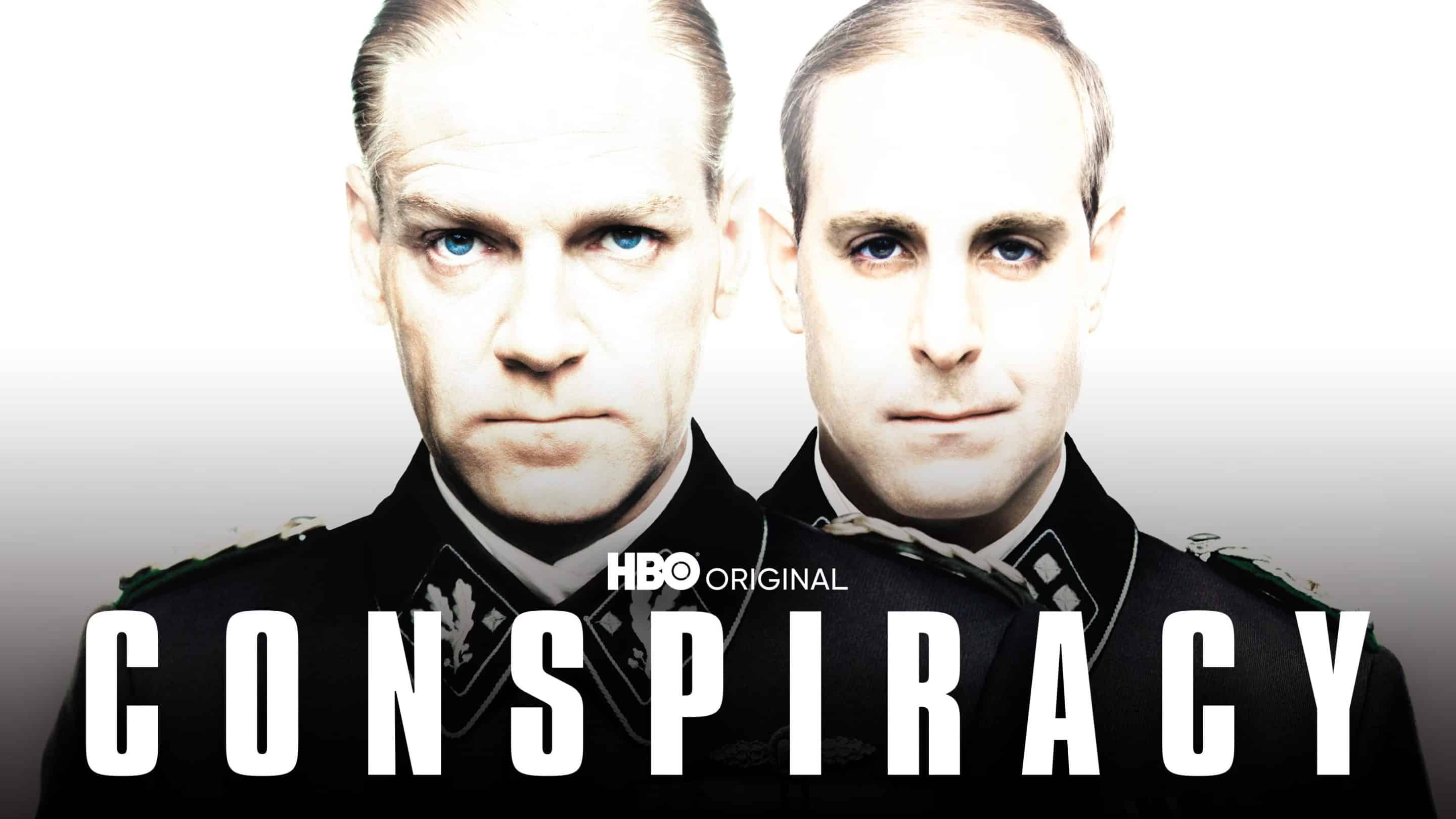

The 2001 film Conspiracy is an HBO production about the sinister 1942 Wannsee conference attended by fifteen upper echelon Nazi German bureaucrats, military and department heads. It was the first of two meetings with the intention of solving the “Jewish problem.” With the backdrop of war, emigration and mass incarceration had either failed or become resource draining. It was then decided by the German government to eliminate all of the Jews of Europe. In the initial two hour meeting led by SS man Reinhard Heydrich, it was concluded that death camps would be built and gas used to execute around sixty thousand Jews a day, solving the Reich’s problem.

The film is a dramatic depiction of events, based on very limited information but with painstaking research. The historical nature of the film is significant, an example of the legal and expedient measures required by government to do what would otherwise be considered impossible. It’s also an insight into the characters of history who participated in a great terror against humanity. Those in attendance varied from the vile antisemitic who wanted the mass death of every Jewish person, to those who naively assumed that the undesirables would be contained or legally restricted while receiving humane treatment. Then there were those in between who saw the labor potential of slaves rather than the ideological need to eradicate all Jews from the species as a solution.

If the film was the have a moral voice it would be Wilhelm Kritzinger (David Threfall), who represented the Reich Chancellery. He expresses initial ignorance as to what was occurring to the Jewish population, a miscommunication between his department and the reality. Bullied and threatened ever so subtly by the ice cold Heydrich, played chillingly by Kenneth Branagh, we see the nature of politics and its poison as egos and agendas transcend any debate or reason. Instead, self interest and ideology prevail. After the conference Kritzinger attempted to resign, but was denied.

The die hard national socialists are less interesting than those shown with character and nuance. The efficient stone hearted Nazi is easy to imagine; Stanley Tucci’s portrayal of Eichmann is perfect as the pariah. Though common and crucial to the regime, such men do not convey the relatable human being. Whereas Dr. Wlhelm Stuckart, played by Colin Firth, is very human, as one of the co-authors of the Nuremberg code, a set of laws devised to determine what a Jewish person was and how they should be handled by the state according to their amount of “Jewishness.” He understands the importance of law rather than adhoc decision making. A proud and devoted Nazi, he is also aware of the importance of the rule of law for a stable government. For Heydrich and the SS, he is an important person to be convinced, and with persuasion he yields.

Most interesting is Dr. Rudolf Lange (Barnaby Kay), who is the commander of death squads in Latvia. Early on he asks for clarification as the word “evacuate” is being used ambiguously. Fresh from eliminating around thirty thousand Jewish civilians, he seeks clarification.

“I have the real feeling I ‘evacuated’ 30,000 Jews already, by shooting them, at Riga. Is what I did, ‘evacuation?’ When they fell, were they ‘evacuated?’ There are another 20,000, at least, waiting for similar ‘evacuation.’—I just think it is helpful to know what words mean…with all respect.”

They were in fact “evacuated.” The clarification is a cold shot to those either naive to the real nature of their government and ideology and those who conceal their morality beneath such euphemisms. Lange as portrayed by Kay expresses a discomfort with the shootings and nature of mass killings, though he clarifies that he is a soldier that respects the chain of command. That’s a moral removal of responsibility. He also states, that as a trained lawyer, he is “distrustful of language.” Most of those in attendance were trained lawyers.

Others in attendance showed reservations to varied degrees from Erich Neumann (Jonathan Coy), director of the office of the Four Year Plan, who considered mass executions as a waste of labor potential. Instead he pushed for sterilization, rather than elimination. The Holocaust was already underway during the conference, though it was not as systemic and had not become the sole solution as such. SteriliZation had also been used against hundreds of thousands of individuals under racial hygiene laws. The discourse among those in attendance was between practical realities and utility of their victims in the war effort conceeding to the ideological fulfilment of hatred culminating into genocide. Interestingly enough, Otto Hoffman (Nicholas Woodeson) as SS chief of Race and Settlement Main Office displays unease and a sickness over the revelations of what is being tabled despite his uniform and Nazi credentials.

Despite any reservations, whether moral or pragmatic, in regards to the Holocaust the men in attendance validated the mass murder with a legal and bureaucratic framework so that thousands of willing killers would be more capable at murdering innocent civilians. The fascinating thing about all government is that the killer, those who push their victims into a gas chamber or pull the trigger themselves, can at times feel removed of any responsibility for what they are doing. It is a lawful act; they are following orders and respecting the authority that is sacred to them. Those in positions of power use legalese to elevate vulgar violence into a higher form of policy. Contemporary euphemisms to “cleanse Gaza” for example or to “bring peace to the Middle East” can disguise a true meaning of real intention.

The disconnect from the spilt blood and screams is not unique to the Nazi Germany, but is ever present today. We can see it in the distinction between what a genocide is and is not, argued in bland academic language or defined with loyalties based in bigotry or national self interest. Friendly powers do not commit genocide, only the pariah ones do. So, euphemisms are required to lessen the graphic nature of starvation, sniping, and bombing cities—or even walking into a hospital dressed as civilians to assassinate a man in a coma.

All are decisions made by seemingly intelligent, often educated and rational minded people to be acted upon by individuals who tend to view themselves as instruments without morality or intellect, who obey orders and kill with enthusiasm or cold professionalism. It is how Laos and Cambodia can become saturated by bombs and chemicals, Gaza a place of carnage or Afghanistan a hinge point of empires to wage war. It is all chaos conjured up by planners who boasted stability and order. It is arrogance and irresponsibility born from the pretence of rule.

Those in attendance at Wannsee were not good people. They very much human, just not good. That is the frightful thing about history, the most evil and destructive are very much human beings. They are more than just killing machines. Often such people are capable of laughter and can be charming, even have the potential for sentimentality. Then you also have the cold blooded killers who execute regardless, the useful tools of the state, the Eichmann’s or Lange’s. No genocide is possible without such people.

The magic of government is to reward careerism, cynicism, and ideological zealotry. The ideology of hatred common in fascist and communist forms of government is on full display in the film. After the conference, Kritzinger tells Heydrich a story that portrays such. Heydrich later retells the story to a handful of his comrades:

“This man hated his father. Loved his mother fiercely. The mother was devoted to him but the father used to beat him, demeaned him, disinherited him. Anyway, this boy grew to manhood and was still in his thirties when the mother died, this mother who had nurtured and protected him. She died. The man stood as they lowered her casket and tried to cry but no tears came. The man’s father lived to a very extended old age, withered away and died when the son was in his fifties, I think, and at the father’s funeral, much to his son’s surprise, he could not control his tears. He was wailing, sobbing. He was apparently inconsolable. Lost, even.”

Heydrich further explains to Eichmann, “The man had been driven his whole life by hatred of his father. When the mother died, that was a loss. When the father died, the hate had lost his object, then the man’s life was empty. Over.”

Ideology will always find hate, both at home and abroad. It allows for scapegoats, justifies power, and ensures the elimination of liberty. The collectivist war on abstracts and human beings knows no bounds and is so deeply embedded in their ideology. It’s not unique to Nazi Germany, although it’s frowned upon to compare any other government, but these traits tend to be universal. Among the fifteen in attendance no wisdom prevailed, only the emergence of an ideological certainty. A certainty that was ultimately self-defeating.

In a discussion with Gilbert Achcar, Noam Chomsky retells an interaction he had in in 1970 with Arthur Schleisinger Jr. while both were testifying before a U.S. Senate hearing on the Vietnam War. Chomsky had been critical of the John F. Kennedy administration, which Schleisinger had served in. Schleisinger turned to Chomsky and said, “You know, the problem with your analysis is that you’re underestimating the stupidity of planners.” Despite their academic pretensions, and the prestige of uniforms, titles, confidence, and wealth, all central planners, especially the more tyrannical a state becomes, suffer from a god delusion. In Conspiracy, considerations, concerns, and morality itself was brushed aside for an expedient conclusion that a few had already determined to be so.

As a film it stands in the category of 12 Angry Men, a small location that concentrates very distinct characters while they deliberate over the life of a stranger. In this case, the lives of millions of strangers. Personalities, pride, ego, and bigotry are ever present and while in the former a moral wisdom and conviction of reason prevails, that is not the case in Wannsee, 1942.The film concludes by showing the fates of each of those in attendance, some of which survive until the early 1980s, dying naturally and free.Others die before the war’s end, or soon after.

However empathetic the central planner may come across in depictions or even in person, the violence of government empowers them with an ability to not only steer other’s lives but to ruin them, often thousands at a time. Conspiracy is a film that allows us to witness an extreme case of how planners view human life, while they themselves live above the rest. We assume progress because the scale of such genocide has eluded us, yet we have witnessed the stab wounds and pin pricks of similiar mass murder. Even now the innocent bleed while the planners plan and the killers obey.