Tuesday, May 12, 2009

Criminalizing Citizen Activism: The Chris Pentico Case

Who owns this joint? The Borah Building in downtown Boise provides temporary office space for Governor Butch Otter, who — as a state employee — doesn’t actually own the building, nor does he pay the rent. So by what supposed right does the Governor, or any of his lickspittles, file a “trespassing” complaint against one of the citizens who do own that property?

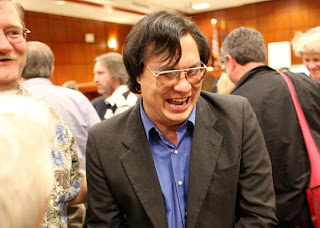

Chris Pentico, a quiet, self-possessed 42-year-old resident of Mountain Home, Idaho, has a disposition as mild as tapioca. Yet the description offered by a state prosecutor at his sentencing hearing today (May 11) would lead you to believe that beneath his docile exterior, Mr. Pentico — who looks a bit like a younger, clean-shaven, presentable version of Hank Willams, Jr. — is a churning urn of burning rage.

Years ago, recited the prosecutor in the adolescent whine typical of a law school graduate of recent vintage, Mr. Pentico was “involved in an incident” on campus at Boise State University in which he displayed his “belligerent” personality. This is why he wound up “on law enforcement’s radar” — even though, as we would later find out, no charges were filed, and Pentico’s record remained unsullied.

As a political activist with the Idaho Republican Party, Pentico frequently met with members of the state legislature and other public officials, often to complain about irregularities and examples of what he considers to be public corruption. This, according to our young prosecutor, made many public officials “uncomfortable.”

She considered that to be a species of crime. I consider it a respectable downpayment on the type of treatment most public officials should expect: Nearly all of them should be unemployed, and those who remain on the public payroll should always be wearing the same facial expression that occupied the features of those invited to dine at the table of Dionysius of Syracuse — immediately beneath the Sword of Damocles.

Pentico was viewed as a “potential threat,” a “problem subject,” a “dangerous individual” prone to “harassing-type behavior,” continued the prosecutor. “Due to his own conduct, he made himself something of a target” for law enforcement,” she insisted. “And then he set his sights on the governor.”

From this description one would be entitled to assume that Pentico was a suicide bomber in training, or perhaps had been discovered setting up a sniper’s nest in a book depository somewhere overlooking Governor Otter’s familiar travel route. What else could be meant by the frantic accusation that Pentico was “setting his sights” on the Gem State’s imperiled Chief Executive?

Well … would you believe, he tried to hand-deliver a letter.

Not a letter bomb, mind you, nor an envelope containing anthrax, or even a threat of some variety.

Pentico’s letter contained a complaint about an attempt to ban him from contacting state legislators with complaints and civic requests of various kinds. Pentico delivered his letter to the governor’s office at the Borah Building on April 2, 2008.

A week earlier, he had beentold by an Idaho State Police Officer that “my presence made a few of the legislators nervous” — and of course, we can’t have that.

Pentico was told that he was “not welcome in the Capitol Annex,” a public facility intended to provide public access to state legislators who supposedly represent that same public.

While the first officer was addressing Pentico, he was joined by another policeman whom Pentico originally identified as Officer Pettis. The second officer expanded the compass of the public territory from which Pentico was to be banished.

“Officer Pettis said I was not welcome at the State Board of Education’s offices [despite the fact that ] I have not been there in years…. Then he added `I was not welcome on the third and fourth floors of the Borah building; this is where the Governor’s offices are located.’ Officer Pettis … also added `Do not contact legislators’ and `Do not e-mail them.’ He also gave me the implication problems woul d occur for me if I did. There is no written notification or anything of that nature.” “I have not threatened anyone,” Pentico continued.

“I believe there has been a pretty clear breach of law here. I am also under the impression that Officer Pettis willfully carried out an unlawful order. I want to know the authorization and jurisdiction for these orders. I also consider it inexcusable to use law enforcement to intimidate law-abiding citizens to not contact with their elected officials.”

Pentico delivered that letter to the Governor’s office on April 2, politely asked about an appointment, and left — no doubt cleaving a huge trail of raw, visceral terror in his wake. As Pentico left the Borah Building, he was overtaken by the same ISP officer who had issued such expansive warnings the previous week — Corporal Jens Pattis (not “Pettis,” as spelled in Pentico’s letter).

Out of what the Judge was told was concern for “officer safety,” Pentico was handcuffed in public view for about twenty minutes and then issued a citation for “trespassing.” Two matters arise for discussion here. First of all, Pentico was a threat to nobody, and handcuffing him was an entirely gratuitous assault on his person.

Interviewed by Wayne Hoffman of the Idaho Freedom Foundation, Corporal Pattis insisted that Pentico alone was to blame for this indignity, since he had “defied a law enforcement order” to avoid the Borah Building. Pattis is part of the New Model Army of law enforcement — a corps trained to believe that citizens have an unqualified duty to obey every directive emanating from the tax-devouring gullet of someone in a state-issued costume.

Corporal Pattis had no authority to dictate the terms on which a peaceful, law-abiding citizen could petition his representatives. “I bent over backwards for this guy, trying to help him out,” insists Pattis.

I’ll warrant that he certainly bent over for somebody.

The second issue here is the trespassing charge itself. At no time during the prosecution of Chris Pentico was the identity of the complainant specified; indeed, great care seems to have been taken to avoid identifying the person who turned to Pattis and — slapping a palm to his thigh and emitting a quick whistle — yelled, “Sic ‘im!”

This omission is critical for at least two reasons.

First, Mr. Pentico was not permitted to face his accuser; second, without an actual accuser, it was impossible to satisfy the legal requirement that Pattis be acting as the authorized agent of the owner of the property on which Pentico was supposedly trespassing.

The Idaho State Code, Title 18-7008(8), defines the crime of willful trespass as one committed when a person “except under landlord-tenant relationship, who, being first notified in writing, or verbally by the owner or authorized agent of the owner of real property, to immediately depart from the same and who refuses to so depart, or who, without permission or invitation, returns and enters said property within a year, after being so notified….”

In Pentico’s case, the prosecution claimed that the “order” issued by Pattis on March 25 constituted a notification by the “authorized agent of the owner” of the Borah Building to avoid the premises in question, presumably for a year. Pentico waived a jury trial.

The trial judge, Ada County Magistrate Kevin Swain, insisted that because the trespassing statute did not distinguish between public and private property, it must apply to both. In reaching that conclusion, however, His Honor failed to explain how the tenant of a publicly owned property can order the eviction of an owner of the same.

As someone who believes the phrase “government-owned property” to be an oxymoron at best and an obscenity in every case, I offer the foregoing only to underscore the grotesque and obvious illogic of using the trespassing statute in this case.

Certainly, if Mr. Pentico’s presence inspired a reasonable fear for the physical safety of the governor or any of his staff, he could be forcibly removed and, if appropriate, cited or otherwise made subject to punishment. He did nothing of the sort.

But unless the trespassing law is to be read in such a fashion that it would permit tenants to evict landlords, its application to this case makes no sense. This is underscored by the lack of an actual accuser and putative victim in this matter.

Who was injured by Pentico’s purported act of trespass, and what form did that injury take? Idaho State Police Lt. Col. Kevin Johnson told the Idaho Statesman that Pentico had been banned from the Borah Building pursuant “at the request of the governor’s office.”

But the “office” — meaning the tax-fattened claque who “works” in the physical offices in question — does not own that building. When that administration leaves, new tenants will arrive and make similarly disastrous use of those facilities. But they are owned by the public. If the public owns the property, a member of the public cannot trespass on it.

Furthermore, far from acting as the “authorized agent” of the owner(s), Corporal Pattis was illegally attempting to expropriate one of the actual owners; it is as if he had handcuffed a landlord who strode up to the front door of a residential property he owned to slip a “past due” notice into the tenant’s mail slot.

From the prosecution’s perspective, the injury inflicted by Pentico when he quietly delivered a letter to the governor’s staff must have been quite severe. They recommended that he be hit with a $500 fine (plus court costs), a 90-day jail sentence, and 2 years of unsupervised probation.

After painting a portrait of Pentico as an incorrigible recidivist offender deserving of stern treatment, the bright young lady representing the prosecution — who was apparently tone-deaf to her own contradictions — depicted the foregoing terms as the product of leniency that took into account the fact that Pentico “really hasn’t been in any trouble before this.”

Then just what the hell was the whole point of this?

In issuing his sentence, Judge Swain — to his credit — immediately dispelled the suffocating cloud of flatulent insinuations emitted by the prosecutor (whose name I’m deliberately omitting in the hope that she will grow up and do something useful with her life) regarding Pentico’s supposedly criminal nature. This reflected, in part, the influence of State Rep. Pete Nielsen, a Republican who brought with him a letter signed by several other members of the state legislature.

Those paladins of the public weal were not so palsied with terror by the very thought of the fearsome Chris Pentico that they couldn’t affix their signature to a letter attesting to Pentico’s decency and civic-mindedness.

Judge Swain is up for reelection this year. I trust that he was alert to the presence in the courtroom of scores of well-mannered but attentive activists who would do everything they could to ensure his return to the private sector should he inflict an onerous sentence on Pentico.

Swain outlined what he called the four objectives of sentencing: punishment, deterrence, restitution, and rehabilitation. He quite sensibly said that the final three considerations didn’t apply to Mr. Pentico, who had injured nobody and done nothing to merit punishment, let alone to display a need for rehabilitation.

Pentico was in “technical” violation of the trespassing statute, Swain insisted (incorrectly, as we’ve seen), but his offense was de minimis. Besides, his entire purpose was to exercise a function of citizenship that should be encouraged — he was petitioning a representative for redress of grievances.

Owing to the nature of the “offense” and the obvious decency of the “offender,” Swain dispensed entirely with the prospect of jail time or fines. He imposed a term of 30 days of unsupervised probation and a withheld sentence, the latter of which would be lifted and expunged from Pentico’s record “when — not if — you finish probation successfully, as I’m sure you will,” Swain explained.

A wave of relief and a ripple of applause coursed through the courtroom. Delighted as I was to hear Judge Swain summarily dismiss the prosecution’s caricature, I didn’t join in the applause, nor did a couple of other people who had come to support Pentico.

The problem here is that a man who did nothing wrong was convicted — albeit in ephemeral fashion — of a crime by a legal positivist judge. Sure, Judge Swain — a well-spoken and personable figure — did what he could to minimize the impact of that conviction.

But he still found a way to validate the idea that the state (in this case represented by the oddly amorphous entity called the “governor’s office”) has “rights” that trump those of citizens, and that the cold steel of handcuffs biting into one’s wrists is a suitable reward for those who “defy” patently illegal “orders” from the state’s armed enforcers.

Judge Swain’s sentence was greeted with cathartic relief and left Pentico’s friends with a sense that a partial victory, at least, had been won. Granted, clear-cut victories for individual liberty are are rare as pity from Stalin, or insight from Sean Hannity.

But now that it’s clear Chris Pentico won’t suffer further punishment for doing nothing wrong, his friends and supporters should take a long, sober look at exactly what was “won” in this case, and by whom.

I mean no insult, either overt or implied, to the wonderful people who had gathered in support of Chris Pentico when I say that the applause at the end of the trial prompted me to recall Gibbon’s observation: “A nation of slaves is always prepared to applaud the clemency of their master, who, in the abuse of absolute power, does not proceed to the last extremes of injustice and oppression.” I’m willing to assume that the applause was entirely for Chris Pentico’s courageous resolve, not for the statist judge who found a low-key way to validate the demands of Idaho’s ruling class.

Video/Podcast Extra:

Chris Pentico (along with some friends) is interviewed by former Idaho state legislator Elizabeth Allan Hodge:

***

***

Pt. II

Pt. III

Pt. IV

Pt. V

____

In my original version, written in a fog of sleep-deprivation (hey, with six kids including a newborn, sometimes I have to work well beyond the wrong side of midnight), I referred to Elizabeth Hodge as a current, rather than “former” legislator. That version also had a misfire caught and corrected by “rick” in the comments thread.

On sale now.

Dum spiro, pugno!

Content retrieved from: http://freedominourtime.blogspot.com/2009/05/criminalizing-citizen-activism-chris.html.