Sunday, June 13, 2010

Amnesty for the Banksters, Debtor’s Prison for the Serfs

In 2002, Nusbaum grew weary of robbing people on behalf of the state. Rather than repenting in sackcloth and ashes, as any decent person would, he hired out as a privateer — a freelance buyer and collector of tax debts.

This form of retail fascism — a public-private partnership in plunder — was immensely profitable for Nusbaum. Had he exercised even the slightest restraint on his corrupt appetite, Nusbaum most likely wouldn’t be headed for prison.

Maryland is one of 29 states that permit city governments to raise money by selling tax debts to investors. Each year, Baltimore’s municipal government bundles up tax liens against properties whose owners haven’t paid local taxes or utility bills (such as water and sewage fees) and sells them at auction.

In the most recent auction, Baltimore sold liens on 12,689 properties — ranging from rotting shells of long-abandoned homes to office buildings in the downtown business district. Purchasers assume responsibility for collecting the debts, and the opportunity to foreclose on properties whose owners can’t pay them off.

According to a study conducted by the Baltimore Sun, twenty percent of those liens involved amounts smaller than $1,000. Financial necromancers employed by collection agencies can transmute a trivial amount — a delinquent utility bill or an unpaid and long-forgotten municipal citation — into a budget-crippling debt of several thousand dollars.

“You will pay,” one of Nusbaum’s minions told a victim who called to complain after a tiny unpaid water bill had metastasized into a $4,000 extortion demand. “Everybody does.”

Nusbaum and his cronies filed over 6,000 lawsuits, raking in an estimated $11.5 million in legal fees, title search fees, and interest. This inevitably attracted the attention of the “Justice” Department’s antitrust division, which discovered that Nusbaum, his partner Jack W. Stollof, and other as-yet unnamed investors engaged in collusive bidding in a dozen tax auctions conducted in Baltimore and five other Maryland jurisdictions.

According to federal prosecutors, the actions of Nusbaum and his colleagues were a criminal conspiracy to violate the Sherman Antitrust Act. Once in possession of the liens, the conspirators “used the court system to threaten homeowners with seizure of their properties unless they paid legal fees, interest, and other charges … [that] often totaled 10 times the original debt,” observed the Sun.

The real crime here, according to the Feds, was not the use of government-aided extortion to wring hugely inflated sums from struggling, debt-plagued citizens, but rather the use of collusion to enhance the cabal’s profits at the expense of local governments. You see, the entire point of the tax auction racket, in the Sun‘s eminently suitable phrase, is “feeding the public treasury.”

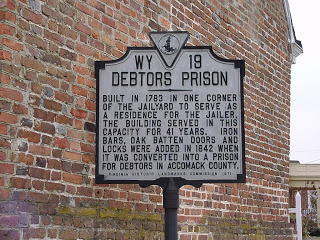

|

| Ancient artifact, or foreshadowing of the future? |

During a rigged auction in 2006, Nusbaum and his comrades bought a bundle of liens containing Vicki Valentine’s unpaid $362 municipal water bill.

Valentine had inherited a home in West Baltimore from her father, who died, after a long struggle with Alzheimer’s, in 2003. The house was free and clear, but many of the utility bills had been left unpaid.

Struggling with chronic depression after taking care of her dying father, Vicki was soon dealing with unemployment as well. In 2006, Vicki he paid $100 on an outstanding water bill of $462.28. By year’s end, that figure shot up to more than $700, after the city added interest, processing charges, and property taxes.

Under severe financial strain, Vicki filed several legal challenges, which delighted the firm that had purchased the lien, since this permitted them to tack on additional legal costs. On September 19, 2008, a judge ordered Vicki to pay $3,603.41, or lose a home that was already bought and paid for. She didn’t have the money. So last February, the local sheriff’s department seized Vicki’s home on behalf of Montego Bay Properties, the entity that held the lien following at least two post-auction transfers of ownership.

In a desperate letter written a year before her house was seized, Vicki pleaded with Baltimore City Circuit Court to extend the payment period.

“For now, this is the roof over my son’s and my head,” she observed, pointing out that she was unemployed and frantically looking for work. “I am trying to get the money together to catch up on my delinquent bills. Please allow more time to pay all bills connected with the foreclosure….”

Vicki didn’t understand that in the corporate socialist system that now exists, mercy is a gift conferred only on the powerful and politically connected. This is illustrated by the fact that the presiding officers of DRT Fund, which was listed as a co-conspirator in Nusbaum’s bid-rigging scheme, were granted amnesty — that is, official forgiveness — in exchange for admitting that they had done wrong and facile promises to pay restitution “to any person or entity injured as a result of the bid-rigging activity … in which [the investment firm] was a participant.”

Here’s the curious thing about that promise of “restitution”: The only party “injured” by the bid-rigging scheme, according to the Feds, was the Municipal Government of Baltimore.

The specific terms of the settlement remained sealed, and DRT Fund’s owners aren’t discussing the particulars in public. However, we can be sure that Vicki Valentine isn’t listed among those “injured” by DRT, whose co-owners, Anthony De Laurentis and John Rieff, are now in possession of her home.

Two years ago, Milwaukee resident Peter Tubic nearly lost his home to foreclosure as a result of an unpaid $50 citation for parking an inoperable van on his own property. A government that arrogates to itself the supposed authority to regulate such matters won’t scruple to add extortionate penalties to the original citation; thus it’s not surprising that the City of Milwaukee eventually demanded $2,645 from Tubic as ransom to prevent the seizure of his home. Eventually a local judge succumbed to an unprofessional fit of common sense and dismissed the citation outright.

Confiscation of a home to collect small debts remains uncommon. However, “people are routinely being thrown in jail for failing to pay debts,” reports the Minneapolis Star-Tribune. As is the case in Arizona, Arkansas, Indiana, Illinois, and other states, the Land of 10,000 Lakes is infested with agents of “well-funded, aggressive and centralized collection firms, in many cases run by attorneys, that buy up unpaid debt and use the courts to collect.”

As a result, it’s increasingly common for people who owe small amounts to find themselves being confronted by police — in the streets, at home or work, while driving, or even while recovering from surgery — and hauled away in handcuffs. Warrants have been issued over outstanding debts as small as $85, which is “less than half the cost of housing an inmate overnight.”

After a brief but robustly unpleasant interlude behind bars, debtors are brought before a judge and compelled to sign documents permitting the collection firms to garnish their wages or extract money from their bank accounts. Refusal can lead to a “indefinite incarceration,” a sentence recently imposed, without trial, on a debtor from Kenney, Illinois. “Bail” consists of paying the amount demanded by the collection firm, which is the amount of the purchased debt plus whatever enhancements the firm can devise.

“A firm aims to collect at least twice what it paid for the debt to cover costs,” points out the Star-Tribune. “Anything beyond that is profit.” Successful debt-buying firms enjoy very impressive profit margins. Portfolio Recovery Associates, a Virginia debt buyer, reported a 16 percent net margin last year; for Encore Capital Group of San Diego, last year brought a 10 percent net profit. By way of contrast, Wal-Mart’s profit margin last year was 3.5 percent.

The “distressed receivables” market is immense, and bundled debts are constantly repackaged and re-sold. It’s quite common for people to be contacted by multiple collection agencies demanding payment on the same long-forgotten debt, which may have been sold and repackaged several times after being written off by the original creditor.

Ohio-based Unifund CCR Partners, one of the most aggressive debt-buying firms, “feasts on the famine of others,” explained a 2003 profile of its founder, Turkish-born David Rosenberg, in the Cincinnati Enquirer.

Unifund, which serves clients such as Citibank, “isn’t in the embarrassment business,” insisted Rosenberg seven years ago. Either there are odd gaps in Rosenberg’s vocabulary or his priorities have changed: Today, Unifund routinely seeks arrest warrants for those unable or unwilling to pay off old debts.

Rosenberg created Unifund as a 20-year-old high school dropout in 1986. Originally the company bought and collected on bad checks written to supermarkets. The company paid 75-80 percent of the dollar value of each check, and reaped 115-125 percent of its face value by imposing insufficient-funds fees.

As bank failures accumulated in the late 1980s, Unifund began to buy and collect on batches of bad bank loans sold by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation for pennies on the dollar. By 1990 it had sufficient capital to buy up a series of bad debt portfolios from Manufacturers Hanover Trust with face values of up to $50 million apiece, according to the Enquirer.

Rosenberg, who profited handsomely on the debts of others, is no stranger to bad debt himself. “Over the past decade,” reported the Enquirer in 2003, “Rosenberg’s name has appeared on Ohio income tax liens, an overdue notice for Vermont real estate tax, and a lawsuit for an unpaid auto loan.”

Unlike many of his victims, Rosenberg has never felt the cold steel of handcuffs biting into his wrists. Given the pervasive perversity of our times it doesn’t come as a surprise that Unifund, which is able so suborn police and courts into doing its bidding, is a criminal enterprise.

During the past decade, Unifund has settled several class-action lawsuits asserting that the firm routinely engages in illegal practices — such as imposing bogus legal fees and collecting on debts beyond the statute of limitations. In one settlement, Unifund was forced to pay Queens resident Jose Luis Muniz an undisclosed sum after it fraudulently attempted to collect on a $21,000 credit card debt Muniz had paid off ten years earlier.

|

||

| Rosenberg goes clubbing with Hip-Hop mogul Russell Simmons and celebrity trollop Kim Kardashian. |

Suits filed in Texas and Illinois claimed that Unifund defrauded credit reporting agencies by “freshening up” credit card delinquency dates on old debts the firm had purchased.

The Fair Credit Reporting Act requires that delinquent credit card accounts be expunged after seven years of dormancy. Plaintiffs accused Unifund of “rolling back to odometer” on the debts they had purchased by moving up the delinquency dates by as much as six years. This damaged the credit ratings of the victims and made them vulnerable to the other abusive collection practices in Unifund’s arsenal.

In the mid-1990s, Unifund was bought by ZB Limited Partners. “ZB” refers to the Zises Brothers — Jay, Seymour, and Selig. In the mid-1980s, the Zises Brothers created an immense pyramid scheme-cum-tax shelter called Integrated Resources, which funded its operations by issuing high-yield or “junk” bonds.

|

| Seymour Zises (left) at a 2008 social function. |

In early 1989, the brothers “managed to sell most of their holdings at $21 a share — far above the market price — to the ICH Corporation, a highly leveraged insurance company,” observed the New York Times.

The company defaulted on its bonds and commercial notes in June 1989. A few years later, the Zises Brothers — who cultivated some very useful political ties with the neo-conservative establishment — reached a settlement in which they were permitted to pay their creditors a small fraction of what they owed.

The brothers had enough cash on hand to buy Unifund and get involved in several other ventures, such as Family Management Corporation — an investment firm that reportedly funneled millions of dollars into Bernie Madoff’s Ponzi scheme.

It’s not likely that the Zises Brothers are haunted by the thought that the investors whose money they’ve pissed away will someday arrange for them to be arrested and humiliated in front of their friends, families, and children.

Unifund is just one of dozens or scores of similar firms that are flourishing in the aftermath of the debt bubble’s collapse. The mechanism at work here is the mirror image of the one that operated while the bubble was being inflated.

In the early 2000s, with the Federal Reserve pumping huge amounts of “liquidity” into the economy, it was immensely profitable for lenders to entice borrowers of dubious credit-worthiness into mortgages and other loans they weren’t really able to pay. Before the collapse, bundling and re-selling bad debts to investment banks was a lucrative enterprise for Goldman Sachs and other major powers on Wall Street. Now that the bubble has burst, the titans of Wall Street are bailed out by the same taxpayers who often face the prospect of arrest and incarceration for their own bad debts.

The welfare queens of Wall Street, cushioned by subsidizes extracted from taxpayers at gunpoint, are ill-disposed to liquidate bad debts through negotiation. This helps explain why an increasing number of people who find themselves “upside down” on their home mortgages are practicing “strategic default”: With lenders unwilling to negotiate reasonable terms, the debtors simply stop making payments. This has inspired Wall Street’s tax-subsidized deadbeats to begin a PR campaign to demonize “ruthless borrowers” as uniquely depraved.

“Having been deadbeats and strategic defaulters of the first order,” writes economic analyst Yves Smith, the major banks “continue to manifest their characteristic unmitigated gall [by] hectoring the public about honorable behavior.” Smith predicts that ere long we will witness the return of debtor’s prison, which was supposedly abolished in the 19th century.

A cynic once said that while a petty thief will find himself behind bars or dangling from the end of a rope, the most powerful criminals are those who run the jails and operate the gallows. The corporatist plutocracy controlling our country is determined to make a prophet of that anonymous cynic.

|

| Dum spiro, pugno! |

Content retrieved from: http://freedominourtime.blogspot.com/2010/06/amnesty-for-banksters-debtors-prison.html.