Monday, September 24, 2012

How to Kill a Law Enforcement Career: The Case of Regina Tasca

|

| Regina Tasca at the Borough Council meeting dealing with her termination. |

What does it take for a police officer to get fired?

Regina Tasca, a 20-year veteran officer from Bogota, New Jersey, was terminated by the Borough Council on September 21. This decision came after a lengthy investigation into her purported misdeeds.

Prior to her termination, Officer Tasca had never generated a single citizen complaint or official reprimand. She was being considered for promotion before she got in trouble in April 2011.

What horrible deed led to Officer Tasca’s dismissal?

Before answering that question, it’s worth reviewing a few recent cases of severe police misconduct that either went entirely unpunished, or resulted in sanctions short of termination.

Lawrenceville, Georgia Police Chief Randy Johnson refuses to fire Detective Tim Ashley, an abusive cop with a nasty habit of imprisoning innocent people – a habit that has already cost the local taxpayers a great deal in legal expenses. Among his victims is Ann Jaipersaud, who operates a Chevron station in Lawrenceville.

When Jaipersaud found herself dealing with an aggravated customer, she made the common – and by now inexcusable – mistake of calling the police for help. As is always the case, matters immediately got much worse after the police intervened in the dispute.

The customer, an American of African ancestry, apparently thought that the store owner (a woman of East Indian descent who was born in Guyana) didn’t want to sell him gas on account of his ethnic background. When told that the station had no gasoline, the customer — who verbally abused the store owner — refused to leave.

“He said I need to get him here now or else,” Jaipersaud recalled. “I asked him if he was threatening me…. And he said, `No, I’m arresting you.’” The officer later explained that he arrested Jaipersaud for being “disrespectful.” She spent ten hours in jail for what was later determined to be a wrongful arrest. A jury awarded Jaipersaud nearly $140,000 in damages.

|

| Detective Tim Ashley abducts Jaipersaud (right). |

Lawrenceville tax victims will almost certainly forced to indemnify Ashley’s crimes against 29-year-old Mississippi resident Carlos Fairley, who was abducted by police in a SWAT-style raid and then spent two months behind bars as a result of the detective’s culpable disregard for evidence.

|

| Well-compensated thug German Bosque. |

|

| His pension’s secure: Peters. |

In Houston, four police officers were recently suspended for engaging in a scheme to embezzle overtime pay by falsifying traffic tickets. Over the past four years, the officers had fraudulently collected almost one million dollars in overtime. One of them, Senior Officer Matthew Davis, soaked up $347,000 in 2008 alone. Davis had previously been suspended for improperly dismissing tickets at the request of a City Council member.

Davis received a 30-day unpaid suspension, as did fellow Officer Steven Running. Senior Officer Kenneth Bigger was handed a 20-day suspension. The sternest punishment – if the term could be applied here – was imposed on Sergeant Paul Terry, who was suspended for 45 days.

By any rational standard, embezzling a million dollars is a serious crime. Yet none of the officers involved in that felonious conspiracy faced criminal charges. None of them has been required to make restitution. None of them was fired.

Accordingly, it would be reasonable to expect that Regina Tasca’s firing offense would be more serious than defrauding Houston’s tax victims out of a million dollars. As it happens, her offense had nothing to do with corruption of any kind.

On September 22, a Houston Police Officer named Matthew Jacob Martin shot and killed 45-year-old Brian Claunch, a one-armed, one-legged man in a wheelchair who was “armed” with a pen. The victim was an emotionally disturbed man living in a group home for the mentally ill. The caretaker made the reliably fatal mistake of calling the police.

According to Houston PD Spokeswoman Jodi Silva, the shooting was justified because Officer Martin, who was supposedly “trapped” by Claunch, feared “for his partner’s safety and his own safety” despite the fact that they were both young, able-bodied, armed individuals confronting an invalid in a wheelchair who was armed with a writing utensil.

The killing of Brian Claunch, which was not Officer Martin’s first shooting, precipitated a huge public outcry, and the Police Chief has called for a Justice Department investigation. On previous performance it is all but certain that Martin will not be prosecuted, nor is it likely that he will suffer injury to his career.

It so happens that the incident that led to Regina Tasca’s firing offense also involved an emotionally disturbed and unarmed individual who was perceived as a threat to officer safety. Did she shoot and kill the subject, or use disproportionate force in subduing him?

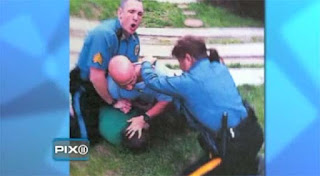

|

| Career-ending nobility: Tasca stops Rella’s assault. |

No. As the officer in charge of the situation, Tasca followed the Bogota Police Department’s use-of-force policy to the letter by intervening to protect the victim from a criminal assault committed by an officer from another department.

As Officer Tasca summarized the matter in an interview with Pro Libertate last spring: “I didn’t fail to aid another officer; I acted to stop a beatdown.” Tasca interposed herself to stop Sgt. Joe Rella’s assault on 22-year-old Kyle Sharp, an emotionally troubled young man who had done nothing to justify police violence of any kind.

About two days after the episode, Tasca was labeled a “danger” to her fellow officers and suspended by the department. Following a year of disciplinary reviews, psychological evaluations, and a spurious legal process worthy of the Soviet Union, Tasca was fired.

Tasca was on patrol on April 29, 2011 when she got a call for medical assistance. Former Bogota Council Member Tara Sharp, concerned about the erratic behavior of her son Kyle, called the police to take him to the hospital for a psychological evaluation. As noted earlier, requesting police intervention, particularly in cases of this kind, is never a good idea. Sharp was exceptionally fortunate that Officer Tasca was the first to respond: She has years of experience as an EMT and had just completed specialized training on situations involving psychologically disturbed people.

Once on the scene, Tasca acted quickly to calm down the distraught young man, whose mood changed abruptly when he saw the other officers arrive.

The official report on the matter, which was written by retired Judge Richard Donohue, claims that Kyle “was aggressive [and] started to walk away….” Only someone incurably inhospitable to both logic and honesty would describe walking away as “aggressive” behavior. Kyle also instructed the police not to step on his property, which was a lawful order the police were required to obey. Instead, Sgt. Chris Thibault tackled Kyle, wrapped him in a bear hug, and attempted to handcuff him. Within an instant, Sgt. Joe Rella piled on and began to slug Kyle in the head while his horrified mother screamed at the officers to stop.

According to Thibault, it was necessary to assault Kyle because he believed “danger is near for us if we let this kid go.”

No, really. That’s what Thibault said, under oath, during Tasca’s disciplinary hearing.

Tasca instinctively did what any legitimate peace officer would do: She intervened to protect the victim, pulling Rella off the helpless and battered young man. Tasca’s act was one of instinctive decency, genuine principle, and no small amount of courage. It was also the action dictated by her department’s use-of-force policy, the first page of which specifies that it is “the responsibility of law enforcement to take steps possible to prevent or stop the illegal or inappropriate use of force by other officers.”

In his report on the case, Judge Donohue acknowledged that Tasca acted in compliance with the use-of-force policy – but he dismissed that fact on the preposterous grounds that “no evidence was presented to establish that Officer Tasca even knew about the document.”

Only an uncommonly inventive sophist would pretend that the important question is whether Tasca was aware of the document stating the policy, rather than whether her actions were in accord with that policy.

Earlier in the same month, Tasca had prompted criticism for failing to rush to the aid of her partner, Officer Jay Fowler, during a brief confrontation with a tiny, drunken woman at a hospital. The woman, who was not a criminal suspect, was taken to the hospital for medical attention. She decided to leave, and when Fowler – who had already surrendered custody to the hospital – tried to stop her, the young woman “flailed” her arms, inflicting a small scratch on one of Fowler’s hands that tore open an old scab.

As a result of this “altercation” with a woman whom he outweighed by about 100 pounds, Fowler spent a week on paid medical leave, according to Donohue’s report.

“Nobody had said anything to me about the earlier case until after the incident with the Ridgefield officers,” Tasca pointed out to me. Her refusal to gang-tackle a tiny, confused woman in a hospital, coupled with her active intervention to stop a criminal assault on an unarmed, mentally unbalanced man who was not a criminal suspect, supposedly established a “pattern” of behavior that made Tasca a danger to her fellow officers.

After being put on suspension, Tasca was subjected to a psychological evaluation by Dr. Matthew Geller, a psychiatrist who does contact work for New Jersey law enforcement agencies. Geller’s assessment reads like something compiled by a State-employed psychiatrist in the Brezhnev-era Soviet psihuska. Geller claims that Tasca suffers from something called a “mixed personality disorder,” displaying “a personality type characterized by a long-standing pattern of grandiose self-importance and exaggerated sense of talent and achievement.”

This purported dysfunction, once again, wasn’t noticed until after Tasca displayed the character and integrity to take the morally appropriate action – one dictated by the official guidelines of her department – in defiance of pressure from her peers and superiors to conform.

Tasca, an openly gay female police officer, believes that at least some of the problems she’s experienced are the product of a cultural clash with what she describes as “the Old Boys Club.” Judge Donohue’s report mentions two instances in which she was criticized by for not extending what is euphemistically called “professional courtesy” by writing traffic citations against another officer.

Despite such frictions, Tasca’s job appeared secure – until the moment she behaved like a peace officer, rather than a law enforcer, and crossed the “Blue Line” by coming to the defense of Kyle Sharp.

Fidelity to the tribal interests of the punitive priesthood will cover a multitude of crimes, but taking the side of a Mundane being attacked by a member of the Brotherhood is an unpardonable offense.

Dum spiro, pugno!

Content retrieved from: http://freedominourtime.blogspot.com/2012/09/how-to-kill-law-enforcement-career-case.html.