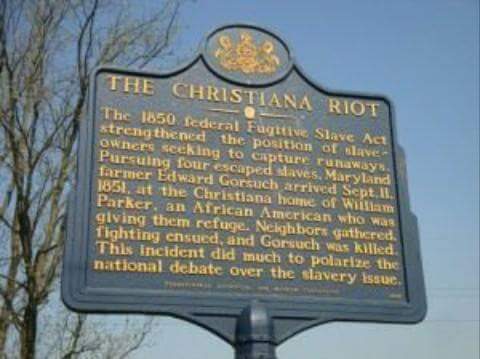

Given the rarity of the surname, it is likely that Supreme Court nominee Neil Gorsuch is related to deputy federal marshal Edward Gorsuch, who was killed in a violent episode that left the nation shocked and terrified, and was an overture to a long and bloody military conflict.

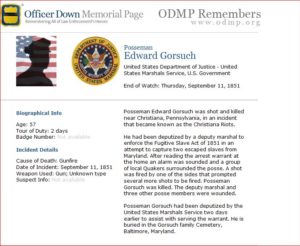

Deputy Marshal Gorsuch was 57 years old at the time he received his commission, and was killed on the second day of his service. The US Marshals Service deputized him on September 10, 1851, to enforce a warrant issued under the Fugitive Slave Law to recover two human beings Gorsuch claimed as his property. He and Marshal Henry H. Kline, along with several other deputies, had the “law” on their side when they traveled to Christiana, Pennsylvania, bearing a warrant that authorized them to abduct four men who had freed themselves – and to conscript any white citizen they encountered to serve as accomplices in that act.

Late in the evening of September 10, the kidnappers, who included at least two of Gorsuch’s sons, surrounded a two-story fieldstone home owned by William Parker, a 29-year-old farmer and militia organizer who had escaped from slavery nine years earlier. Operatives of the Underground Railroad had warned Parker of the impending raid.

Gorsuch imperiously demanded the surrender of his former captives. When no answer came from inside the home, the marshals invaded the domicile – and were promptly driven out by the occupants, one of whom wielded a pitchfork.

Standing in the front yard of the home, the marshals read the warrants to Parker, who looked down on them contemptuously from a second-floor window.

“I don’t care about your warrant, your demands, or your government,” Parker replied. “You can burn us, but you can’t take us. Before I give up, you will see my ashes scattered on the earth.”

“I want my property, and I shall have it,” bellowed Gorsuch, pretending as if words scribbled by a functionary on a piece of paper gave him a title of ownership over other human beings. Realizing that such a claim would avail nothing with Parker, Gorsuch appealed to biblical passages enjoining servants to obey their masters.

Parker, who apparently knew the Bible better than Gorsuch, replied by citing New Testament verses teaching the equality of all human beings before God.

“Where do you see it in Scripture that a man should traffic in his brother’s blood?” Parker demanded of the deputy marshal.

“Do you call a n*gger my brother?” Gorsuch exclaimed.

“Yes, I do,” Parker defiantly replied.

The situation congealed into a standoff that lasted until daybreak. Shortly after dawn, Parker’s wife used a horn to summon help from Parker’s militia, who arrived bearing whatever weapons they could muster. The alarm also brought two local Quakers named Elijah Lewis, a shopkeeper, and Castner Hanway, a local miller. Both of these white men were well-known for their sympathies toward escaped slaves.

Relieved by the arrival of two white men, Marshal Kline waved his warrant in their face and told them that they were required to assist in the recovery of Gorsuch’s “property.” Once again, this demand was in harmony with what the federal government called the “law” – and when Lewis and Hanway replied that they would have no part in an abduction they were told that they were committing a federal “crime.”

Surrounded, outnumbered, hungry, and humiliated, Deputy Marshal Gorsuch lost what remained of his composure.

“I have come a long way and I want my breakfast,” he snarled at Parker. “I’ll have my property, or I’ll breakfast in hell.”

“Go back to Maryland, old man,” one of the black militiamen taunted Gorsuch.

“Father, will you take all this from a n*gger?” asked his twenty-year-old son, Dickinson, who was part of the posse.

Parker snapped at Dickinson to keep a civil tongue, or he’d knock his teeth down his throat. Dickinson’s reply to Parker was issued by way of his revolver, inspiring a rejoinder delivered from a shotgun wielded by one of Parker’s associates. Dickinson fell, but he would survive. The posse opened fire on the home, but was very quickly swarmed by the militia. Gorsuch’s other son, Joshua, was beaten bloody, but escaped, along with the rest of their raiding party– save one. The Deputy Marshal himself proved to be the only fatality.

It’s quite likely that several of Gorsuch’s accomplices in the attempted abduction would also have been killed, if not for the intervention of Lewis and Hanway, the two abolitionists they had threatened with arrest. Adamantly opposed to slavery but determined to save lives where possible, the two Quarters, at some substantial personal risk, dragged several wounded men to safety.

Within hours, tidings of the “Christiana Riot” had been dispatched throughout the country by way of telegraph, and a militarized task force composed of constables, federal marshals, and U.S. marines was deployed to comb the countryside in search of alleged co-conspirators.

“They spread out across the autumn countryside, forcing their way into the homes of blacks and whites alike, threatening anyone who was thought to have anything to do with the Underground Railroad, arresting scores of men on suspicion, with little concern for constitutional niceties,” recalls Fergus M. Bordewich in his book Bound for Canaan. “As one eyewitness put it, `blacks were hunted like partridges.’”

Parker, knowing that he and his friends faced summary execution if the joint federal-state task force found them, gathered the fugitive slaves in his protection and took them, by way of the underground, to Rochester, New York, and he eventually emigrated to Canada.

In the U.S., where the Fugitive Slave Act had effectively nationalized the practice of chattel slavery, Parker was wanted for murder and “treason” for defending the right to self-ownership. In Canada, he and other black refugees could vote, own property, and enjoy due process protections on equal terms with Canadians of any other ethnic background.

Acting on the assumption that the blacks who repelled Gorsuch and his posse at Christiana were acting under the pernicious influence of white seditionists, the administration of Millard Fillmore arranged the indictment of 38 people for “levying war against the United States.” This would have been the largest treason trial in American history, and the prosecution intended that it would put down the growing rebellion against the Fugitive Slave Law.

Resistance to that act was widespread in the northern states, several of which enacted “personal liberty laws” that nullified enforcement of the federal measure within their respective jurisdictions. This development prompted southern defenders of slavery – who just a few years later would invoke the heritage of 1776 to justify secession – to condemn as traitors those who undermined the sacred and imperishable Union. They had an ally in arch-unionist Massachusetts Senator Daniel Webster.

“If men get together and combine, and resolve that they will oppose a law of the government, not in any one case, but in all cases; if they resolve to resist the law, whoever may be attempted to be made subject of it, and carry that purpose into effect, by refusing the application of the law in any one case, either by force of arms or force of numbers – that, sir, is treason,” bloviated Webster in a speech shortly before the trial. Other elite voices were raised for the holy purpose of rebuking those whose public utterances and active resistance imperiled the rule of law.

Senator John Bell of Tennessee discerned “a fanaticism of liberty as well as a fanaticism of religion” among opponents of the Fugitive Slave Act, whom he accused of undermining “the best system of laws ever devised by man.” Whig Senator Joseph R. Underwood of Kentucky rebuked what he called the “arrogance and folly” of those who condemned “the legislation of the majority, and … threaten[ed] resistance and defiance in consequence of an alleged conflict with the law of God.” Whatever moral compunctions people had regarding slavery, Underwood maintained, “It is a duty to submit to the powers that be, and to render unto Caesar the things which are Caesar’s” – which in this case meant facilitating the rendition of black people into the custody of “owners” to whom their “service was due.” Even if the Fugitive Slave Act and similar measures were considered iniquitous, “until repealed, they must be obeyed, or it is the end of government.”

The indictment against the Christiana defendants asserted that they “did traitorously assemble and combine against the United States” for the purpose of preventing “by means of intimidation and violence the execution of the said laws of the United States.”

In December 1851, Hanway became the first to stand trial. His role in the events at Christiana was peripheral, but “the federal government felt that it had to convict a white man to avenge Gorsuch’s death in the eyes of Southerners,” explains Bordewich. That ambition was thwarted when the jury took all of fifteen minutes to acquit the pacifistic miller of all charges. The Fillmore administration made a desultory effort to prosecute other defendants during its final year.

After Franklin Pierce assumed office in March 1853, he dismissed the case – but not the effort to enforce the Fugitive Slave Law. In 1854, Pierce deployed 1,600 troops to Boston in order to take into custody a man named Anthony Burns, who had escaped bondage in Virginia. Local abolitionists had liberated Burns from the custody of Deputy US Marshal James Batchelder, who was killed in the line of duty by citizens acting in the righteous defense of the life of an innocent man.

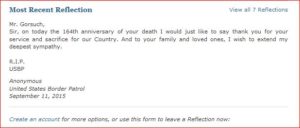

The names of both James Batchelder and Edward Gorsuch are inscribed on the honor (if that word applies) roll of US law enforcement officers killed in the line of duty. On September 11, 2015, Gorsuch received a heartfelt tribute from a fellow law enforcement officer.

“Sir, on today[,] the 164th anniversary of your death[,] I would just like to say thank you for your service and sacrifice to our Country,” wrote an anonymous member of the US Border Patrol in the “reflections” section of the Officer Down Memorial Page, which is devoted to “Remembering All of Law Enforcement’s Heroes.”

All law enforcement officers, we are insistently told, are “heroes,” even when enforcing government edicts that are morally unsupportable. Members of that fraternity of state-licensed violence regard the detestable likes of Batchelder and Gorsuch as their kin. This is one of the few instances where we should take them at their word.