his top goals. President George H. W. Bush was demagoguing against Japanese imports and his appointees were multiplying trade restrictions that were shafting American manufacturers and skewering American consumers.

Both Buchanan and Bush relied on a political storyline that was pure hokum. America was supposedly being victimized by its free trade policies, while the other governments in the world were conniving to unfairly victimize American industry.

I wrote often about trade policy, exposing the machinations of the Commerce Department, Customs Service, the U.S. Trade Representative, and the U.S. International Trade Commission. I could not understand how the myth that the U.S. was a free trade nation survived a cursory examination of the U.S. tariff code. At that point, the feds were imposing 8,753 different taxes on imports. While the average American tariff was around five percent, some tariffs were in the stratosphere.

The tariff code looked like class warfare at its worst. Mink furs were duty free—but polyester sweaters for babies carried a 34 percent tariff. Lobster was duty free—but infant food preparations carried a 17 percent tariff. Orange juice carried a 40 percent tariff, but fancy French water paid less than 1 percent. Tariffs on cheap shoes were 67 percent. Worst of all, cheap cigars were hit by a tariff three times higher than that levied on premium cigars—stark evidence of the tariff code’s anti-redneck bias.

But the actual tariff level for thousands of categories of imports was practically invisible, and my hunch was that those were the most prohibitive trade barriers imposed by the U.S. government. Many tariffs were based not on import prices, but on the weight or count or other measure of the imported product. This made it almost impossible to explain how much taxes Americans were being forced to pay.

I contacted several federal agencies seeking to find out exactly what the percentage tariffs were for those thousands of cryptic categories. I was told again and again that no such information existed.

I took a break from that, instead finishing the book on trade policy for a foreign trip in 1990. I was roaming Europe with a Eurail pass and stopped in Geneva, Switzerland to visit the General Agreement for Trade and Tariffs (subsequently renamed the World Trade Organization). GATT headquarters looked like a mix between a fortress and a castle for international bureaucrats. When I entered, the guards searched everything except my socks and they double-pawed the bicycle courier bag I use as a briefcase. I felt like a lawyer going to visit a client on death row.

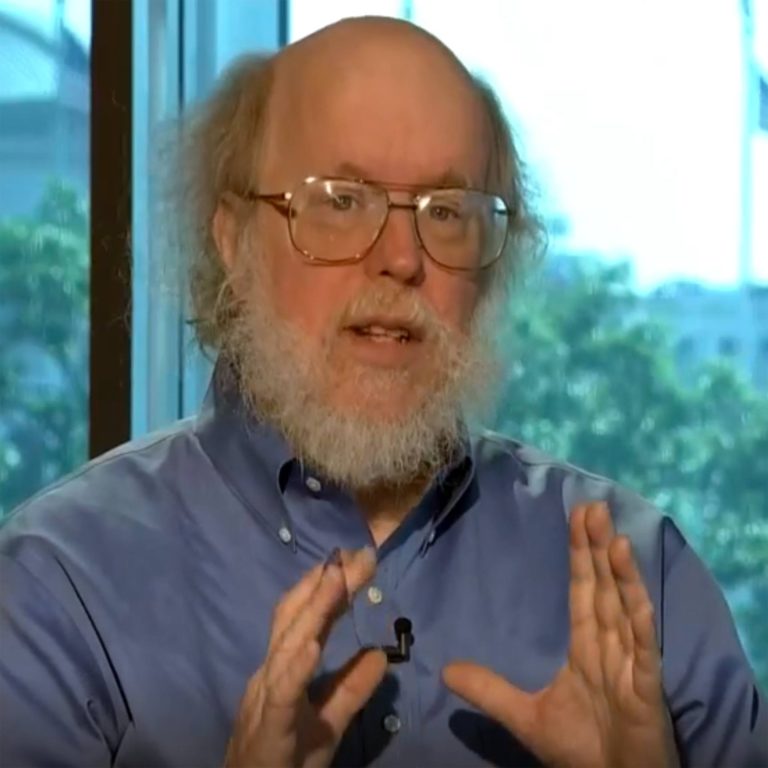

I had an appointment with the honchos who administered the international textile import quotas regime, a byzantine creation designed to throttle Third World clothing makers. The textile office was at the far end of a building that seemed as long as a football field. After palavering with those guys, I was walking back down that endless hallway, and I saw a rickety card table stacked high with thick documents. As I got closer, I noticed that the door next to the table was labeled Tariff Negotiations, and those documents were titled “U.S. Proposal for Market Access Negotiations,” decorated with the word SECRET in huge print.

I slowed down and my entire life flashed before my eyes—all those years attending Presbyterian Sunday School and being in the Boy Scouts. But I couldn’t get past a line from one of my favorite Doonesbury cartoons: “But the pension fund was just sitting there!”

There were at least 20 copies on that table. These were extras, right? Maybe headed to a recycling bin?

Actually, I never even came to a full stop. Perhaps propelled by sheer guilt over the secrets it was unjustifiably keeping, one of those 500-page documents damn near leaped into my courier bag as I wandered down that hall.

But I wondered, would the guards search me on the way out? The information in that document might have been covered by U.S. laws prohibiting possession of confidential data in international negotiations. As I came up to the guard desk, I said something in garbled German or even worse French and the guards shrugged and waved me on. They were used to hearing Americans butcher all the languages spoken in Switzerland.

Heading back to my hotel, I flipped through the document quickly, and recognized that I had a Rosetta stone for U.S. protectionism. But I was concerned that someone might have noticed me taking a loaner copy from that table. And the GATT folks knew where I was staying, since I had phoned from the hotel to arrange the interview.

Arriving back in my hotel room, I announced to my then-wife (who was German) as she puffed on a Marlboro: “We are leaving the country—right now. I’ll explain at the train station.” “Was ist los? Ach du lieber Himmel!” (think: goodness gracious) was the gist of her response. No wonder she was always kind of jumpy when we traveled together after that.

We hopped the next train out of the country.

Once I was back in Washington, I called the chief tariff official at the U.S. Trade Representative’s Office. I had never met this woman in person; I only knew her as a telephone voice who always sounded peeved when I called.

“I need to confirm some data on U.S. tariffs,” I said in a blasé tone.

“Huh,” she replied.

“For tariff code line 9108.91.20 – that’s low-priced watches – the tariff is 151%, right?”

I paused but heard nothing.

“For tariff code line 2401.30.60 – that’s tobacco stems – the tariff is 458%, right?”

Another fruitless pause followed.

“For tariff code line…”

“WHERE DID YOU GET THOSE NUMBERS?!!” she exploded.

“From the U.S. Government’s March 15 GATT proposal.”

“THAT’S CONFIDENTIAL INFORMATION!”

“I reckon. The word SECRET is stamped on every one of the 500 pages. But I’ve still got to verify it.”

Lamentably, she slammed down the phone before I could tell her to have a nice day.

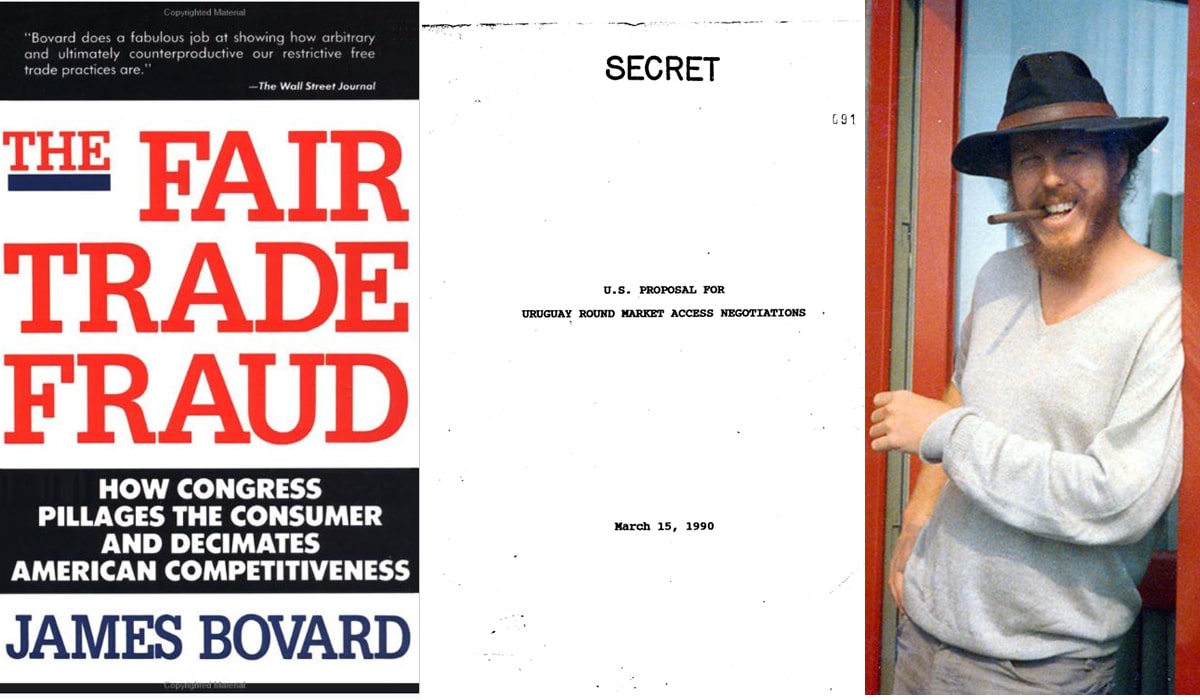

Those sky-high tariffs had a starring role in my 1991 book, The Fair Trade Fraud (St. Martin’s Press) and helped obliterate the U.S. government’s free trade vestal virgin promenade.

Some folks might criticize me for conveying that tariff report. But it was a U.S. government document, my tax dollars paid for it, and Americans had a right to know what it said. It wasn’t like it had national security secrets such as the details of C.I.A. torture or illegal National Security Agency wiretapping. And I had asked several federal agencies for that information and was told it didn’t exist. But there is a basic rule in D.C.:

If government officials lie to you, it is public service.

If you lie to them, it’s a felony.

My writings on trade were condemned by U.S. International Trade Commissioners, top Commerce Department officials, and a vanload of congressmen who probably failed Econ 101. Actually, failing economics seems to be a job requirement for U.S. trade policymakers.

I was mystified why pundits and politicians who railed against imports never took the time to examine the dirty details of trade policy. For most congressmen, setting tariffs was an exercise in know-nothing industrial policy. Most congressmen who reigned over the tariff code’s hundreds of different chemical taxes probably could not play with a junior chemistry set without blowing themselves up.

Tariffs were living proof of a political system’s inability to correct its economic mistakes. A 1984 Federal Trade Commission study estimated that tariffs cost the American economy $81 for every $1 of adjustment costs saved. The tariff code inherited and perpetuated handouts for the biggest political contributors to previous generations of congressmen. The sheer lethargy of the American political system allowed high tariffs to continue long after the original payoff recipients turned to dust in the Congressional Cemetery in southeast Washington.

Unfortunately, as long as politicians can profiteer from restricting imports, protectionism will continue reviving. President Donald Trump subverted the competitiveness of American manufacturers with his steel and aluminum tariffs, even though those levies helped destroy an estimated 300,000 jobs. And President Biden is perpetuating Trump’s tariffs despite the disruptions they are inflicting. Most of the media continues to ignore the economic carnage resulting from protectionist decrees that, after all these years, still cannot pass the laugh test.

This article was originally featured at the American Institute for Economic Research and is republished with permission.