Taiwan is today lauded for its vibrant democracy, open economy, and progressive society. However, behind this shining exterior is a dark and brutal history that is frequently overlooked; or in the case of Washington and its loyal corporate mouthpieces, purposefully ignored.

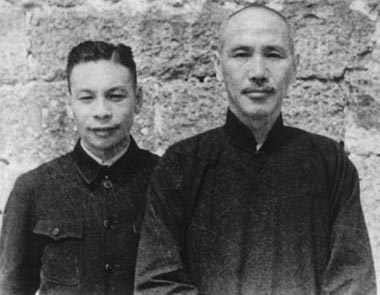

For before its democratization in the 1990s, Taiwan was a harsh authoritarian police state under the rule of Chiang Kai-shek and his son Chiang Ching-kuo. This period, marked by severe repression and systemic terror, is an essential chapter in Taiwan’s history that Americans should know, particularly given the enduring resentment Washington’s vital support for the regime engendered and the purported reasons for the necessity of the island’s defense.

The roots of Taiwan’s authoritarianism can be traced back to the retreat of Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist government (Kuomintang, or KMT) to Taiwan after losing the Chinese Civil War to the Communists in 1949. The local population had already received more than an inkling of what awaited, the KMT authorities having already in 1947 brutally suppressed a popular protest against KMT corruption, mistreatment, and misrule on the island. Facing a precarious situation and the ever-looming threat of a Communist invasion, once arrived on the island Chiang established a regime that relied heavily on surveillance, repression, and brutality to maintain control.

Central to this regime was the role of Chiang Ching-kuo, Chiang Kai-shek’s son, who was instrumental in the creation and operation of Taiwan’s police state. Having spent formative years in Stalin’s Moscow, Chiang Ching-kuo learned from the Soviet Union’s tactics of surveillance, infiltration, and terror. Upon his return, he applied these methods to serve his father’s regime, becoming a formidable spy chief whose skills ensured the perpetuation of KMT rule in Taiwan.

Chiang Ching-kuo’s police force penetrated almost every facet of life in Taiwan. Officially, their task was to arrest enemies of the state, countering Communist subversion; in practice, this mission translated into the suppression of virtually any source of potential dissent, contributing to what became known as the White Terror.

This White Terror, the period of martial law in Taiwan, lasted from 1949 until 1987, and was marked by widespread human rights abuses, including arbitrary arrests, torture, and executions. The true scale of the repression remains difficult to ascertain, as the regime was as thorough in erasing records as it was in executing its campaigns of cruelty. But estimates suggest that tens of thousands of Taiwanese were imprisoned, with thousands more executed during this period.

One of the most notorious sites associated with the White Terror was Green Island, a remote volcanic isle in the Pacific Ocean. This desolate prison camp housed many of Taiwan’s political prisoners, some of whom were imprisoned for decades. The mere suspicion of dissent could lead to incarceration—constitutional guarantees of due process being but the thinnest of veneers.

From its inception, then, “Free China”—as Taiwan was referred to by the KMT—was a misnomer, purposefully cultivated by Taipei and propagated by the China lobby and its beneficiaries in Washington, people like Time and Life magazine founder and owner Henry Luce or Congressmen Walter Judd and Senator William Knowland. In truth, the regime’s foundation was built on authoritarianism and terror, justified as necessary evils to ensure his regime’s stability.

It was, in the words of historian Sulmaan Wasif Khan, a choice between “two tyrannies.”

The foolish insistence of FDR that Taiwan be granted to Chiang’s crumbling ROC regime, then Harry Truman and Dwight Eisenhower’s determination to keep that regime in power, played an obviously critical role in creating the circumstances that prevail to the present day: a Chinese Civil War never concluded.

Of course, despite the harsh repression of Chiang and his ilk the seeds of resistance slowly began to sprout. By the 1970s and 1980s, the pressure for political reform grew, spurred by both internal and external factors. Taiwan’s economic success and the global trend towards democratization played crucial roles—as did the death of Chiang Ching-kuo and the subsequent rise of Lee Teng-hui, who led Taiwan towards democratization.

Understanding Taiwan’s past is crucial for appreciating its present—particularly for Americans, who are told that the necessity of defending Taiwan stems, to varying degrees, from its status as a democracy, it should be clear that wasn’t and isn’t the reason for Washington’s policy.

It was and remains a function of Washington’s determination to be the dominant global power everywhere, forever. The inevitable march of history be damned.