This is reprinted from Jim Bovard’s blog and expands on a post originally from 2023.

Today is the 163th anniversary of the battle of Front Royal, Virginia (the town near where I was raised). On May 23, 1862, almost all the Yankee soldiers in Front Royal were captured, killed or wounded during a surprise attack by Jackson’s “foot calvary.” Both sides fought valiantly, but the northerners were greatly outnumbered. Their commander, Col. John Reese Kenly, was my great-great-uncle and the source of the first name that my father hated. According to the Civil War historical marker by the courthouse in Front Royal, Col. Kenly was mortally wounded in the battle. In reality, he was badly wounded and captured. After he was exchanged for a Confederate POW, he rose to the rank of Major General.

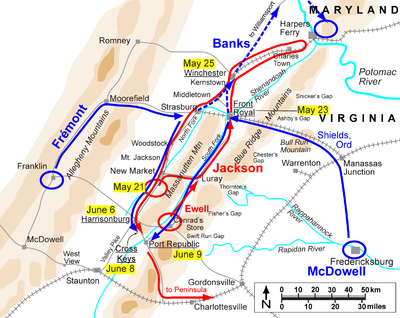

Jackson’s victory may have saved Richmond, since it spooked Lincoln into canceling plans to send 40,000 reinforcements to the Army of the Potomac, which had penetrated to the outskirts of the Confederate capital.

The best thumbnail summary of the battle I found was on Wikipedia. (Most other accounts were tangled or semi-obscure).

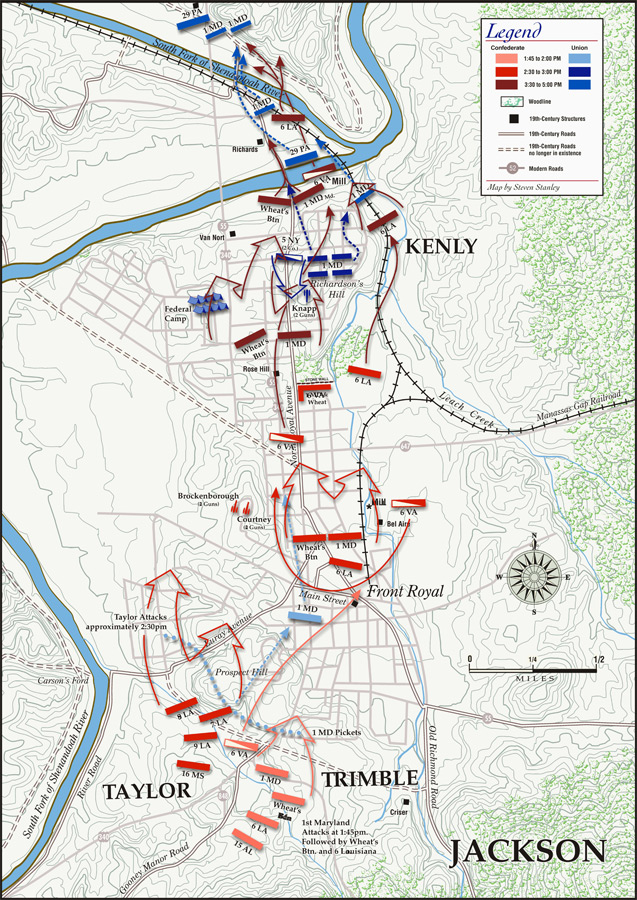

Early on May 23, Turner Ashby and a detachment of cavalry forded the South Fork of the Shenandoah River and rode northwest to capture a Union depot and railroad trestle at Buckton Station. Two companies of Union infantry defended the structures briefly, but the Confederates prevailed and burned the building, tore up railroad track, and cut the telegraph wires, isolating Front Royal from Banks at Strasburg. Meanwhile, Jackson led his infantry on a detour over a path named Gooney Manor Road to skirt the reach of Federal guns on his approach to Front Royal. From a ridge south of town, Jackson observed that the Federals were camped near the confluence of the South and North Forks and that they would have to cross two bridges in order to escape from his pending attack.

A detachment of 250 Confederate cavalry under Col. Thomas S. Flournoy of the 6th Virginia Cavalry arrived at that moment and Jackson set them off in pursuit of Kenly. The retreating Union troops were forced to halt and make a stand at Cedarville. Although the cavalrymen were outnumbered three to one, they charged the Union line, which broke but reformed. A second charge routed the Union detachment. The results of the battle were lopsided. Union casualties were 773, of which 691 were captured. Confederate losses were 36 killed and wounded. Jackson’s men captured about $300,000 of Federal supplies; Banks soon became known as “Commissary Banks” to the Confederates because of the many provisions they won from him during the campaign. Banks initially resisted the advice of his staff to withdraw, assuming the events at Front Royal were merely a diversion. As he came to realize that his position had been turned, at about 3 a.m. he ordered his sick and wounded to be sent from Strasburg to Winchester and his infantry began to march midmorning on May 24.

The most significant after effect of Banks’s minor loss at Front Royal was a decision by Abraham Lincoln to redirect 20,000 men from the corps of Maj. Gen. Irvin McDowell to the Valley from their intended mission to reinforce George B. McClellan on the Peninsula. At 4 p.m. on May 24, he telegraphed to McClellan, “In consequence of General Banks’s critical position I have been compelled to suspend General McDowell’s movements to you. The enemy are making a desperate push upon Harper’s Ferry, and we are trying to throw Frémont’s force and part of McDowell’s in their rear.”

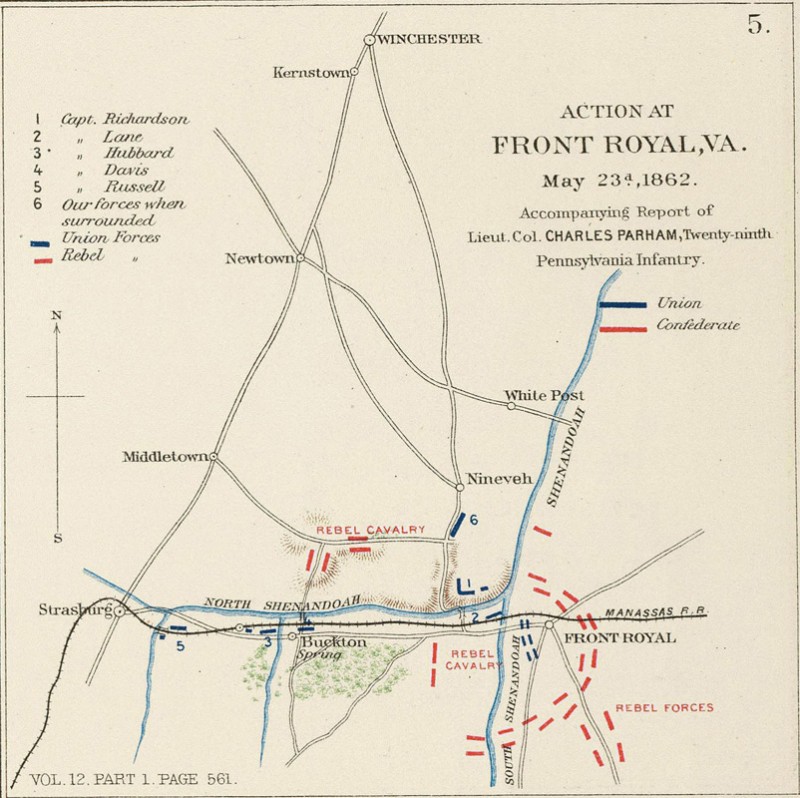

Here are a couple maps illustrating the day’s fighting:

The National Park Service did a nice analysis comparing the 1862 battlefield to the modern layout of the town and area.

The New York Times, in an excellent recent online article entitled “Stonewall in the Valley,” captured the dynamics preceding Jackson’s surprise attack at Front Royal:

Jackson’s small army faced immediate challenges to the north and west: Banks’s main force of 19,000 men was to the north at Harrisonburg, while Frémont had 20,000 men only 35 miles to the west of Banks’s encampment. But the Union generals lacked Jackson’s tactical genius,

still celebrated today, which rested on two maxims: “Always mystify, mislead, and surprise the enemy” and “never fight against heavy odds” if you can “hurl your own force on” the “weakest part of your enemy and crush it.”Jackson put both strategies to use in the valley. Confederate reconnaissance made sure he always knew where his opponents were, but his whereabouts very often proved a mystery to them. On April 28, for instance, Banks assured his superiors that “Our force is entirely secure here. The enemy is in no condition for offensive movements. … I think we are now just in condition to do all you can desire of us in the valley — clear the enemy out permanently.” Two days later Banks wrote again, saying he had more or less scared Stonewall away: “Jackson is bound for Richmond. This is the fact, I have no doubt.”

Jackson and his troops were indeed in motion, but not toward Richmond. On April 30, Jackson set his men marching south from their position in the Elk Run Valley. Spring rains had created a quagmire, trapping his troops in an exhausting, muddy hell. It took them two days to travel 16 miles to Port Republic.

Thinking quickly, Jackson resorted to the sort of maneuver that confounded his enemies and just as often surprised his own troops. “Heaven only knows where he is bound for now,” recorded one Confederate infantryman in his diary. “I know that ninety-nine out a hundred of his men have no more idea of where they will turn up than the buttons in their coats.” Jackson turned his troops to the east and marched through Brown’s Gap to Mechum’s River Station on the Virginia Central Railroad. Once there he loaded his weary and disheartened troops, who thought they were abandoning the valley to the Union forces, onto trains and moved them west to Staunton, the strategically positioned southern anchor of the Shenandoah Valley. “We are retiring and advancing at the same time,” wrote another of Jackson’s men, “a condition an army never undertook before.” A few days later, Jackson won his unexpected victory at McDowell.

The Confederate force’s weeklong slog from the Elk Run Valley to Staunton, while uncharacteristically slow, was a testament to the endurance of Jackson’s “foot cavalry,” who had quickly gained a reputation for showing up where least expected, thereby gaining a psychological edge that often offset the superior numbers enjoyed by the Union army. Jackson’s troops marched 177 miles during a single 17-day period in mid-May, for example, and in the third week of May alone covered up to 30 miles a day in their successful effort to deceive Banks’s forces at Front Royal, toward the northern end of the Shenandoah Valley.

This map illustrates the campaign discussed above:

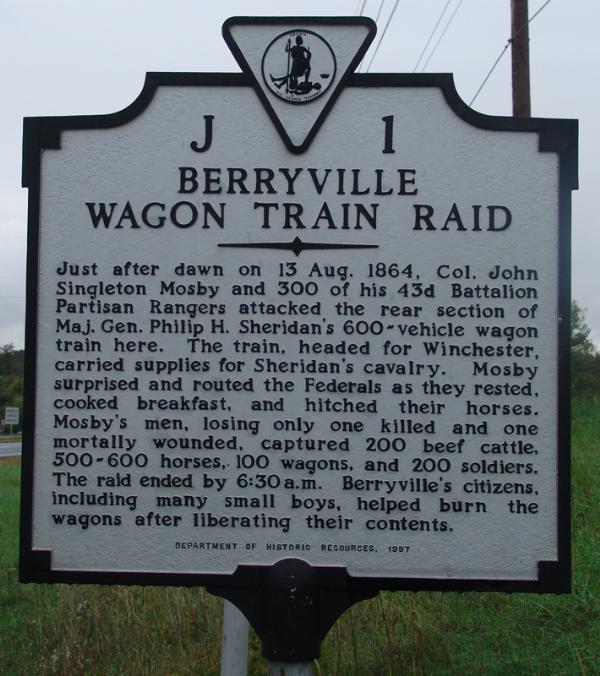

The war became uglier as the years passed. In 1864, Gen. Sheridan’s troops sought to starve the civilian population into submission by burning all the crops, barns, and many of the houses in Warren County and elsewhere in the Shenandoah Valley. Such policies helped explain why Warren County’s population fell by 20% in the 1860s. Gen. John Reese Kenly was one of the Union commanders guarding a massive wagon train of supplies to Sheridan’s Union Army in Winchester in August 1864. After John S. Mosby’s Confederate Rangers launched a surprise attack and captured most of the wagons, Kenly was transferred to the Maryland eastern shore for the rest of the war.

Here is Col. John S. Mosby’s summary of that wagon train raid from his memoirs:

Sheridan was obviously greatly solicitous about preserving his communications, for he knew that they were weak and a vital necessity for his army He evidently had some information which increased his anxiety about his rear. One night, when his headquarters were at Berryville, I sent my best scout, John Russell, with two or three men, to reconnoitre, intending to deliver a blow at Sheridan’s rear and thus cripple him by cutting off his supplies. John reported long trains passing down along the valley pike. I started for the vicinity with some 250 men and two howitzers, one of which became an encumbrance by breaking down. Through Snicker’s Gap we crossed the Blue Ridge Mountains after sundown and passed over the Shenandoah River not far from Berryville. I halted at a barn for a good rest and sent Russell to see what was going on upon the pike. I was asleep when he returned with the news that a very large train was just passing along. The men sprang to their saddles. With Russell and some others I went on in advance to choose the best place for attack, directing Captain William Chapman to bring on the command. About sunrise we were on a knoll from

which we could get a good view of a great train of wagons moving along the road and a large drove of cattle with the train. The train was within a hundred yards of us, strongly guarded, but with flankers out. We were obscured by the mist, and, if noticed at all, were doubtless thought to be friends. I sent Russell to hurry up Chapman, who soon arrived. The howitzer was made ready. Richards, with his squadron, was sent to attack the front; William Chapman and Glasscock were to attack them in the rear, while Sam Chapman was kept near me and the howitzer.

My scheme was nearly ruined by a ludicrous incident, the fun of which is more apparent now than it was then. The howitzer was unlimbered over a yellow-jacket’s nest. When one of the men had rescued the howitzer, a shell was sent screaming among the wagons, beheading a mule. The shot was like thunder from a clear sky, and the mist added to the enemy’s perplexity. This shot was our signal to charge, and we met little resistance. Panic reigned along their line, and I only lost two men killed and three wounded. Before the fighting ended, as I knew that the guard would soon recover from the panic, I had men unhitching mules, burning wagons, and hurrying prisoners and spoils to the rear. There were 325 wagons, guarded by Kenly’s brigade and a large force of cavalry. They had not stopped to find out our numbers. We set a paymaster’s wagon on fire, which contained – this we did not know at the time – $125,000. I deployed skirmishers as a mask, until my command, the prisoners, and booty were well across the Shenandoah River. We took between 500 and 600 horses, 200 beeves, and many useful stores; destroyed seventy-five loaded wagons, and carried off 200 prisoners, including seven officers.

If anybody has good sources or good links on the 1862 battle, please add them to the Comment Section.

Photo of the marker for Kenly’s Last Stand